Tom Rasmussen speaks to the Canadian drag artist about their series of films that play with the concept of performance and ideas of pre-established looking

Victoria Sin is the best drag queen I’ve ever seen. Of course, as a drag queen myself, I have a tendency to speak in hyperbole. But this is not that, because Victoria Sin is the best drag queen I’ve ever seen.

Why? Well, first – they are a spellbinding performer. Coming up through the London scene as that queen who butters bread and makes you watch while they drink a glass of milk, Sin’s consumption of space as a non-binary drag queen assigned female at birth commands that you think about marginalised bodies, the labour of femininity, and who gets to be valid in queer spaces all in one sip on a straw. That, when we all first experienced it, there in the basement at Vogue Fabrics, was a mind-blowing concept that Victoria made clear without even a word.

And they continue to blow minds, but now they’ve moved their practice into the art world. We speak over WhatsApp, from my bed in London to the kitchen of Taipei’s Chi-Wen gallery, where Victoria is preparing for a performance. Across our conversation they tell me about the fallibility of language, their love and focus on speculative fiction, and their show at Sotheby’s S2 – which is ongoing as we speak, which you must see, which is utterly remarkable – Narrative Reflections on Looking.

Tom Rasmussen: What are you up to right now?

Victoria Sin: At this very moment? At this very moment I am in the kitchen of Chi-Wen gallery in Taipei looking down at my notebook which I have almost completely filled writing out the words to a performance that I will perform on Wednesday.

TR: Can you tell me a bit about that performance?

VS: Sure, I would love to. The performance is about language. It’s about how language not only gives shape to thought but also shapes thought. So words that we’re given have a predetermined meaning. And so, for example, take gender: when a kid is born and you give them a name – either literally a name, which is often gendered, or the name of either male or female, the name actually comes before that child’s experience, and it shapes their experience for the rest of their lives. So it’s like how do we use language in this way? For me, with the English language, how do we express thoughts or ideas that are truly queer or truly feminist or truly post-colonial when the English language is so steeped in its creation and its use, so steeped in transphobia, patriarchy, histories of colonialism. A really good example is how cisgender people are not often called cisgender people – cisgender people are often considered the norm. And so you name something in order to differentiate. There’s a recurring line in the performance which is: “Naming is an act of mastery, and I would hope to never do that to you.” How do we use a language which is so patriarchal, which is so colonial, to express thoughts that are really, truly, queer and feminist. Think about the Audre Lorde quote: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

TR: Is it about repurposing the tools or making new tools?

VS: It’s about trying to come up with a different way of expressing yourself. So, I’m also performing with a local Taiwanese pipa player – and a pipa is often called a Chinese loot – the performer studied the style which is called Pudong, which is the most difficult and the most expressive, and this is a very poetic and very different style of playing it. So, within this kind of instrument it can express things that you could never with words. Emotions that we don’t even have names for, right? But I’m trying to bring in these things which are often missing from language which can be incredibly cold. Language often really over-simplifies how complex it can be to live in the world as an individual, in this vastly and increasingly challenging social context. So within the performance I try to speak about my identity without naming it.

TR: Are you going to bring it to London?

VS: I’m not sure. It feels really right here. I could see it travelling, but the instrument would change depending on the context it was in. Because I think that this instrument is one which, outside of a Taiwanese or Chinese context would be very exoticised. It’s incredibly important to think about the context in which the work is performed, and something which is taken one way in a certain context will be taken completely differently in another context and as an artist you have to be very aware of that.

TR: Speaking of context. Using narrative film as a medium: let’s talk about the S2 show, and how you use film to prevent your drag from being ill-consumed and exoticised.

