To celebrate Tate Modern’s Andy Warhol retrospective opening today, Andy Stewart MacKay explores how Pop Art – and Andy Warhol – turned the mainstream queer

Spanning more than three decades, Pop Art first emerged in 1950s London before taking root in France, West Germany, the United States and even the Soviet Union. Radically figurative and popularly accessible, Pop artists were young and controversial. Described in 1962 by critic Max Kozloff as “New Vulgarians” and dismissed by abstract artist Mark Rothko as “Popsicles”, Pop artists rejected metaphysical ‘meaning’ in favour of everyday lived ‘reality’. At a time when the West experienced an acceleration of material excess, Pop artists responded by critically engaging with culture, democracy and identity as affirmed by the individual’s power to consume. If you understood the propagandist language of advertising, you understood Pop Art. To paraphrase René Descartes, “We consume, therefore we are”.

A central dilemma for artists in the postwar period was whether to embrace the reigning ideology of consumerism – as the only model for the production of art – or subvert it. In Andy Warhol’s case he was happy to do both. It’s not for nothing he named his studio The Factory and boldly proclaimed ‘Art is Business’. With canny and performative slights of hand, however, his creative subversions still often elude detection amidst calculated humour and provocation. Postmodern irony was his modus operandi, and it served both to highlight and expose mainstream (un)thinking.

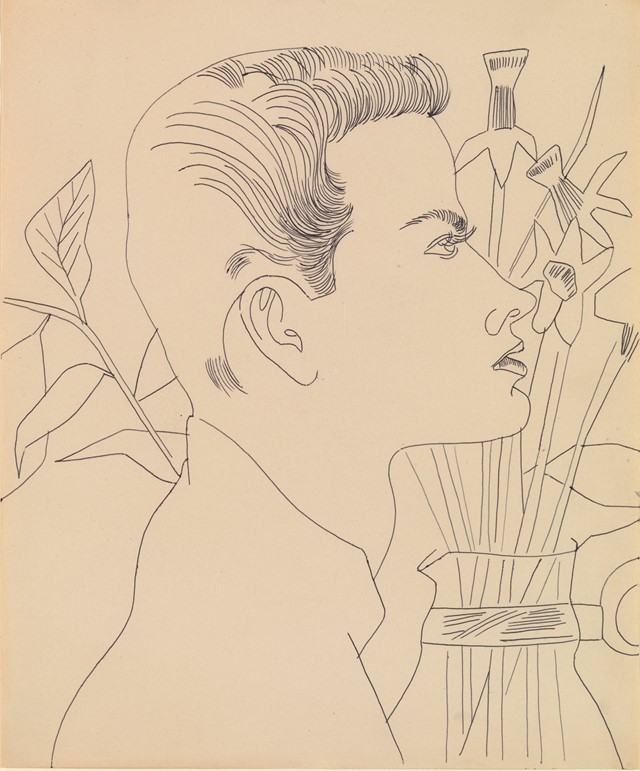

As a young gay man and successful commercial illustrator in 1950s New York, Andrew Warhola – as he then was – quickly learned the queer necessity of subtext and never forgot it. Soon, he and his Pop Art contemporaries were the first ‘fine artists’ to engage in concerted ways with issues of identity, gender and sexuality in strikingly (post)modern ways.

Indebted to the cultural legacies of Dada art and Existentialist philosophy, before the emergence of identity politics Pop artists and their theorists contributed to and reflected 1960s “liberation movements”. In her 1964 essay Notes on Camp, first published in the Partisan Review, cultural critic Susan Sontag famously located and described a new avant-garde queerness that bore striking similarity to other contemporary definitions of Pop Art. In essence, camp is an irreverent attitude; one that shades into the subversive by first resisting, then reclaiming and repurposing, prevailing norms. For Pop artists like Andy Warhol it was precisely this camp sensibility or persona that generated their kitschy images and objects, and made space for reinventing the body itself. At a time when camp was essentially a synonym for gay, Sontag declared ‘being’ and identity as a fluid and liberatory performance.

