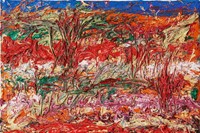

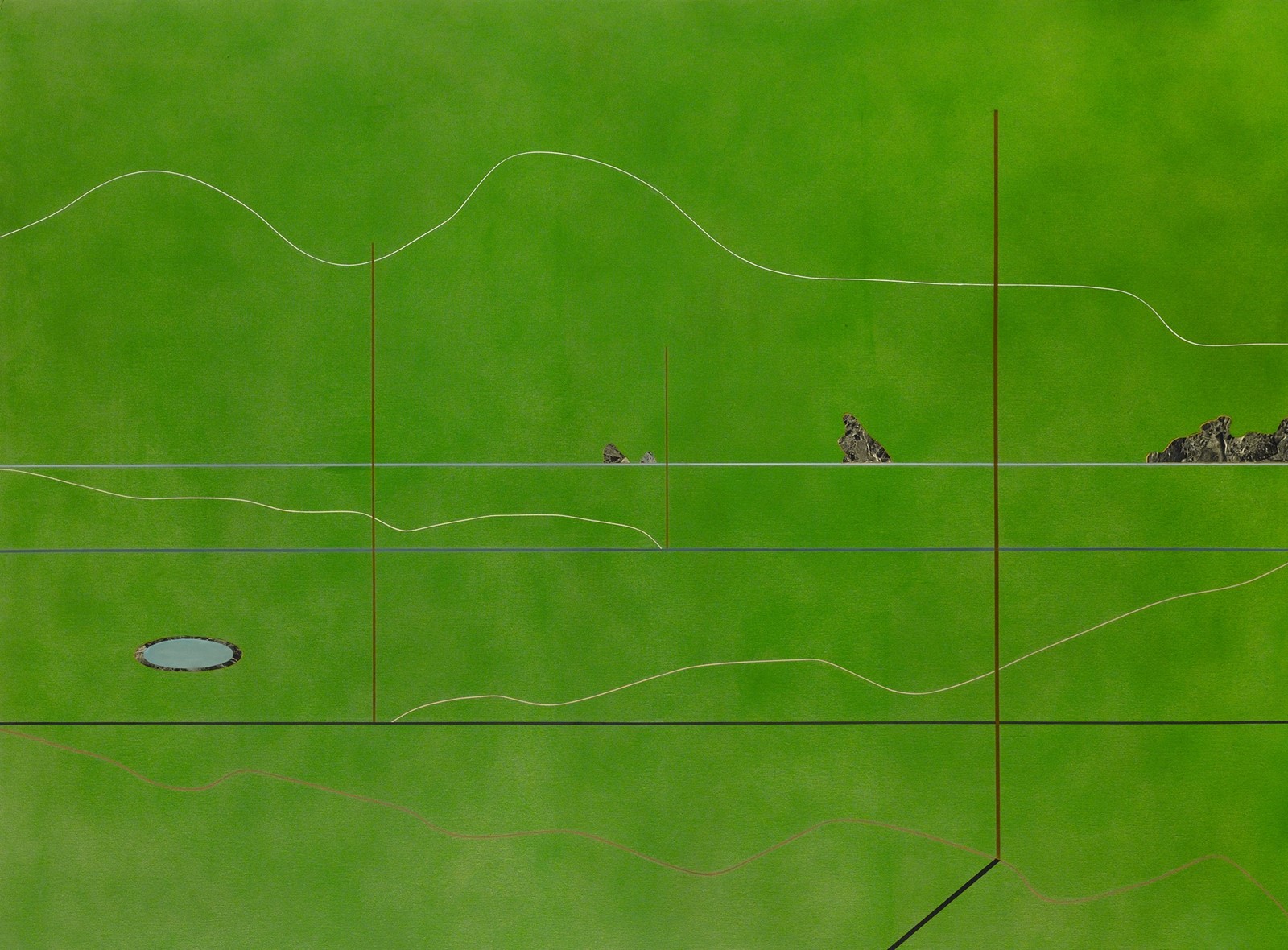

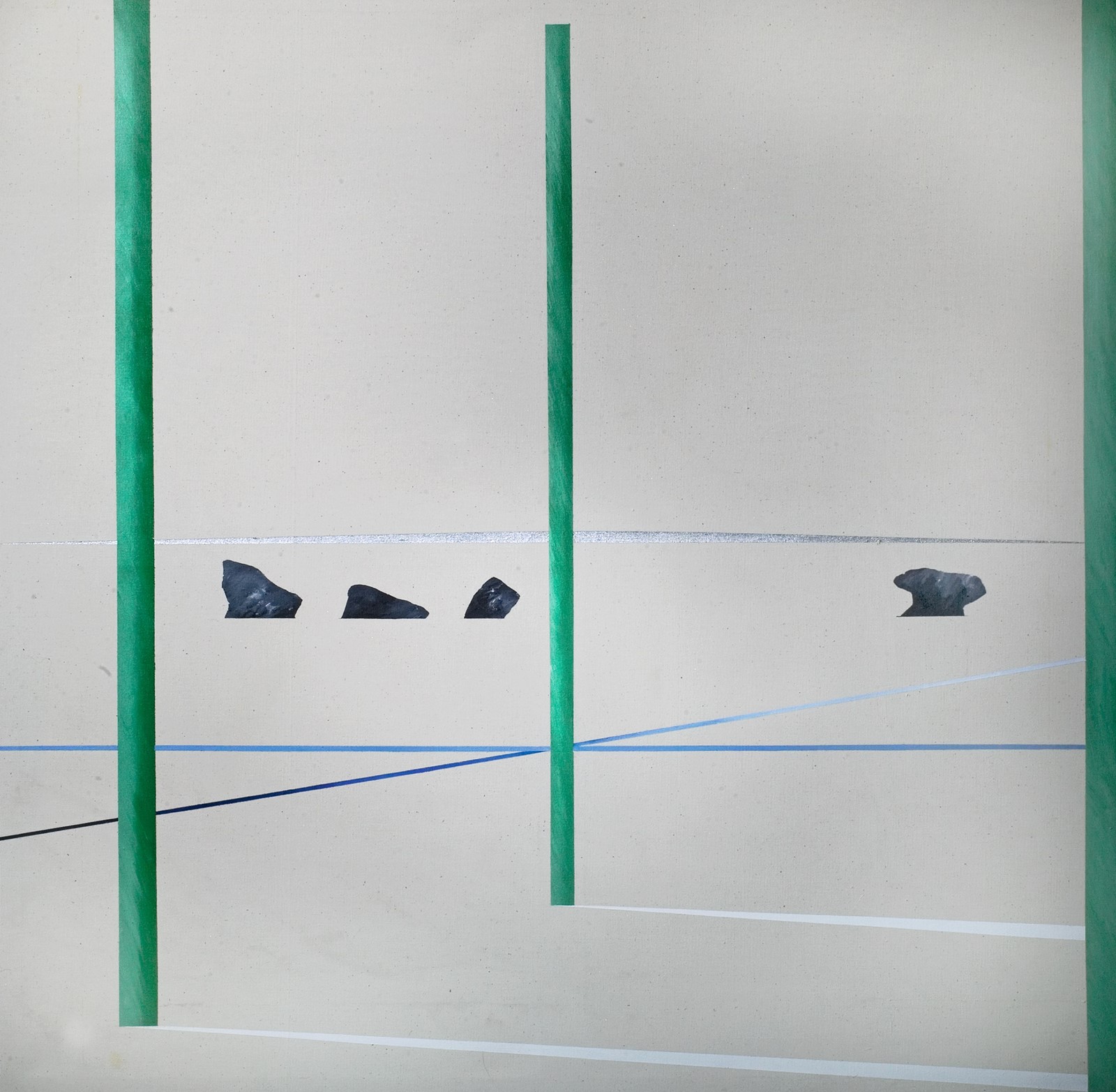

Many strands made up Derek Jarman’s work – humour, torrential creativity, romanticism and a palpable political anger that burned during the dog days of Thatcherism. His career stretched across more than three decades, spent in the trenches of independent film-making. Starting out in a Thames-side warehouse, where he would gather a shifting circle of radically dressed partners in crime, he eventually moved out to his neat wooden cottage in Dungeness, Kent, with its eccentric garden creeping out through the shingle. He was a magpie-like collector of people, and over the following pages we have gathered a few of those who count themselves fortunate to have known and worked with him, as well as a younger generation who continue to be inspired by his legacy. Each recommends an excerpt from his writings, which are illustrated by a selection of his paintings, to coincide with the Irish Museum of Modern Art’s PROTEST! exhibition, a major retrospective that opens in November. The show will weave together all the diverse elements of Jarman’s work for the first time – his films, paintings, theatre design, music videos, writings and gardening. Revisiting his work in newly turbulent times, it’s hard not to feel how deeply his voice of creativity and dissent is missing from the fray.

Tilda Swinton

“It’s strange to propose this, because Derek mentions me in it. But maybe it’s precise enough to hold water…”

The I of the Storm, Kicking the Pricks

