15 vintage prints by French writer and photographer Hervé Guibert have gone on display in Vienna, revealing something innately personal

Sex and death make fascinating partners. Freud’s fundamental human drives Eros and Thanatos are both equally present in the photography and writing of Hervé Guibert, who is quite possibly the most interesting artist exploring desire to have been forgotten in the past 30 years – and the subject of an exciting new exhibition at Felix Gaudlitz in Vienna.

Guibert did not restrict himself to one medium. Originally an actor and director, he was a prolific photographer, the first photographic columnist at Le Monde, as well as a novelist, penning more than 25 books over the course of his career. His diaristic book À l'ami qui ne m'a pas sauvé la vie (To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life), which was recently translated and published by Semiotext(e), transformed France’s attitude to AIDS. This fictionalised portrait of Guibert’s theorist Michel Foucault was also a reflection of the artist’s own experience of the disease that ultimately led to his death in 1991, aged just 35. His relationship to Aids was complicated, as he wrote, “I was discovering something sleek and dazzling in its hideousness.” Guibert even created a film of himself at the end of his life, which was broadcast on French television in 1992.

He was as talented at making friends as he was making art, including iconic actresses Gina Lollobrigida and Isabelle Adjani as his confidants. Looking at his self-portraits, all ringlets and come-to-bed eyes, he was more than aware of his beauty, which many noted was combined with a Machavellian temperament. After he rejected Roland Barthes, the writer wrote a hurt letter to Guibert, who later published it. To the Friend also posthumously outed Foucault as gay.

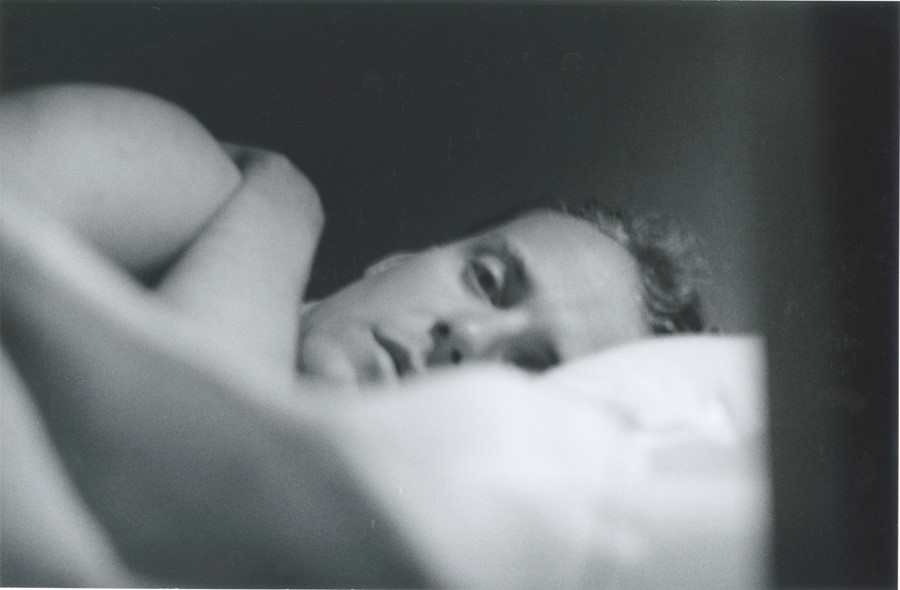

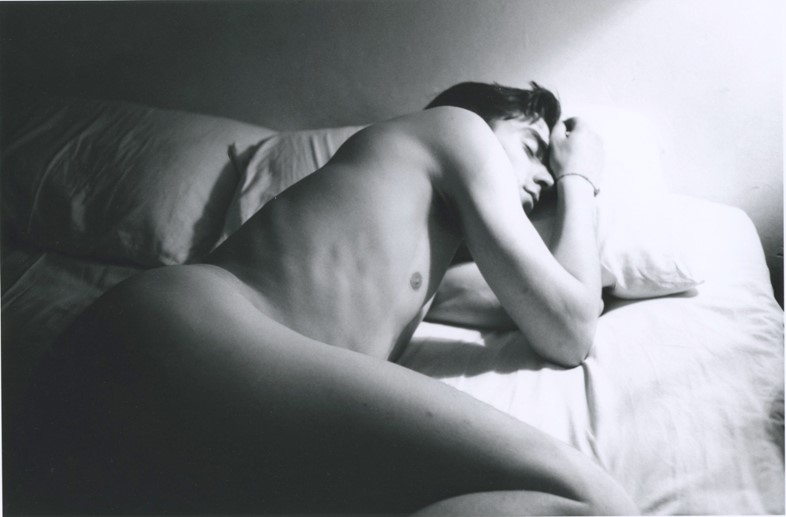

The longest partner and collaborator in Guibert’s life was photographer Hans Georg Berger, who was equally a subject of his work. Bent over a daybed in Elba, opening curtains half dress at the Villa Medici, where Guibert had a residency, intimacy is something that emerges throughout Guibert’s black and white photographs, which reveal something innately personal.

Somehow Guibert is an amalgam of many of the great queer artists of the twentieth century. His images echo the sensuality and darker edges of Peter Hujar, his documents of the experience of Aids are an interesting foil to activist-artist David Wojnarowicz, his writing draws on the rebellious, boundary-breaking representation of homosexuality of Jean Genet, while he himself had some of the public focus and poetic inclinations of Derek Jarman. He was all these artists combined, but also his own entity. His writing was a precursor to the very contemporary genre of autofiction, as he once wrote “my lovers and my friends are my characters, it’s my fictional coherence.” His novel Crazy for Vincent, for example, is a document of erotic obsession and love.

The photographs on show now at Felix Gaudlitz in Vienna – as part of the exhibition entitled Hervé Guibert ... of lovers, time, and death – and soon brought together in a new book, are filled with shadows. In these images, we often look at the back of the protagonist, over their shoulder, onto their naked bodies. The gaze that meets the camera most is the artist’s own, daring us to look back.

Hervé Guibert ... of lovers, time, and death is at Felix Gaudlitz, Vienna until 28 November 2020. The accompanying book is published by saxpublishers.