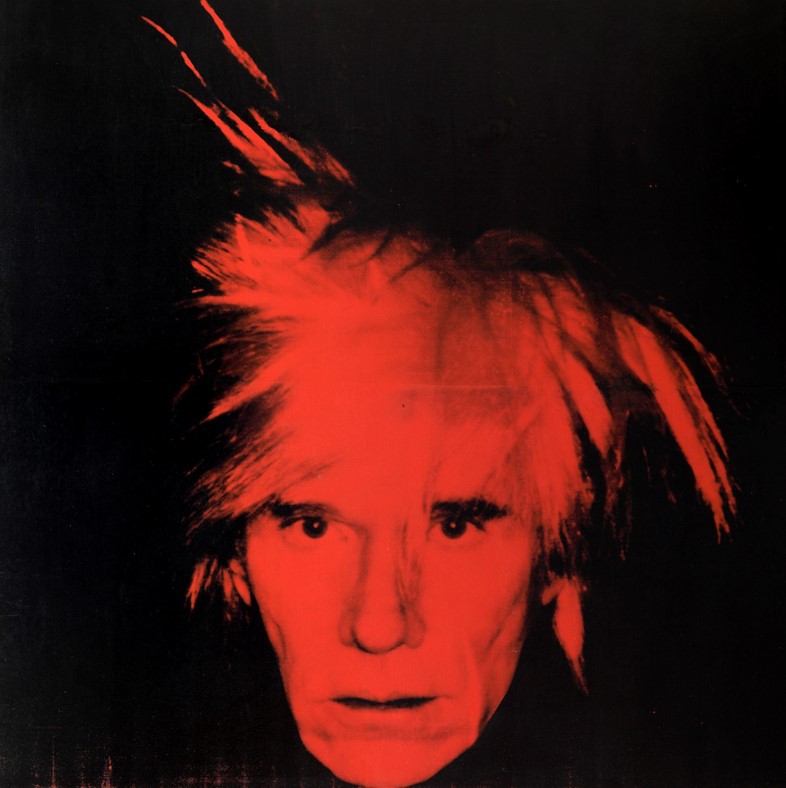

Although posing as disinterested in ‘depth’, Warhol in fact layered his concerns; hiding them in plain sight. Like advertising, the glossy surface of his work appeals to both the city banker and the street queen. And, just as with advertising, under close scrutiny much can be discerned beyond the image surface itself. Warhol’s interest in comic-book hero Superman, for example, employed as a recurring motif both at the start of his career and towards its close, suggests a homoerotic affinity with the alien immigrant who transforms himself in the big city. His ‘punk pop’ period in the 1970s – and his ‘Piss’ paintings in particular – developed his personal, albeit archly detached, interest in sexual subcultures first advanced a decade earlier when he began making pornographic films. Always a media man, in 1985 Warhol ‘performed’ onstage as the first digital artist with his new Commodore Amiga 1000 computer. Consistently alchemising the marginal into the mainstream, he presented the cultural fringe as a prescient vision of contemporary urban life.

Other Pop artists also embodied ‘queer’ in their artistic practices, and many felt more able that Warhol to openly and explicitly challenge everything from art and politics to gender and sexuality. Marisol, Nikki de Saint Phalle, Dorothy Grebenak, Sister Corita Kent, Martha Rosler, Idelle Weber and Rosalyn Drexler each deserve greater and more widespread recognition for their uniquely powerful and compelling bodies of work that broadly explore how to be both an artist and a woman. Similarly (although clearly better known), David Hockney, Ray Johnson, Robert Indiana, Duane Michels, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat creatively explored life on the cultural margins.

Precisely because of its deliberately self-conscious and ironic complexity, Pop Art can be anything to anyone – which is part of its distinctly enduring appeal. Like the best of modern art, it holds up a mirror to its audience. But it shouldn’t be forgotten that within it’s historical, political and cultural context, Pop Art was deeply radical and its legacy profound. Whether or not anyone’s noticed, Pop Art – and Andy Warhol – turned the mainstream queer.

Andy Warhol is at Tate Modern until 6 September, 2020.

Andy Stewart MacKay is the author of The Story of Pop Art (Octopus).