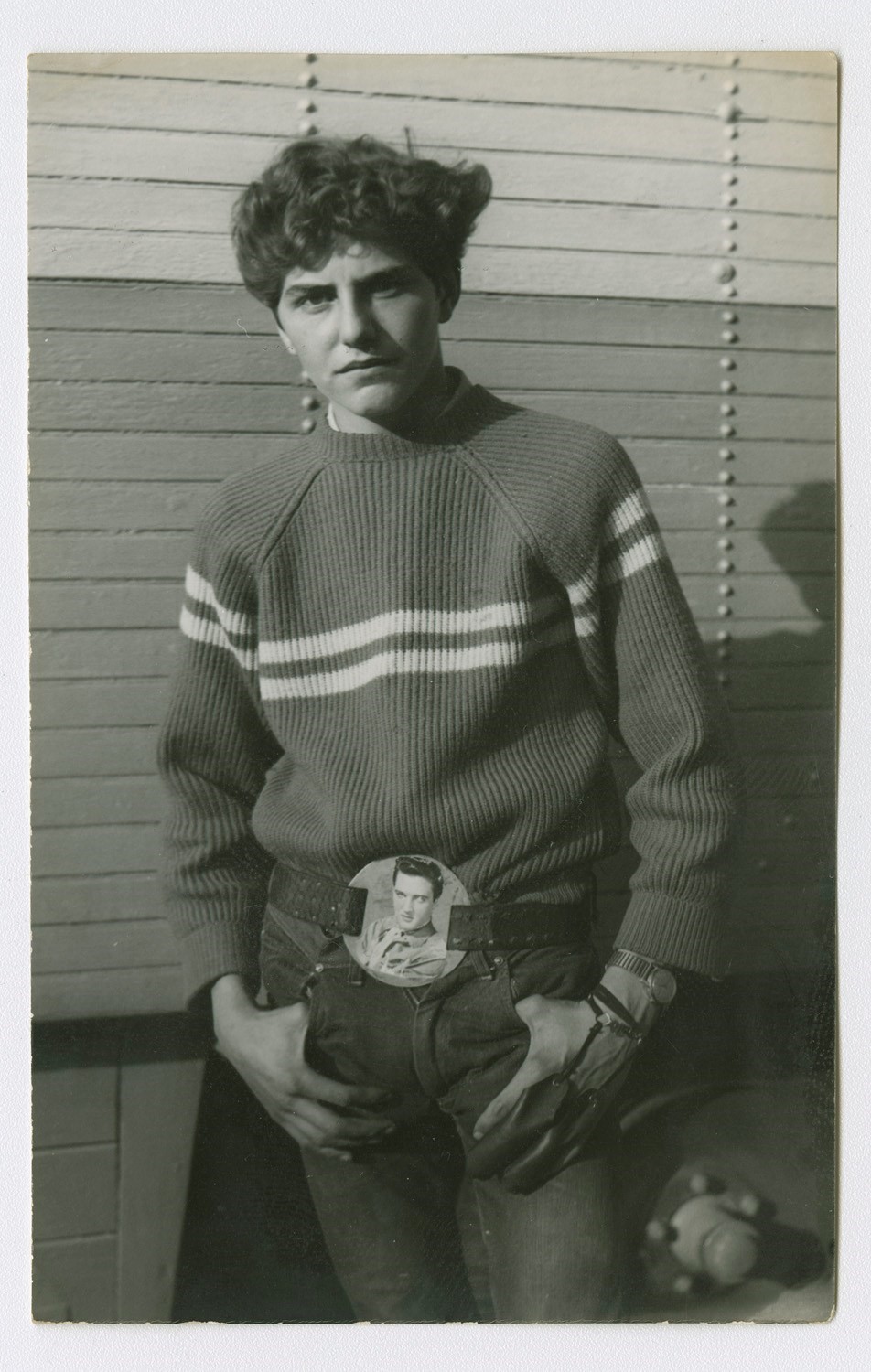

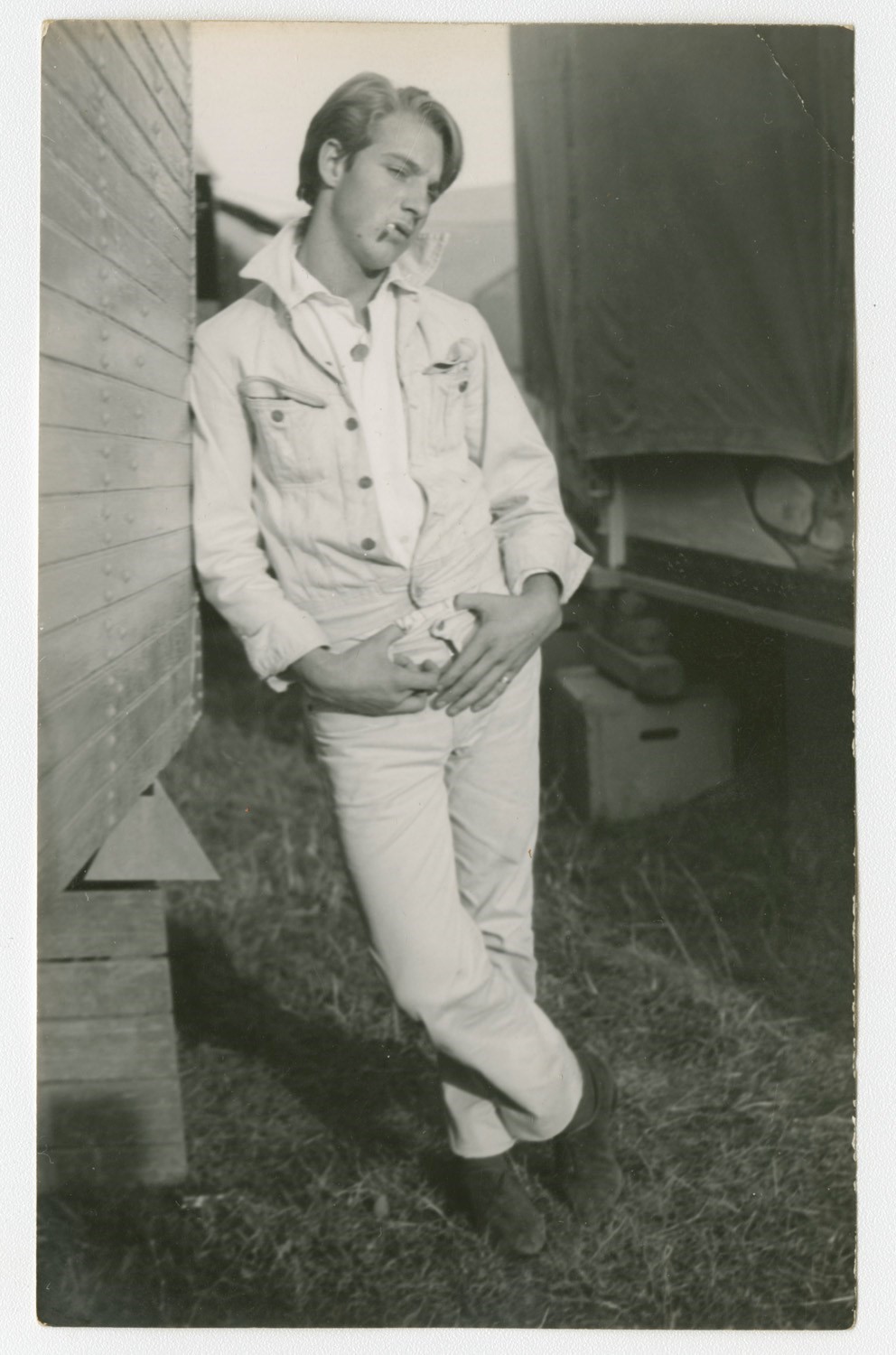

Though they were taken between the late 1950s and the mid-1970s, the images of Swiss photographer Karlheinz Weinberger have lost none of their power. Predominantly focusing on men, in a way that is at once immediate and intimate, his pictures capture outsiders; those living life on the margins – from the “Halbstarke”, a group of Swiss “rebels” active in the late 1950s and early 1960s to construction workers, street vendors, bicycle messengers, among others. A new book published by The Song Cave brings together 200 such photographic prints, which have never been published before and were only rediscovered in 2017.

