“If I hadn’t been sick in bed doing all those drugs, I probably wouldn’t have come up with the idea,” Sandro Miller tells AnOther. It was in 2011, when he was in hospital recovering from stage-four cancer, that the veteran photographer decided to embark on a project that most others would have found daunting, to say the least. Having been inspired throughout his life by pioneers of the art like Irving Penn, Horst P Horst, and Diane Arbus, Miller felt compelled to pay tribute to them by recreating some of their most seminal photographs. Initially, actors like Robert De Niro and Willem Dafoe came to mind, and the idea was to use numerous ones. Ultimately, though, Miller settled on his friend and ‘muse’ John Malkovich as his sole subject. “I had already been working with Malkovich for 14, 15 years,” he recalled. “[We] had this beautiful relationship and trust for each other … It was the right decision, as I don’t believe there [was] any other actor who could have given their whole heart and soul the way Malkovich gave them up to me.”

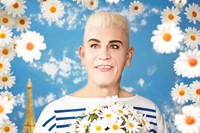

Over a five-year period, Malkovich posed for Miller as Marilyn Monroe, Salvador Dalí and Winston Churchill, among other storied figures, as well as unknown ones like Arbus’ little toy hand grenade-toting boy and Ronald Fisher, a beekeeper snapped by Richard Avedon. Since 2014, photographs from the project have travelled to galleries and museums the world over, and now, in their entirety, are the subject of a major forthcoming book, Malkovich Malkovich Malkovich: Homage to Photographic Masters.

In two separate interviews with AnOther, Miller and Malkovich discussed the making of the photographs and their feelings about them today, as well as their working relationship.

Joobin Bekhrad: Sandro, how was your first-ever meeting with John?

Sandro Miller: When I first met John, I didn’t know what to expect. He was coming off Con Air as Cyrus the Virus, and if you weren’t a bit intimidated by his character in that film you were numb. I mean, he was a fucking monster. I could only think that I had better be ready for him, be prepared, and not have him standing around too long … [The reason it went well] was because [we] were two artists who truly respected each other’s work.

JB: John, what did you think about the project when Sandro first mentioned it to you?

John Malkovich: I thought it was a good idea. I thought it would be super challenging and especially, if nothing else, super challenging for him and also expensive organisationally, because [he] had to repeat all that stuff to create all those things again …

I remember always hearing [the phrase] “the camera doesn’t lie”, and at least by the time I’d started working in the movies, I would often respond, “That’s what it’s for.” And so, that kind of play between those two sort of fixed points, those ideas or concepts, was something that interested me a great deal. On a certain level it’s also kind of scary how easy a deepfake is, and that’s something that I think will become more and more prevalent in society … You can kind of make people believe anything, especially if they don’t look in great detail. Like the [photograph] of [me as] Einstein. Most people look at it, at least in my experience, and really don’t see the difference. It’s amazing what you can fake in this world [laughs], and without Photoshop. That sort of old-school F for Fake.

JB: Did you at all find it odd that Sandro wanted to use you as his one and only subject?

JM: Well, yes and no, in that if you have any degree of self-awareness or even any kind of modesty – I don’t mean a profound modesty, just a normal human modesty – one wonders why anyone is interested in them or working with them or anything of the sort. At least I do. I think that’s normal. But I also don’t obsess about it. People want what they want, they have the projects they like to do. You know [laughs], obviously most of them don’t involve me, and I’m sure they’re all the better for that. And some do. So that’s how I look at it.

JB: You’re very modest.

JM: No, I don’t think so. I think I just understand that, you know, when you’re a person in the public eye, there are a lot of projections – mostly projections about what you are, about what you’re not, about what you could be, about what you should be, about what you shouldn’t be, et cetera, et cetera. And I kind of believe that I can’t control [others], and I don’t attempt to. So if someone says, “You should play Bette Davis,” I seem an unlikely choice, to me. But what do I know?

JB: What was shooting with Sandro like?