VS: So it’s a series of films called Narrative Reflections on Looking. It took me a really long time to bring drag into my work. For a long time I kept the two very separate. I had my life that I led in my practice in art school, and then I had my life that I lead outside of school and in the club at night. And I was very protective about my drag, because drag was something that I really did for me, it was something I really loved doing. And when you introduce drag – especially drag queens – into a world that is incredibly heteronormative, and patriarchal and white, like so many art institutions, and the art world can be, they are very easily exoticised and taken out of context. They can become a kind of freak-show. And I wanted to make sure that the way that I brought it in was a way where it wouldn’t just be exoticised in that way, and for me narrative film was that.

Narrative cinema. You are controlling the gaze of the camera on the subject, which was me in drag. And of course you’re telling the story. Of course it’s not complete control, you can never control how people consume the work completely. And I also wanted to talk about systems of looking. Which are very much constructed, especially in Hollywood cinema, and have created systems of looking and iconographies of femininity and so to be able to use the language of film was really important for me.

TR: Are you actively playing with ideas of pre-established looking?

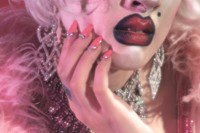

VS: Definitely. That’s the whole thing with using the language of cinema, you know? Like within Narrative Reflections on Looking there’s always the creeping gaze of the camera which starts from the feet and moves up. And when you start with the feet you think you’re gonna get something, but by the time you end up on the face you realise you’re looking at something else entirely. Basically, what I’m trying to do with that is that same thing I’m doing with my drag. You start off by letting people be comfortable: you start off with what seems like systems of looking that they’re very used to, lulling them into a false sense of security – “oh I’m just going to be consuming this image of a beautiful woman” – but it turns out that they’re actually looking at something a little more sinister and a lot more queer.

TR: So that also ties into the question of what you’re looking at with your drag. Can you explain the sinister side?

VS: In Narrative Reflections on Looking I can say that my influences come from old Hollywood, iconographies of western femininities, so you know there’s definitely Marilyn Monroe, Marlene Dietrich, Jessica Rabbit, and these cartoon-ish caricatures of Western femininity. But the sinister element is that when you look at a drag queen from far away you’re often not very sure whether it’s a drag queen, things become apparent the closer you get. The way that I think about my drag is that I’m not just trying to criticise beauty ideals, we live with them, they’re very deeply ingrained, in our psyche and our systems of desire. I’m trying to acknowledge that, yes, I did grow up in a society that told me that I wanted to be all of these things, and actually I do enjoy being all of these things and doing all of this drag. I love being this super sexed up vixen, Hollywood, giant blonde hair, super glamorous creature. But you can enjoy these things, and know that they’re constructed. Enjoy them and know that they’re fake.

TR: Would you say it’s visual speculative fiction that you’re engaging in then?

VS: Yeah, sure, I think about drag as an embodied speculative fiction, as a space for fantasy, where you can use this medium which is very playful to talk about things that can be really serious in an interesting and enticing way. Which is what good science fiction does too – it uses fantasy and play to speak about things which are serious.

TR: So what’s in the films?

VS: Well, one of them comes from the experience of looking at images of really skinny white girls in teen magazine and the kind of desire I had looking at these images. A lot of my work is about our relationships with images, and how those relationships change us.

TR: In what way?

VS: I think within mainstream media, images are incredibly gendered and that’s how advertising works – we’re presented with an image which is incredibly far from the image you have of yourself, making you feel like you have and incredible lack. The more anxiety you produce in a consumer, the more likely a consumer is to buy into achieving that image.

TR: But then in the visual you are becoming that image?

VS: Right, yes, that’s what the film series is about in drag – clowning these ideals I’ve always been told that I want to be. That are so embedded in systems of looking and desire. So I’m undermining it by saying that yes I can do that – I can be a glamorous, tall, big breasted, white woman. Why not? What’s stopping me? Nothing. So here you go.

I want people to look at the films and be able to relate to the experiences in them, and I want people to look at the images and find themselves looking at themselves more than they’re looking at me. Go and see the show. Then the ball will drop.

Narrative Reflections on Looking is at Sotheby’s S2 until January 25, 2019.