Fondazione Prada’s new Venice exhibition marks 54 years of friendship between curator Germano Celant and the late artist Jannis Kounellis, a key figure of the Arte Povera movement

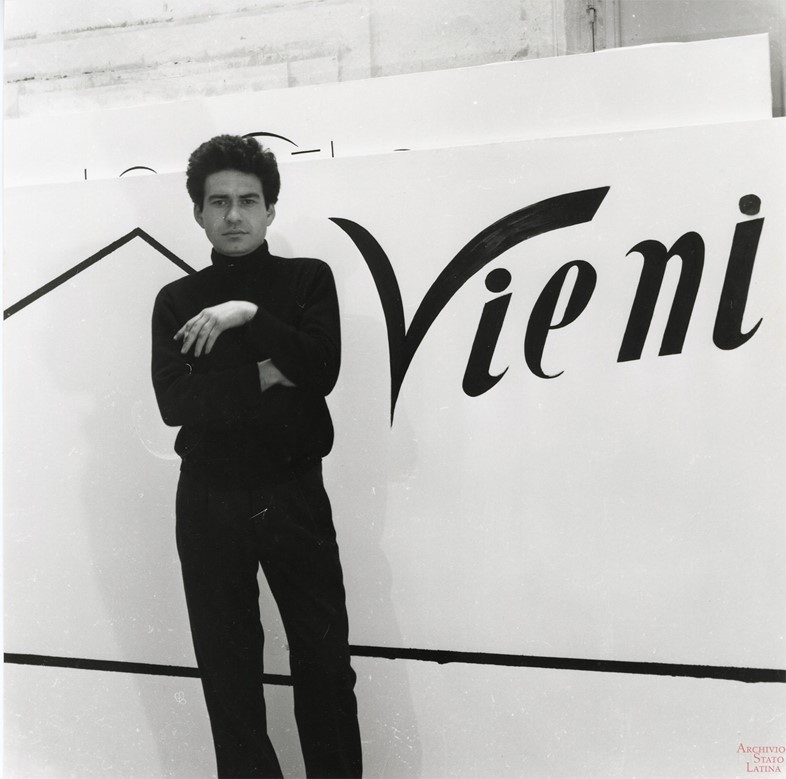

Germano Celant, Fondazione Prada’s excellently titled Artistic and Scientific Superintendent, goes way back with the subject of his latest show. “Oh my god, it was ‘62, ‘63,” he says of when he first met artist Jannis Kounellis. “I was 23 I think!” It was a good time for the pair to meet: Kounellis had recently moved to Rome, having abandoned his homeland, Greece, and – in theory – his heritage. Celant meanwhile, was “going around for a magazine to collect news for an arts calendar of all the exhibitions in Rome, Naples, wherever. “There was no money – I used to stay with the artists. It was easy to find them: you’d just go into Rosati Bar – the bar was the centre of the community at the time – where all the artists were and then they’d all know you were in town. Then you’d go to the restaurant, to their studio and that’s it. Then you become friends...”

Celant was then involved with the “Milano scene”, the optical art, design and ocular architecture that was influencing the artistic community in the city at the time. But the movement Kounellis belonged to was somewhat different: Celant named it Arte Povera, ‘poor art’. The term stuck, and has since defined the radical group who preferred to seek meaning from the physical: the everyday, the industrial, the natural, found objects, and the body. Examples of each, just as arresting today, comprise the Fondazione Prada’s new Venice show, Jannis Kounellis, which occupies the grand frescoed halls of the foundation’s palazzo, Ca’ Corner della Regina now, until November 24.

Born in 1936, Kounellis only died in 2017, and this exhibition curated by his dear friend is the first to survey his works chronologically. “It’s 54 years of friendship,” Celant explains. “I’ve always been part of his research, catalogues, publications, essays. We shared so much time together, in Japan, all over the world – I was part of his spirit. When he died, I asked his companion Michelle (Coudray), ‘Can we do a show?’ But the show without him is totally different. He was so contemporary, he would never have done it chronologically. He was always mixing. It was never the idea to be linear because creativity has no time for him. We cannot repeat him, that’s impossible.”

And so, the show subverts Kounellis’ approach entirely – but his disruptive sentiment prevails as his play with hard and heavy scale interacts with its baroque surroundings. The exhibition proper starts with his typographical works: vast white canvases stenciled sparsely with letters and numerals, which he called “phonetic poems”. On occasion he performed beside these stark graphic pieces, cloaked in a suit of white canvas, also covered in letters and numbers; wearing this he was camouflaged amid the paintings. In becoming the painting, he blew apart the notion of the painting as an object – and from here on in, he referred to all of his works as paintings, be that performance, music, objects, fire, animals, foodstuffs, dance. Each untitled, as if to blur the boundaries between them further still.

The works are timeless. Ascending the various pianos of the 18th-century building, viewers encounter all manner of heft and weight: a minimalism, rawness and tactility that is still immediate and direct today. A rustic wooden doorway filled with stones. Stark black vinyl-shine flowers painted onto unbleached linen and canvas. A room filled with gas canisters that would, on occasion, all go off at once and fill the room with flame bursts. A wrought iron bed, laden with rocks. A giant steel daisy – more resembling a circular saw than a delicate flower – attached to another gas canister, ready for propulsion. A grid of 2,400 tiny shot glasses of grappa – the astringent smell enlivening a white walled room. A stairway clad with steel scales, each topped with a precarious pyramid of pungent arabica coffee. A room, painted with 3,600 squares of gold leaf, foregrounded by a coat hanger with a man’s jacket – feathers of gold waft from the wall around the room in the light breeze. A vast flower bed made of rolled burlap sacks hosts a small collection of plants, the scent of the ample earth between them also filling the air. Elsewhere, a cellist plays a short loop of music, the notes of which are painted onto the canvas behind him; in the 70s when this piece was conceived, the musician would have played the music until he collapsed.

Each work, lavished with space amid the lofty halls of the building, marries modesty with grandeur, work with play, industry with nature – wool, iron, steel, earth, machinery and the body entwine in a tale of the inability to escape one’s history and society. As you traverse the building the feeling of scale soars and sinks, taking the audience with it effortlessly. One can see why Celant was so enamoured by his friend, way back when.

Jannis Kounellis is at Fondazione Prada until November 24, 2019.