Centropy, Deana Lawson’s largest exhibition to date, opens at Kunsthalle Basel today

When Elena Filipovic first saw Deana Lawson’s proposal for her exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, she thought it might look a bit overcrowded. “I was thinking of a traditional hanging in which artworks have lots of space around them,” explains Filipovic, who has been the director of the Swiss contemporary art institution since 2014. “But Deana came back to me and said that she wanted the figures in her photographs to have the proximity of a family, and above all she thought they needed to be close together for their own ‘protection’.”

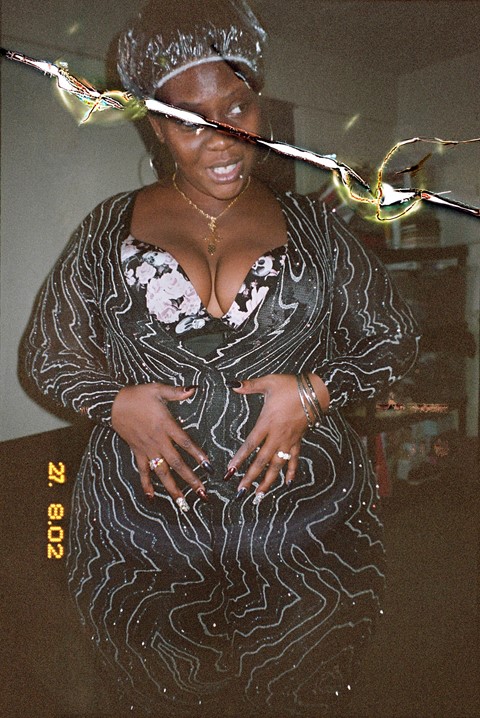

The protagonists of Lawson’s portraits might be strangers, but as the artist once told The New York Times, these “displaced kings and queens of the diaspora” are linked by a shared history of slavery and colonialism. “In Deana’s work she is always thinking about how to exalt and give an image to the black communities that haven’t appeared in official records, or when they did were only shown in stereotypical ways,” says Filipovic. “She takes their vernacular in all its beauty and splendour and puts it on the grand scale of history painting.”

Named after a physics term that refers to the tendency for particles of a system to come together in an organised manner, Centropy is Lawson’s largest exhibition to date and only the second presentation the New York-based artist’s work in Europe. Comprising almost entirely of new pieces, the exhibition offers a window into contemporary black life across four countries, including the USA, Brazil, Jamaica and Ghana. One of Centropy’s most striking portraits, Daenare, was taken in a favela, for example, and depicts a nude pregnant woman with a tracking device fixed around one ankle. Deanare might be seen as a criminal in the eyes of the Brazilian government, but under Lawson’s careful lens her languid pose recalls a number of famous reclining nudes from art history.

Speaking in a conversation with Filipovic during the exhibition preparations, Lawson explained that while her images weren’t necessarily intended to be “corrective”, she nevertheless “knew that there was something so powerful and beautiful that was missing from the canon”. Her works attempt to fill that void, combining real and imagined histories to offer images of regular black folk that are otherwise rarely seen. In another standout image from the show, a man sits wide-legged on a sofa that has seen better days. Wearing a crown and other elaborate jewellery, he is, the image’s title suggests, a chief, but his slightly awkward pose suggests he’s somewhat uncomfortable with this moniker. Taken in the Ashanti region of Ghana, this piece was elaborately staged by Lawson and refers to the region’s gold production as well as to the Ashanti Empire, a history, Lawson points out, that African Americans are rarely taught. “I think we would have a different idea of self if we had a deeper knowledge of these dynasties in Africa,” she told Filipovic.

Although Centropy was planned long before the murder of George Floyd, it’s even more poignant in light of the surge of activism and protest around the world against racism and police brutality that have taken place in the past two weeks. “The show was literally being hung simultaneously with the murder of Floyd and the outrage that has accompanied it, and is now haunted by both,” says Filipovic, who also points out that the show opens in the middle of a global pandemic that has disproportionally affected people of colour both in the US and abroad. As these protests rage on and we see yet more instances of police violence against black and brown bodies, Lawson’s affirmative images of black life offer a powerful reminder of what we’re fighting for.

Deana Lawson: Centropy is at Kunsthalle Basel from June 9 – October 11, 2020.