When Tilda dances at the end of The Last of England she moves into the eye of a storm. I can feel the audience flattened against their seats; if someone dropped a sweet wrapper it would take off and swirl round the room; something vast is conjured, which buffers you so remorselessly, even memories of the preceding hour are blown from your mind. As you are hurled into the vortex you expect Mr Turner to loom out of the mists lashed to the mast, paintbrush in hand.

Ford Madox Brown: “Mr Turner, I presume?”

Those neat émigrés setting off for a new life in the new world would be buffeted by storms like this before they rebuilt their homes in Canterbury. Perhaps as they sailed down the estuary they heard the heron’s mournful call. Perhaps they felt they were crossing the Styx, like these shades, sailing past the sunset into the night.

Chook Chack Chack

Three rising notes in the silence, and the film goes dark. The names of my friends float by, the projector is off, what a relief, what did you see? What did I see?

Was it about anything?

nothing

something

I’m not sure, why don’t you tell me?

But if you ask me was it worth it?

I’d say yes

Goodnight, Thankyou

For your borrowed time

Tilda Swinton once described Derek Jarman as having a “perennial beginner’s mind”. It’s a description that might easily be applied to her, too. The actor’s fresh-eyed curiosity, anarchic spirit and instinct for collecting conspirators were all forged in the intensely creative collaboration she shared with Jarman. Swinton made her debut in Caravaggio (1986), and the pair continued to work and play together until his death in 1994.

