I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating sees the Minnesota-based photographer shoot his subjects in their own spaces – here, he shares the story behind this publication

Photographer Alec Soth has garnered acclaim for his “grand narrative” projects, as he calls them, that have seen him travel across his native country of America. 2004’s Sleeping by the Mississippi saw Soth journey the length of the country’s longest river, documenting its people and landscapes over a period of five years; Niagara, published in 2006, was a study of love in the town known for its Falls; and for Songbook, 2015, he took on the guise of “suburban newspaper photographer” and photographed American social life state by state.

Soth’s new photography book, I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, is a quieter affair. This publication comes after the Minnesota-born image-maker took a year off from photographing, following a “full-on mystical experience”, as he explains in the book in a conversation with the author Hanya Yanagihara: “The only way to describe it is to say that I suddenly understood that everything is connected... This changed everything.” Where before there had been a distance in his practice, Soth returned to the medium seeking a new kind of engagement with his subjects; describing his previous approach as “more aggressive” and “like a hunter on the prowl”, there is a lightness behind his new work.

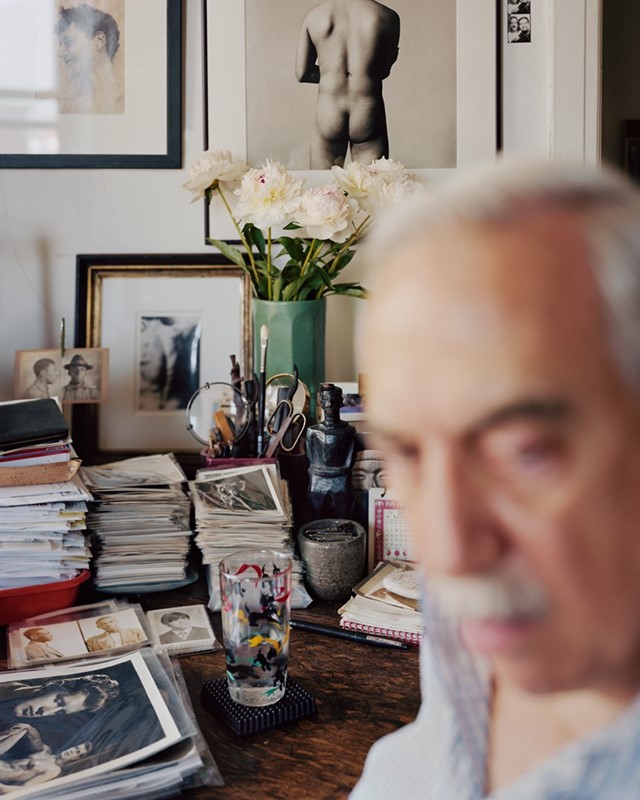

I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating is a series of 35 portraits and interiors images, made with a large format eight-by-ten inch camera, in which Soth captures people in their own spaces. Like previous projects, the series took him around the world, but creating these images became an incidental occurrence wherever he happened to be travelling. “I didn’t want it defined by geography,” Soth tells AnOther over the phone. “Locations just kind of came to me. I would get invited to give a lecture in Odessa or something, and then I would find someone there who was a helper who would send me photographs of people or social media accounts or what have you, and I would say to them ‘I’m kind of looking for someone who inhabits space in this interesting way’.”

Featuring 35 images in the book – though more photographs will be shown as part of forthcoming exhibitions – was important for Soth. “Early on I had this number – 35 – and that was my target number. I wanted there to be this openness and lightness that I was feeling, and to have plenty of space for the pictures, but also not a lot of pictures... I wanted air.” This space offered by the book’s large pages and sparse layout counteracts the closeness of the portraits, which are intimate by nature of depicting people and their own spaces. Soth deliberately offers little information about his subjects, and by often photographing them through a barrier – dancer Anna Halprin is captured through a window, for example, while Yanagihara is seen through the gaps in a bookshelf – there is a distinct awareness that all we are seeing is a glimpse of the person. “Photography has to have space and distance, so I’m in an interior space but I can only know so much about them, and that is kind of reflected in the book’s title [taken from a Wallace Stevens poem, The Gray Room].”

“There is this experience with the camera I used in this project. You’re tucked under the dark cloth, you’re hidden, and you’re looking at this picture – albeit upside down – but you’re looking at the subjects and you use this little magnifying glass and can look right in to their eyes. It’s just such an incredible, sensual feeling; it’s such a delight. And the photograph is a representation of that strange intimacy-slash-distance.”

People engage with human stories – whether they’re told through photography, a film, a poem or another form. “We’re human beings and we’re trying to figure out how these other human beings around us are functioning, natural,” as the photographer says. While Soth spent time ruminating on the nature of photography, what remained was a desire to tell people’s stories (even if it’s just a smallest fraction of them). A new outlook meant involving his subjects more: “I’m spending time getting to know them a little bit, and I do think that the photographs are a little bit more collaborative; the other people are rich complicated people with lives and hopes and dreams and everything else, and this is just a picture of them – but it’s made by me and it’s chosen by me and it has lots of ‘me’ elements in it, so it’s really a picture of the relationship between these two people in this space at that time. I was trying to be more responsive to what they were saying about themselves or their likes and dislikes and what have you. I was also just trying to be a little bit more sensitive than I’ve been in the past.”

People are key to Soth’s practice; he describes them to Yanagihara as “like the gasoline” for a picture. Though some images in the book don’t feature a person, there is a feeling of human presence in the unique interior spaces. Some recurring motifs “kept emerging” throughout the process of creating the photographs: “flowers, birds, and then there were these books, there are a number of pictures with books in them,” says Soth. “Photographing a book is kind of like photographing a person, because you can’t read the book, you’re just inferring what is in the book. A book of portraits is sort of like looking at a library shelf in a way.”

Soth goes on to compare a series of photographs to poetry (where a film might be a novel), due to the gaps it can leave for the viewer to fill in – something which I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating does expertly. “There are books where you write the whole story and it’s right next to the picture and that can really kill it, so you just have to be careful to not destroy pictures for people. And like poetry, the photobook, the form of it, has rhythm and the page turning is sort of like a line break. The poet Mary Oliver, who recently passed away, talked about how as she got older, her poems just kept getting shorter and shorter. I’m wondering if that’s going to happen to me, and that maybe my next book is going to have 20 pictures in it.”

I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating by Alec Soth is published by MACK.