Entitled Karlheinz Weinberger: Photographs: Alone & Together, the publication brings together Weinberger’s images of the Halbstarke and his portraits of men, who appear fully clothed, fully nude and in various states between. Voyeuristic, yes, but profoundly artistic, too, these images are charged with an electric, erotic and enduring power. The artist Collier Schorr is no stranger to this power and has written an introduction to this book, which is excerpted exclusively, in part, below. Here, she unpacks the unique properties of Weinberger’s oeuvre, ruminates on his relationship with – and depiction of – his subjects and recalls the brief period in which she owned one of his (more taboo) works.

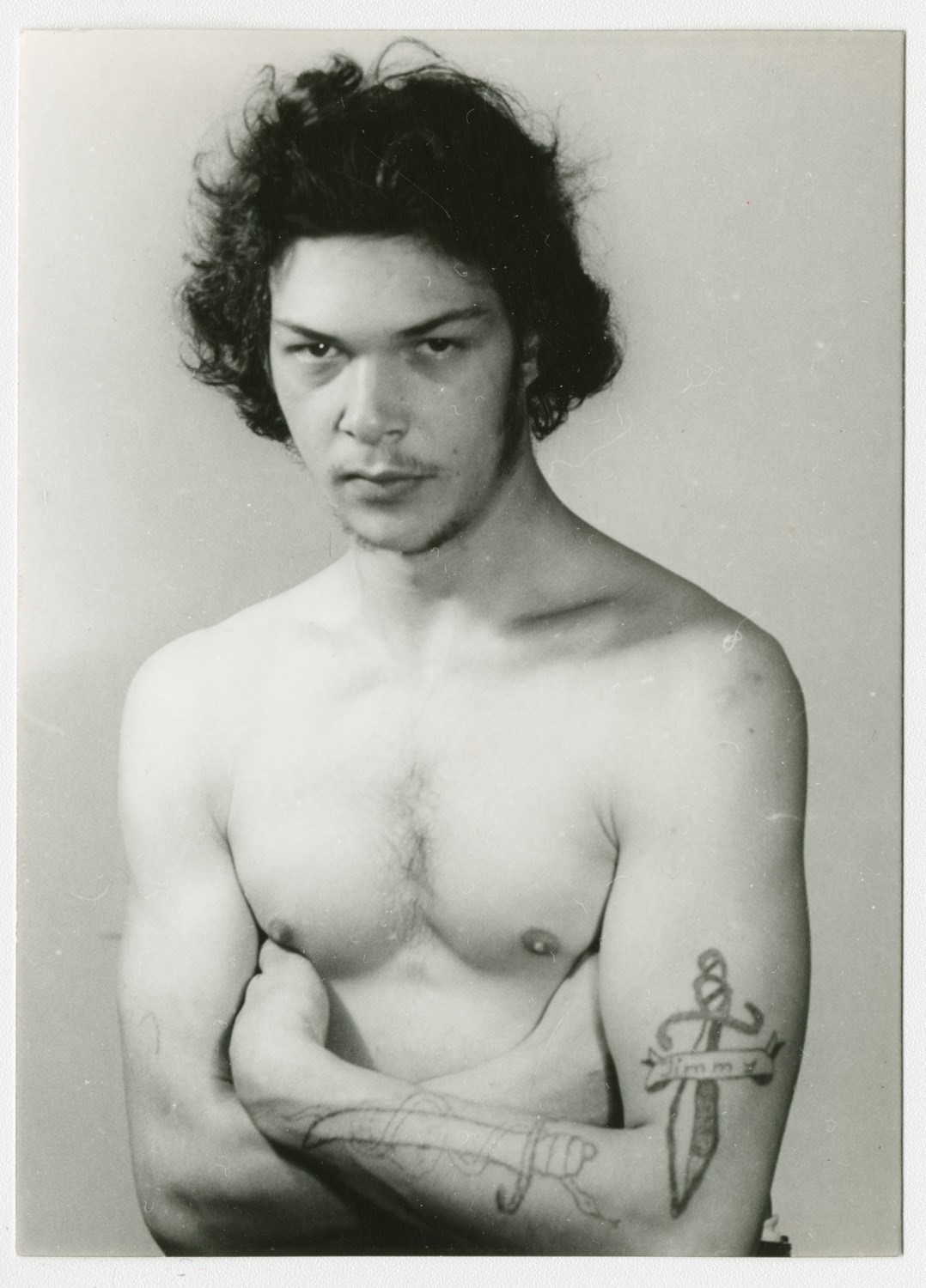

I hate to talk about love in photography, because as a practitioner who has been in love I know this kind of love fades like the writing on a candy heart left in one’s pocket. The I love you disintegrates. It seems particularly male, of the moment, in penetration and ownership no matter how feminine and maternal I might feel. Loving has a use value. Keeping a subject in front of you. A camera is a dick. It is not a vagina, though in another essay I could argue that it’s a tunnel the subject is compelled to enter. Truthfully, it’s more a thing that punctures the ego of the person in front of it. Stabs them in their sudden need to be adored. What Weinberger did, however, was to not move on so fast. His camera stroked the boys it commandeered. It must have, because they seemed to stay around. Having dressed up and done their hair and laced their crotches, Weinberger was their screaming chorus of girls. The fanbase. In his apartment the lights made a stage, the stage of white boards supported the performance. I imagine the photographer’s elbows worked the camera while young hips swayed to the rhythm.

“A camera is a dick. It is not a vagina, though in another essay I could argue that it’s a tunnel the subject is compelled to enter” – Collier Schorr

Weinberger is best known for his images of the younger rebels. They have been copied in countless fashion shoots, irresistible to stylists. Mostly the studio shots. In looking through the edit in this book, the countryside images, there is a looseness and a nice level of distance. Less static than in the artist’s homemade studio (in the same house where his mother lived), here you clearly feel a life is being lived by faraway minds. Weinberger is not with them, but is in on it. There is a dichotomy between the close-up and the voyeuristic landscapes. A boy perched on the knees of a girl, who could be a boy, because you see such similar jeans. These pictures make me feel wistful. The way the camera celebrates the thing it isn’t. It’s a strength, and it causes a romantic illusion. At one point the boys Larry Clark photographed were his age. They were kind of gross and fucked up. Then he got older and the boys felt younger, chosen for a kind of cuteness, in fact chosen period. And Ryan McGinley was in his pictures looking much the same as the other kids, his friends. Now he is not. Was Weinberger ever young with his subjects? Was he ever just one of them?

“Was Weinberger ever young with his subjects? Was he ever just one of them?” – Collier Schorr