[Excerpt from Kicking the Pricks by Derek Jarman, originally published in 1987 as The Last of England by Constable and Company Ltd.]

Olivia Laing

“I’ve been reading Derek Jarman since I was a child. His influence is there in every phase and facet of my life – as an activist, a writer, a gardener, as a human in the 21st century. Take down the fences, that’s Derek’s message. Keep making what you love. Keep making love. Steal cuttings. Crosspollinate. Plant a garden, even at the end of the world.”

How We Met: Derek Jarman and Kevin Collins

DEREK JARMAN: I was in Newcastle … it’ll be seven years ago this October … on the panel of the Tyneside Film Festival. Kevin kept appearing in the front row. He was very well – expensively – dressed; you couldn’t not notice him because everybody else had anoraks and sweaters and T-shirts. I went up to him to say hello, and said we all wanted to go to this club called Rock Shots. But he said: “I never go to nightclubs.” I asked him if he would show us where it was, as we didn’t know. Lies, of course, all lies.

He left us at the door and the next day, I came back to London. I really wanted to meet him again. In about December, I thought: “This is crazy,” so I rang Peter Packer who ran the festival, and said: “Do you know that young man who was in the front row?” “Oh,” he replied. “Him. He’s trouble.” He gave me his number and I rang him on New Year’s Eve to say Happy New Year. There was this deathly hush, but I said: “If you ever come to London, you’re welcome to stay … ” and two weeks later he did.

