A new exhibition at Alison Jacques Gallery, London, showcases Parks’ photographs of the boxing champion, taken during a controversial time in Ali’s life

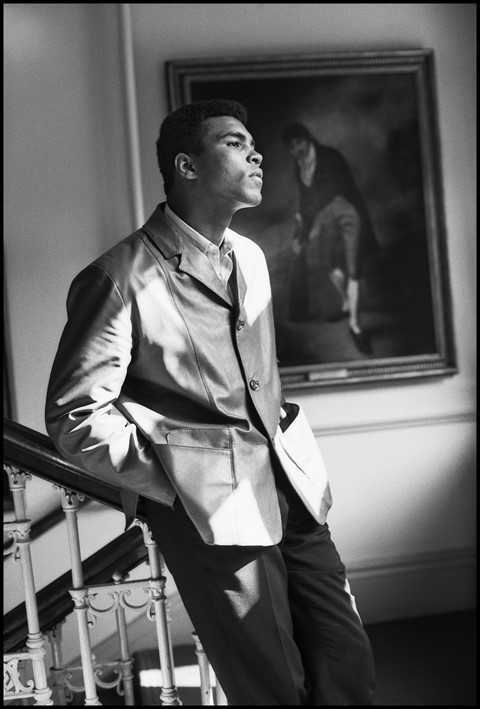

“A revealing and personal encounter between a famous photographer-author and Muhammad Ali,” wrote Life magazine in 1966, introducing Gordon Parks’ profile of the boxing champion. By then, Parks had been at Life for over a decade – he was the first Black image-maker on the magazine’s staff – and was an established photographer, known for also writing the features alongside his photo stories. At the same time, Ali had gained international prominence not only for his prodigious boxing talent, but his recent conversion to Islam. “I felt free to tell him quite directly that I had come to Miami to see whether he was really as obnoxious as people were making him out to be,” said Parks at the time. Parks’ profile of Ali was titled The Redemption of the Champion, and led to a change in public opinion in favour of Ali, as well as an enduring friendship between the two men.

A new exhibition at Alison Jacques Gallery, London, presents a selection of Parks’ photographs of Ali, “intimate and nuanced portrait of the legendary athlete and human rights advocate”, according to the gallery. Entitled Gordon Parks: Part Two, the show follows Part One, staged in July, which focused on two of Parks’ earlier series for Life: Segregation in the South (1956) and Black Muslims (1963).

For the latter report, Parks spent months with core members of Nation of Islam, the African American movement that Ali aligned himself with for a number of years. “In fulfilling my professional and artistic ambitions in the White Man’s world, I had had to become completely involved in it,” Parks wrote in the accompanying article, reckoning with the movement on a personal and public level. “At the beginning of my career I missed the soft, easy laughter of Harlem and the security of Black friends around me … Many times I wondered whether my achievement was worth the loneliness I experienced, but now I realise the price was small. This same experience has taught me that there is nothing ignoble about a Black man climbing from the troubled darkness on a white man’s ladder, providing he doesn’t forsake the others who, subsequently, must escape that same darkness.” A prolific photographer, filmmaker, writer, poet, painter and composer, Parks addressed racial and social injustices throughout his career.

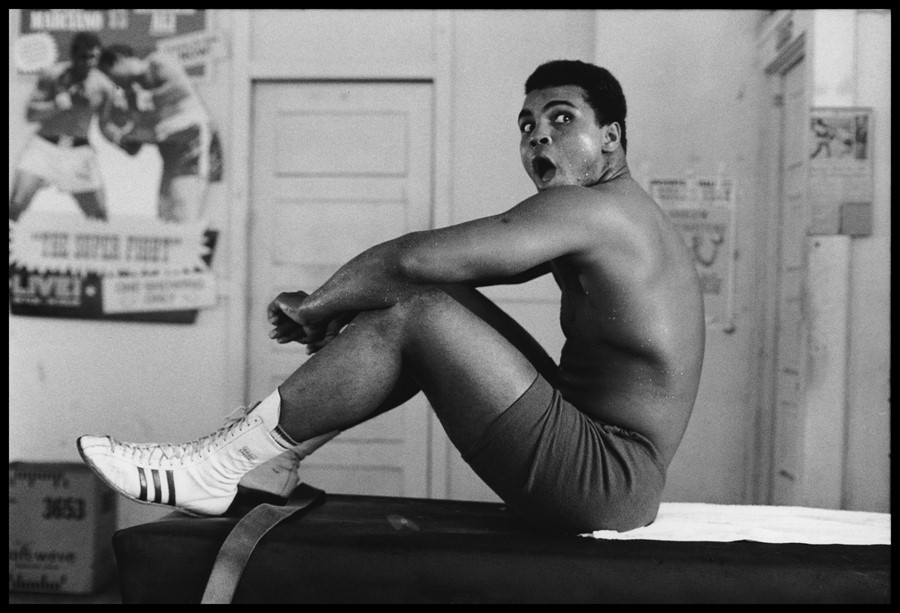

Many of the photographs in Gordon Parks: Part Two are unpublished and have not been previously exhibited in the UK, and come from both the 1966 Life story and a later one published in 1970. Parks captured an unseen side of Ali when he photographed him: the boxer is seen fresh from the ring after a fight; during quieter moments of contemplation; in the middle of training; engaging with fans; and about to eat with family. For an athlete with a complex reputation attached to him, Parks’ warm, intricate and insightful profile marked a significant moment. Early on in his report, Parks wrote: “At that point I began to feel a certain sympathy for him … Muhammad was a gifted Black champion and I wanted him to be a hero, but he wasn’t making it. I also felt, however, that he could not possibly be quite so bad as he was made out to be in the press.”

By the end of a lengthy and revealing profile, Parks was hopeful: “For, at last, he seemed fully aware of the kind of behaviour that brings respect. Already a brilliant fighter, there was hope now that he might become a champion everyone could look up to,” he wrote, with a warmth that hints at the long friendship the two would share. “If only those, back where he was born, extended their patience they would help buoy that hope. From where I had watched and listened, it all seemed so worthwhile.”

Gordon Parks: Part Two is at Alison Jacques Gallery, London, until October 1, 2020.