Widely known as Picasso’s muse and lover, a new exhibition at Tate Modern proves that Dora Maar was an exceptional artist and photographer in her own right

When Dora Maar’s relationship with Picasso came to an end, she had a breakdown and became a recluse – or so the narrative goes. But as a major travelling exhibition shows, there is far more to the French-Croatian artist and her work than is commonly shared.

Born Henriette Theodora Markovitch in 1907, Maar met the great Spanish painter in the winter of 1935 and the pair made many portraits of each other during their tumultuous relationship, sometimes working together in her darkroom and his studio. Maar is famously immortalised in Picasso’s Weeping Woman (1937) and she documented the creation of Picasso’s seminal painting, Guernica, that same year.

Although it is true that the break-up contributed to Maar’s breakdown after World War II and she withdrew from artistic circles in the 1950s, Maar continued to make work, focusing her attention on the landscapes around her home, which took the form of abstract paintings (she divided her time between Paris and the south of France); Maar also painted many still lifes. Decades later, in the 1980s, she returned to photography, producing camera-less photographs and tampering with a number of her negatives in creative ways – scratching and painting over them or corroding them with acid.

Despite Maar’s enterprising spirit and commitment to her art, the artist’s work and legacy have never fully been given the attention they deserve, until now – an eponymously titled exhibition opening at Tate Modern in November seeks to set the record straight. Featuring more than 200 works from across Maar’s career, the show follows a recent retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and will travel to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles in 2020 for the final leg of its tour. “Part of the thinking behind the exhibition is to think about Maar as someone who has been mythologised, whose image has been used, particularly in Weeping Woman,” says Emma Lewis, assistant curator at Tate. “But how much do we know about her, how far can we get beneath and beyond that? That’s what the exhibition at Tate Modern will do.”

She produced cutting-edge fashion and beauty photography...

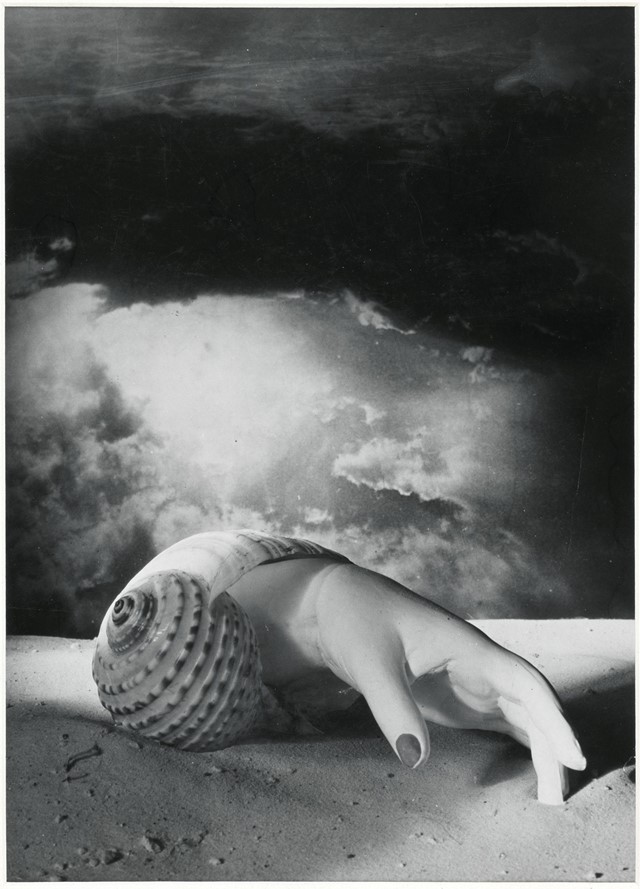

Maar studied painting and decorative arts before turning to photography, and throughout the 1930s worked as a professional photographer, creating highly inventive fashion and nude images, as well as portraits and commissioned photographs for advertising campaigns. One of her most iconic creations is Les années vous guettent (The years lie in wait for you), an image constructed from two negatives that was likely made for an anti-ageing cream. Often using her friends as models, Maar created nude studies of renowned model Assia Granatouroff which, although not entirely unusual for the time, were fairly daring. Images such as Assia, 1934, that were considered slightly risqué at the time, show how women photographers including Maar were not afraid to step into nude photography and erotica.

...and found success in the biggest fashion magazines of the day

Having set up a studio in Paris in 1931 with film set designer Pierre Kéfer, Maar like many other women in the 1930s, took advantage of new professional opportunities in the wake of the development of the illustrated press and advertising. Commercially successful and constantly in demand, Maar worked assiduously for dozens of publications including Excelsior modes, Le Figaro illustré and Rester jeune as well as for beauty companies and fashion houses. Maar’s first fashion commissions for couturier Jacques Heim’s eponymous fashion magazine came early on in her career in 1932 and after World War II she returned to fashion, creating textile designs for the fashion house. Her client list also included Jeanne Lanvin, Elsa Schiaparelli, Jean Patou, Madeleine Vionnet and Chanel.

Politics and activism were integral to her work

Publications provided Maar “with an arena for photographic experimentation, a liminal space in which the interplay and contradictions between fantasy and reality – a duality that fascinated the Surrealists – could be acknowledged and explored,” writes J. Paul Getty Museum associate curator Amanda Maddox in the accompanying catalogue to the exhibition. It was within the pages of these magazines that Maar could “subvert convention,” says Maddox. Maar, who was politically and socially involved with the far-left during the 30s, was one of the few photographers invited into the Surrealists’ inner circle and made portraits of the movement’s most influential figures including André Breton and Paul and Nusch Eluard.

She sought out Surrealism in the streets

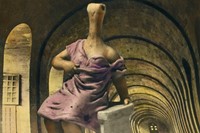

Maar’s eye for the surreal is evident not just in her fashion photographs and advertising work, or even in the off-the-wall photomontages created during her association with the Surrealists in the early 1930s, but also in the social documentary images she took in some of the poorest neighbourhoods in Paris, Barcelona and London around the same time. Like her Surrealist comrades who enjoyed wandering through labyrinthine streets hoping to happen upon fantastical goings-on, Maar too scoured the urban environment opening herself up to whatever magic might come her way. Maar’s paintings made both during and in the decades following her relationship with Picasso, also hint at her love of all things surreal in that they embrace abstraction and depict magical, dreamlike worlds.

Maar and Picasso inspired each other

It is widely accepted that Maar and Picasso had a profound effect on the other but less talked about is the extent of their creative exchange. In an interview with Frances Morris (now director of Tate Modern) in 1990, Maar said that the electric light in Picasso’s political masterpiece Guernica was inspired by one of her paintings, and she also claimed that Picasso’s decision to use black and white for his painting was influenced by photography. It was Picasso who encouraged Maar to take up painting again, which she did in 1936, and Maar directed the artist in using cliché verre, a technique that combines painting or etching and photography. The relationship may have been volatile but there is little doubt each artist saw something in the other that caused creative sparks to fly.

Dora Maar is at Tate Modern from November 20, 2019 – March 15, 2020.