JM: Sandro is very, very in charge and in control about what he wants, and clear. So if you don’t want to do that, then don’t work with him … Of course, you can have people who are so controlling that they’re incredibly irritating, but that’s not the case with Sandro. He’s very accepting and responsive to what’s given out, but these things are so particular and so specific that you either reach, sort of, max speed with [them], or you don’t.

I worked a lot with Randy Wilder, the make-up artist. Sandro would explain what he needed to me. I would work a lot with Randy and Leslie the costume [designer] and get everything, all this sort of, our end of the visual components and visual adaptations or mirages or illusions to what extent we were capable … So you go through with make-up and hair and you say, “OK, we’ll try and emphasise this and de-emphasise this and we do this and we do that.” And that was only with make-up. Sometimes [we used] tape, like old Hollywood used to use to make people appear younger ...

[The photographs] that [were] really hard to do were [ones] like, say, David Bailey’s photograph of Mick Jagger. I don’t look like Mick Jagger at all and Mick, I think, was 19 when that photo was taken and I was 62, and that you can’t do anything about. And we didn’t really, beyond sort of little make-up tricks as opposed to photographic tricks. We didn’t really try to.

JB: How would John get into character for the photographs?

SM: I would watch John as he would [get] his hair and make-up and wardrobe [done] for anywhere between three and five hours per character … He was no longer John Malkovich; he was only referred to as ‘Che’, or ‘Alfred’, or ‘Winston’ … Once on set, John would be so deep into his character that the crew would watch in total amazement. I would become the original photographer and John would be the sitter of that photographer for that moment.

We often had great laughs with John during the shooting of different characters. Watching John transform himself into a nude Marilyn Monroe was astonishing and a bit bizarre. After all, John was a 60-year-old man when we did the Marilyn photographs and Marilyn was a 30-something bombshell sex symbol. John worked on that character so fucking hard to become Marilyn. He went into this deep trance-like extension of himself … It took John about five minutes to break character, and I remember I just kept shooting while he was transforming back to John Malkovich. Those were some of the best photographs I have ever taken.

JB: Did you ever find yourself comparing your looks to those of some of the figures you portrayed? Were there ever any moments of insecurity in this respect?

JM: I’m just not of that generation … I don’t compare myself to Gary Cooper, because Gary Cooper was exceptionally pretty and I’m not. And anyway, what difference would it make? You are who you are. Now, you can do RuPaul if you want – and there’s a lot of RuPaul in this. But I don’t feel the need to escape from myself particularly, and anyway, even if I did, that’s what I do all day at work. I’ve done it for more than 40 years, so I’ve been somebody else most of my life.

JB: Were you uncomfortable during any of the sessions?

JM: No. Although it’s spectacularly impermissible now, when I grew up, that’s why you became an actor. I mean, to do things that weren’t you and visit worlds you didn’t know, that you’d never visited and maybe would never visit again, and kind of experience, through [a] sort of character osmosis, points of view that you really may not have had before. You know, now that’s sort of more or less verboten.

JB: How satisfying was this project to you as an artist?

SM: Artistically this project gave me everything a photographer could ask for. I put so much of myself into the making of every image to perfection that I made myself sick from the mind-bending difficulties [involved] … [But] I think I am most happy knowing this project has now been travelling around the world for the last five years and will continue for many years to come.

JM: I don’t know what satisfaction [is]. It seems to me such an odd thing [laughs] … because one is onto the next and the next is the next project, the next situation, the next bit of work is absolutely exploding with possibilities for failure. And so I just move on to that. I can only feel – totally un-neurotically, by the way – I can only feel, “I should have done that” … “Sandro should have said, ‘one more’ or ‘no’.” Satisfaction is just kind of an alien concept to me in work. And I don’t think I’m that strange, either. I think it is for a lot of people – and I think it should be. Because you have to be restless.

[But] I’m really glad we did [this]. I think it was a very worthy project. We certainly didn’t do it for money, et cetera. It was a kind of experiment, and I think a fascinating one.

Malkovich Malkovich Malkovich: Homage to Photographic Masters by Sandro Miller is published by Skira. Images from this book are being displayed as part of a touring exhibition, which opens next at Maggazino delle idee, Trieste, Italy October 30, 2020–February 7, 2021.