When he first visited – with his little bag over his shoulder – he’d never been to London before and he was very Geordie about it: “Why should I want to come to London?”, you know. But he was working on computers at the time – very high powered – and I think he was fed up with it. So by March, I suggested he came and lived in my flat in the Charing Cross Road while I was at my home in Dungeness. That’s the story. He came down and has lived in this room ever since. It’s rather romantic really, as stories go. I think it shows considerable daring to actually ring someone up. Odd that it should work out as the best relationship of my life.

We’ve never argued, which seems amazing to me. Other people hammer each other, lay little mines. Kevin thinks I sabotage his hair – he feels I have a vested interest in making him look as unkempt as possible to make me look better. But, apart from that and Coronation Street, which he loves and I’ll do anything to avoid, that’s about it. Perhaps it works so well because we’re so different. There’s the huge age gap to start off: I’m an old colonel and he’s a young subaltern. And we’re quite good at giving each other space – for instance, he goes back to Newcastle every two weeks for the weekend and I go down to my house in Dungeness. It’s platonic – sort of, anyway – but whatever it is, it works.

We don’t do an awful lot together. He likes going to the cinema, and I’ve become less and less inclined to go out. He’ll cook his meals – it’ll be things like marrowfat peas and corn, proper Geordie fare. But I’m a middle-class foodie, so I’ll have pasta with pesto or something. Sometimes, all I’ve got is a tangerine … I’m a terrible snob, especially about visual things, but I’m very good at covering it up. I rather like Kevin’s clothes – I can just squeeze into them. But he’s very possessive about them; every now and again I find something on my pile – a pullover or something – and it looks as though it might be mine …

I suppose what I like most about Kevin is his seriousness – he was brought up a Methodist and has very old-fashioned values. He had a very stable upbringing and has a sense of place, which I never had. I was a forces child and my father was a New Zealander. It’s nice to come home to someone who has a sense of place.

The other thing about Kevin is he never goes ‘out’. I’m not certain about Newcastle – I’ve never asked. He says he sits in and watches TV. I used to go ‘out’ – Hampstead Heath for one thing – but I don’t any longer. We really are the most anti-social people you could possibly meet.

I have to say illness has bound the relationship together in an odd sort of way – you know, one’s imminent dissolution at any moment. I don’t know if that has altered the relationship, but it’s certainly part of it. It would be silly not to acknowledge that. I’m a fulltime occupation in one way or another, and there was a moment when he was offered a video editing job and turned it down because I was ill … He’s the most caring person you could imagine – he won’t let me into the kitchen. His favourite new toy is this new washing machine. I think if he were asked what he liked best in the world, it would be a conflict between me and this Bosch thing.

KEVIN COLLINS: I was sitting three rows from the back at the film festival, not flaunting myself in the front row. I was wearing a suit because I’d come from work, and I wouldn’t go to the club out of principle, because I’d been queer-bashed with a friend once and they wouldn’t let us in to ring for an ambulance. The festival also gave a reception which I was invited to and, while I was there, Derek handed me a piece of paper which said: “Don’t disappear. Derek”, with his phone number on it. What a strange thing, I thought. Anyway, about a fortnight later, I got a letter from him inviting me to stay. I showed it to Peter Packer and he said, “Oh, don’t go. Derek is heavily into S&M.” So I wrote back saying: “Sorry Derek, I’m busy for the next five years.”

But he wrote to me again, saying that he was editing The Last of England, which he thought I might find interesting. As I was going down to London for a job interview, I went to visit him. It was seven o’clock in the morning when I knocked on the door. Before I went in, I said: “Are you into S&M?” and he said, “Oh I’m sorry, no” – as if I’d be disappointed – so that was a relief. But, as I went to give him a kiss, he turned his head away and said, “You can’t kiss me, I’ve got HIV,” and I said: “Well, that’s all right. I haven’t come to London for that, in any case.”

