Next month, Rizzoli publish Making It Up As We Go Along – a must-have visual archive celebrating the 20-year visual history of Dazed & Confused magazine, edited by Jefferson Hack and Jo-Ann Furniss.

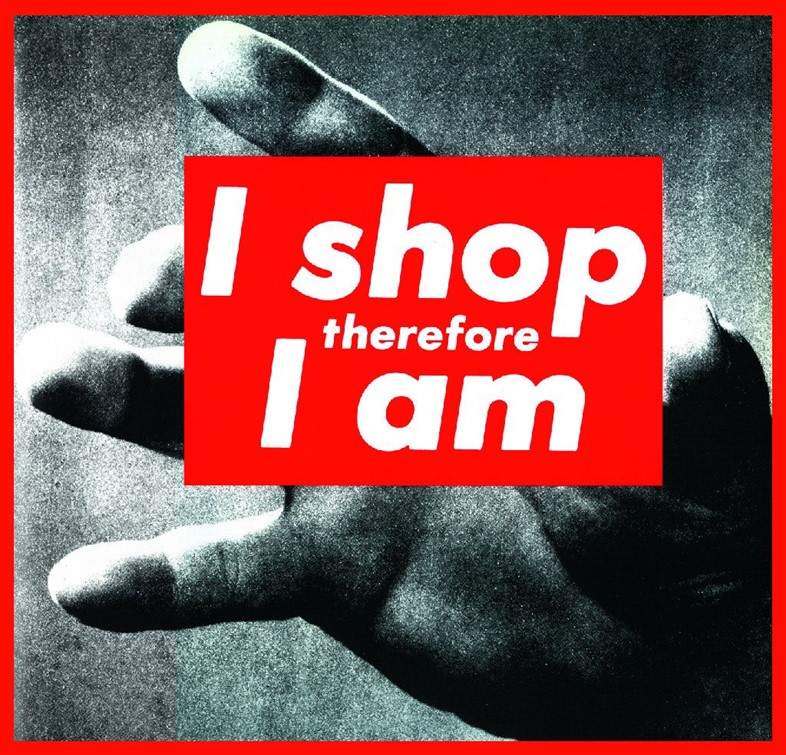

Next month, Rizzoli publish Making It Up As We Go Along – a must-have visual archive celebrating the 20-year visual history of Dazed & Confused magazine, edited by Jefferson Hack and Jo-Ann Furniss. Unsurprisingly, it’s a veritable smorgasbord of stimuli featuring iconic, game-changing work from some of the world’s greatest photographers, stylists and artists. John-Paul Pryor is one of the additional editors who worked on the forthcoming publication, sourcing interviews with some of the in-house movers and shakers that defined the early years of the magazine, and some of those contributors whose specially commissioned works helped to push the form forward in unique and boundary-defying ways. One such artist was Barbara Kruger, who designed a limited-edition cover for The Freedom Issue and took over the inside pages with an intervention that wittily turned the culture of the style magazine firmly upon its head. In the first of a series of in-depth interviews previewing the publication of the book, AnOther presents an interview with the legendary image-maker – whose work has become an internationally recognised feminist touchstone in art history – in which she talks candidly about her process, the power of words and the place in her heart that will always be reserved for Dazed & Confused magazine.

Damien Hirst once remarked in the pages of Dazed & Confused that art and advertising share the same language – is that something you have also sought to explore over the years?

Well, I should say, I’ve never worked in advertising – my experience was as an editorial designer for magazines – but you could say, in the bigger picture, that magazines are vehicles for colour advertising. I think one of the things that art shares with what Damien Hirst would call advertising is that all art – especially poetry, for instance, or visual art – shares an economy with an advertising practice. It is a condensation of thoughts or feelings or moments, and that commentary is an encapsulation of what living might be or feel like. In the long run, my work really came out of my experience of doing serial page designing – it’s not about advertising per se.

What is interesting about employing that economy in art?

One thing I learned working at magazines was that if you couldn’t get people to look at a page or a cover, then you were fired. It was all about how you create arresting works, and by arresting I mean stop people, even for a nano-second. These days, short sentences and phrases are in many ways more vital than ever. The internet means we all have attention spans of kiddies riveted by mouse-like movements. The reason why bookstores are going out of business in The States is that people just can’t focus on longer narratives now – even narrative film is in crisis in many ways, unless it’s an adventure film. Things that require a short attention span are things that I’ve always been comfortable with because I have a short attention span, but my video work and my immersive work all demands a bit more time from the viewer. The videos and the more installations are really conflations of images and much longer texts – they’re scripts.

Where do you think the printed form is going, and is it still a more powerful way to disseminate art than the digital form?

Well, magazines are a powerful way of distributing pictures and words, of course, but we’re in a kind of crisis with the internet – it’s changed the whole trajectory. That doesn’t mean print doesn’t continue on a certain level. I do think people read totally differently online, though. For example, I have been sitting here reading a hard copy of the New York Times. And when I read a hard copy of a newspaper, I tend to read it very differently to how I would online. I tend to read a hard copy of the New York Times every day, and I read the LA Times and The Guardian and The Independent online. I think you read much more rigorously when you have a hard copy, you really do, because the distraction level is lessened – you’re forced to stay with narrative of the story and the story is more explicit, you stay with it. I don’t know… I think that magazines will survive this moment better than newspapers. I remember years ago, when I was at Condé Nast people were saying television would destroy the magazine market.

I think what’s really interesting is the question of where it goes next. How the language of advertising will still be channelled into our consciousness and define us. It could get quite William Gibson, even more subliminal…

I think that’s already there on a certain level. I don’t think it’s subliminal so much though – it doesn’t have to be anymore. As subjects, the readers and lookers are far more passive than they used to be, so it can be forthright and people will just do it. I think the big challenge is whether it’s possible for young people today, or even older people, to experience the world without looking through a lens or looking at a screen.

You have made some quite profound statements with your work over the years, not least in your Human Rights cover for Dazed. Do you believe art can make a difference in society?

I think things change incrementally, and I think art – whether it’s visual art, or music, or movies or any kind of cultural production is in some way a kind of commentary, what it means to be alive, about what it means to live another day, to take another breath. Not literally so, but any kind of notion of an examined life – as such to consider these moments and maybe promote the kind of doubt or questioning, it objectifies our experience on a certain level. So just in doing that, just in creating commentary as opposed to just being full on in the moment, proposes a kind of change or consideration… I think of things changing very incrementally, you know.

Is that what your longer scripts are about, and specifically your pages in Dazed– identity and what it means to be alive?

You know, I write a lot of scripts for my videos, and I listen to the way people speak. I’ve always been very tied to language. I always see my work as coming out of my experience in magazines, so coming back to the form and looking at the mechanisms at work when you look at a page or turn a page was thrilling, especially because it was Dazed. I remember when the magazine first came out – there was no equivalent in America and there probably still isn’t. Dazed added a whole different edge – it contemporised the magazine form to some degree, and that was something that could only have happened in London at that time. In many ways, the work I produced in Dazed is just a commentary about how certain cultures think and see, and like to be seen. I think what they foreground is my continued use of direct address and the use of humour in my work, because laughter is an important device that isn’t owned by either the left or the right... It can be sort of emancipatory.”

Making It Up As We Go Along, by Jefferson Hack and Jo-Ann Furniss, is published in October 2011 by Rizzoli.