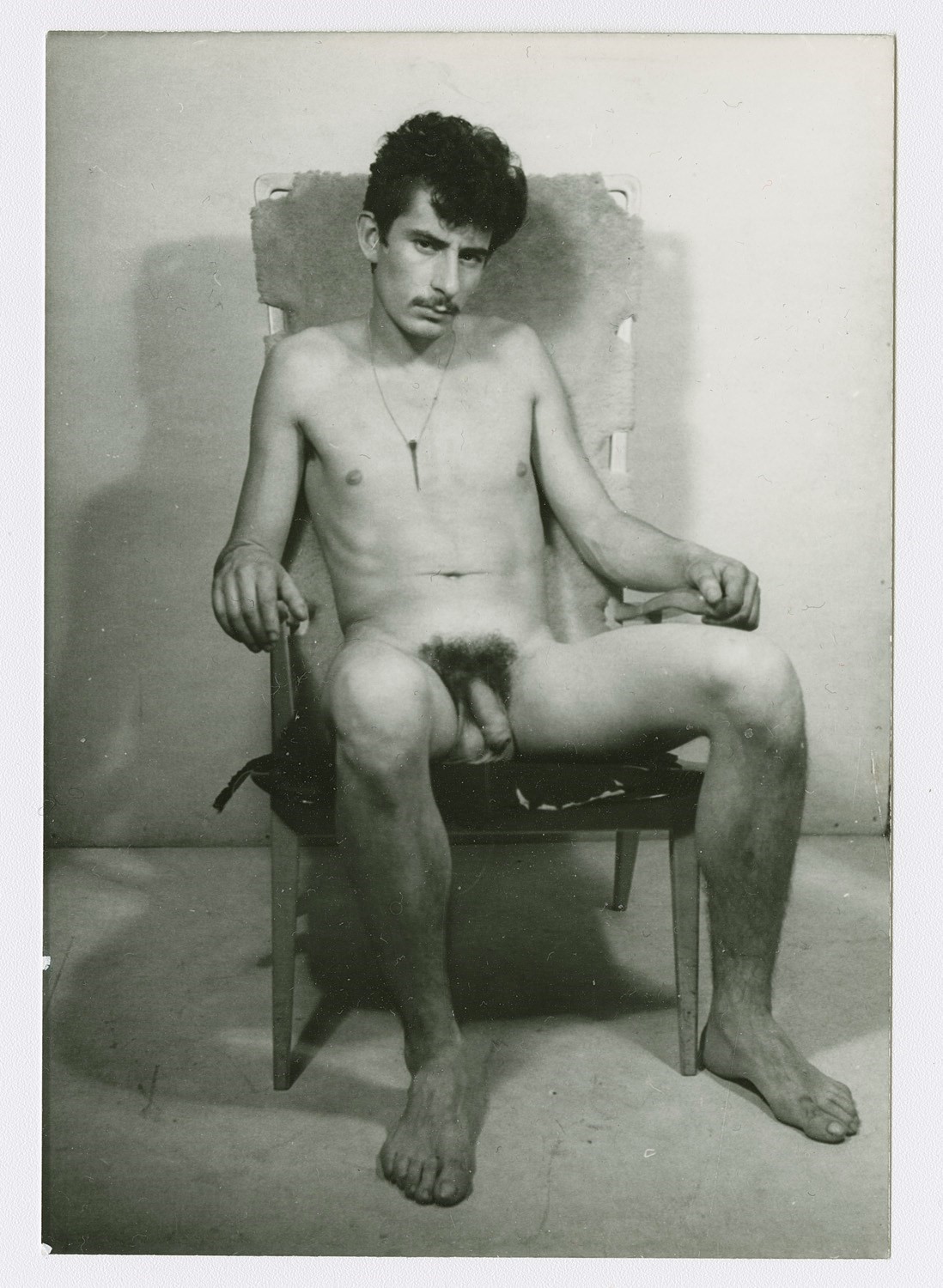

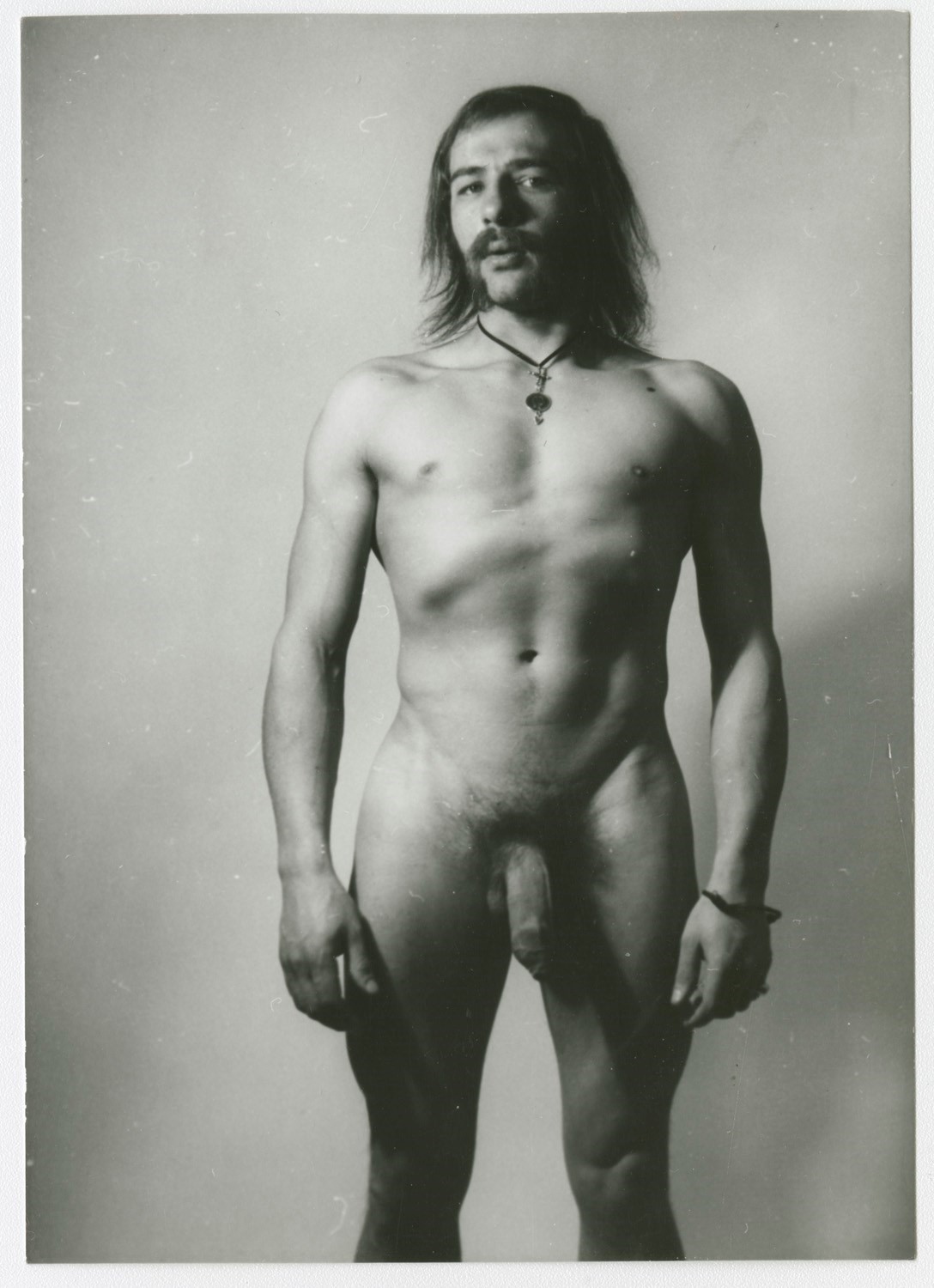

That illusion of the dreamy pal fractures in the second part of the book, a series of recently found prints of nude men and boys. Most of the clothes are gone and most of the “pretty boys” are gone. There is a change of cast. Shot from the 50s to the 70s, these pictures have a catch-as-catch-can feel. The men are a little more real, less pirate fairies with extremely crafted hair. They are in the studio/house, white cardboard flats, and beds, and white-walled corners. I confess I prefer spectacle in a cock photo. I know this about myself. I’m less interested in “collection,” like critic Vince Aletti. So my take on these is prejudiced. I really got to know about cocks from the Moroccan boy penises of Baron Wilhelm von Gloden photos, and the grown-up African American men Robert Mapplethorpe cruised. So, the male versions of the mother and the whore. I want it to be extreme or barely there. Weinberger’s nudes are actually poignant. The flesh is usually small, white. Illusions and expectations are a bit lost. For me, it’s a search but I don’t know the dialogue. The before-and-after that results in these almost shy, tender images. I always found nudes challenging because the skin lacks a contrast. No clothes make no identities. White bodies make blanks (blanc). Perhaps these images are closer to who Weinberger was? They certainly speak to the future compulsions of Bruce Weber, and the contemplations of Jack Pierson. But they also dismantle the