At that point, Derek was twice my age – though the gap seems to be shrinking now. We don’t sleep together: Derek’s always been too old for me, and I’ve always been too old for Derek – he likes younger men. I go back to Newcastle to visit my boyfriend every other week, while Derek has his bits of fluff on the side. He likes to have his image of propriety, but he’s always popping up to Hampstead. When he’s got that glint in his eye, I sometimes say: “Leave me a note to say where you’re going, so I can clutch it to my breast at your funeral after you’ve been queer-bashed.” It’s one of our little jokes. He’s just a big kid, really.

He’s a terrible snob, is Derek. I like Co-op brand tea, which he calls working-class tea. “I like working-class tea,” he’ll say, but he won’t finish it. Another time, I cooked him some fish fingers and he said: “Oh, how interesting. Fish fillets in breadcrumbs. Are they new?” He also has this really irritating habit of calling me “Hinny Beast”. Hinny’s a Geordie endearment. We’ll go to restaurants and he’ll say: “You can’t eat that, it’s not hinny beast food.”

Once, I was introduced to someone as the Hinny Beast. I’ve tried to wean him off it, but he won’t stop. It’s very embarrassing.

The caring business has always been part of the deal. When I first got here, Derek wasn’t very good at looking after himself; the kitchen was in a bit of a state. I don’t want to be a little housewife or anything. Bloody hell, no way. But I do feel very responsible for him. I don’t want to leave Derek. But if I did, there would be that stopping me. He says he doesn’t mind me going to Newcastle, but there was this period for a while when, whenever I went, he broke something – a cup, a door handle. I’d like to think he did it out of jealousy, but maybe he was just clumsier without me.

In a way, I’m prepared for his death. Last time, after Derek had been in hospital under observation, I went to pick him up. They give you these grey polythene bags to put your stuff in. I’d packed them up and said, “Come on, Derek.” But he replied: “I’m not coming.” He just didn’t feel well enough to come home. So I left him there and took all his property with me. I felt really cheated. I’d put the heating up high, and bought M&S crème brûlée in specially. I’d gone to the hospital to get him and left without him. I sat at home on my own, and it felt as if he’d died.

Most of all I like Derek because he’s round the twist. I’m very fortunate to have full-time access to a genius. We’ve been working on a script together and he knows exactly what it needs and where. It’s incredible, it’s like a spark.

Our relationship is very unusual – we’re not lovers or boyfriends. I tell you what we’re like: James Fox and Dirk Bogarde in The Servant. I’m always saying things like: “If I may be so bold, sir, my quiche comes highly recommended.”

Olivia Laing’s work encompasses non-fiction books including The Trip to Echo Spring, a lyrical meditation on writing and alcoholism in which she train hops across America, encountering the ghosts of troubled authors; The Lonely City, a haunting elegy on loneliness and art; and her first novel, Crudo, which channels the spirit of post-punk pioneer Kathy Acker. She also cultivates a Jarman-like garden that is as wild and beautiful as her writing.

[Interview by Sabine Durrant, first printed in the Independent on Sunday, 17 January 1993.]

Sandy Powell

“I have recently been leafing through Smiling in Slow Motion, partly because it heavily features my dear friend Keith [AKA Kevin] Collins, or HB, who sadly passed away last year.

“All of Derek’s writing is so beautifully articulate, descriptive and full of humour, even at the worst of times. His references to Keith are filled with such love, tenderness and appreciation of everything he did it’s hard to pick a favourite. However I have chosen the snippet below as it also reminds me of Keith’s wicked sense of humour and how much I miss them both.”

(Tuesday 9 July 1991)

Caught a cab at 9.30 to the Heath. Very hot, met Julian. HB had sabotaged my armoury – KY replaced with a tube of Deep Heat and my bottle of poppers filled with perfume.