fantasy. Photographers are promiscuous and their modern medium with rolls of film means they could make a lot of pictures. Hunt for the one, own the many. Souvenirs – the symbol of experience, and for a photographer, also the proof of being acknowledged. The studio portrait proves the person was there, and that he looked at the photographer. My favourite image is of a young blond man, with almost a gymnast’s short thick body, one knee cocked. His hand is covered by the aluminum globe of a studio light, which feels as open as an orchid.

“Weinberger’s nudes are actually poignant. The flesh is usually small, white. Illusions and expectations are a bit lost” – Collier Schorr

For a few days I owned a Karlheinz Weinberger image of a biker in a Nazi helmet wearing a denim vest. It cost $900. I put it in a show I curated called Overnight to Many Cities. It was mine. Every day I saw this image on the wall, and became more and more anxious. I finally cancelled the purchase. I worried what wanting that image said about me. And what it said about all the fabricated Nazi pictures I had made in Germany. How I had wanted it felt directly connected to how Weinberger might have wanted it. Theatrical danger. Instant character, as Susan Sontag wrote of immediate connections. You look at them and they look at you, and it must commence.

Karlheinz Weinberger: Photographs: Together & Alone is available to purchase from DAP and The Song Cave. Additionally, a selection of photographs from the book are currently on display at Situations Gallery in New York City.