Costume designer Sandy Powell’s first film was Caravaggio in 1986. She has since won three Academy Awards and worked with the likes of Martin Scorsese, Todd Haynes and, most recently, Yorgos Lanthimos for The Favourite, conjuring a punk-rock royal court out of foraged denim and vinyl that would have delighted Jarman’s mischievous spirit.

[Excerpt from Smiling in Slow Motion: Diaries, 1991-1994, first published in 2000 by Century.]

John Waters

“I saw Blue in its opening week in New York, in 1993. There was a big sign outside the movie theatre that read, ‘Warning, this film is only the colour blue’. Talk about a marketing nightmare! People had flipped out and wanted their money back. Blue is as beautiful as a minimalist art piece. It’s hypnotising. You feel like you’re tripping after a while. Derek Jarman was going blind as he made it, and Blue was a beautiful, radical way to deal with dying from Aids. Half of my friends died of Aids in the ’80s, so it’s a tear-jerker – but it’s not self-pitying. It’s smart, angry and very, very sad. Minimalist cinema is a small genre, but this would be the Rosebud of minimalist cinema. It’s extreme, and it completely defied the movie business. I felt Derek was a kindred spirit. We made very different movies, but I saw all of his. Tilda Swinton was his Divine, right?”

You say to the boy open your eyes

When he opens his eyes and sees the light

You make him cry out. Saying

O Blue come forth

O Blue arise

O Blue ascend

O Blue come in.

I am sitting with some friends in this cafe drinking coffee served by young refugees from Bosnia. The war rages across the newspapers and through the ruined streets of Sarajevo.

Tania said, “Your clothes are on back to front and inside out.” Since there were only two of us here I took them off and put them right then and there. I am always here before the doors open.

What need of so much news from abroad while all that concerns either life or death is all transacting and at work within me?

I step off the kerb and a cyclist nearly knocks me down. Flying in from the dark he nearly parted my hair.

I step into a blue funk.

The doctor in St Bartholomew’s Hospital thought he could detect lesions in my retina – the pupils dilated with belladonna – the torch shone into them with a terrible blinding light.

Look left

Look down

Look up

Look right.

Blue flashes in my eyes.

Blue Bottle Buzzing

Lazy days

The sky blue butterfly

Sways on a cornflower

Lost in the warmth

Of the blue heat haze

Singing the blues

Quiet and slowly

Blue of my heart

Blue of my dreams

Slow blue love

Of delphinium days.

Blue is the universal love in which man bathes – it is the terrestrial paradise.

Baltimore-based film-maker John Waters has made exuberantly warped cinema for more than five decades, from his first Super 8 short Hag in a Black Leather Jacket to the notoriously filthy cult classic Pink Flamingos, and pitch-black comedy Cecil B Demented. He is also an author, stand-up comedian and will forever be The Pope of Trash, as anointed by William Burroughs.

[Excerpt from the transcript of Blue, written and directed by Derek Jarman, and produced by James Mackay and Takashi Asai. First broadcast, simultaneously, on Channel 4 and BBC Radio 3 on 19 September 1993.]

Luca Guadagnino

“Here’s the excerpt I’d like to propose, from Derek Jarman’s Blue.”

Our name will be forgotten

In time

No one will remember our work

Our life will pass like the traces of a cloud

And be scattered like

Mist that is chased by the

Rays of the sun

For our time is the passing of a shadow

And our lives will run like

Sparks through the stubble.

I place a delphinium, Blue, upon your grave.

Palermo-born auteur Luca Guadagnino has a kindred spirit and regular collaborator in Jarman’s muse Tilda Swinton. She has starred in his sweeping melodrama I Am Love, tracing the operatic downfall of a wealthy Milanese family; his sinister, sun-soaked mystery A Bigger Splash; and most recently, his remake of cult Seventies horror Suspiria.

[Excerpt from Blue, written and directed by Derek Jarman, 1993, © Basilisk Communications Limited.]

PROTEST! is at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, from November 15, 2019 – February 23, 2020.

A version of this story originally appeared in AnOther Magazine Autumn/Winter 2019, which is on sale internationally now.