A new exhibition spotlights Jeanne Mandello, Hildegard Rosenthal and Grete Stern, who left Europe for South America in times of political unrest

The exhibition De l’autre côté (The Other Side) spotlights three little-known 20th-century female photographers with similar trajectories. Each born in Germany, they respectively fled to South America at the end of the 1930s to escape Europe’s menacing sociopolitical reality. Although shown together at the Maison de l’Amérique Latine in Paris, Jeanne Mandello, Hildegard Rosenthal and Grete Stern had no aesthetic overlap, only circumstantial similarities and a shared spirit of feminist independence and creative vision.

Their photographic practices were not only about self-expression but also a means by which to mingle with other progressive visionaries (architects, painters, thinkers) and communicate even as they were thrown into foreign contexts. Photography was – and remains – access to a sense of connectivity beyond language, of cultural participation if only through observation.

The show features 150 photos between the three women who began their careers in Berlin, Paris and London respectively before seeking refuge across the Atlantic. Their stories are uncannily resonant today as the world is plagued by governmental precarity, forced exile, the rise of anti-Semitism and – less menancingly – a fervent interest in discovering overlooked oeuvres by women and seeing how they experienced and depicted history.

1. Jeanne Mandello

Mandello – née Johanna – was born in Frankfurt in 1907. She grew up in a bourgeois Jewish family and was introduced to photography through her grandfather. She went to a professional school for two years and studied under Paul Wolff, who wrote extensively about the Leica camera, and restyled herself as Jeanne when she emigrated in 1934 to Paris. She had an atelier in the 17th arrondissement and did commissions for fashion houses – Balenciaga and Molyneux among them – contributed to French Vogue, and experimented with solarisations, photogrammes and photomontages.

As Jewish refugees, her status in France became dicey; she was arrested and sent to a camp in Gurs in 1940, although luckily liberated during an armistice. She and her husband bolted for Uruguay in 1941 – the country accepted 10,000 Jewish refugees during that period – and the couple left their entire photographic oeuvre up to that point behind. In Uruguay, Mandello did reportages for local newspapers, as well as portraits of exiled artists (ballerinas, choreographers, poets); she also also photographed still lifes of plants (leaves, pine cones, et cetera). She left Uruguay in 1953 and moved definitively to Spain, where she used her Rolleiflex throughout the rest of her life.

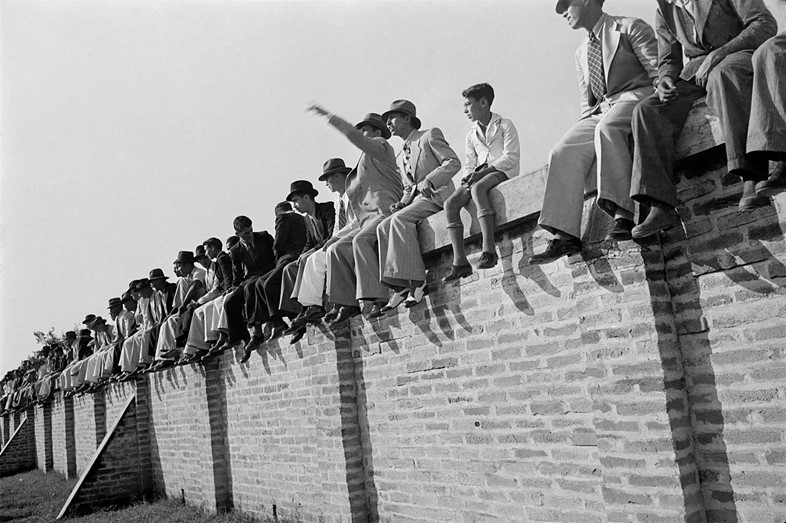

2. Hildegard Rosenthal

Rosenthal was born in 1913 in Frankfurt, where she actively practiced photography as an adolescent and won a local competition by age 16. Like Mandello, she was schooled in the studio of Paul Wolff, before absconding to São Paulo with her German Jewish fiancé. There she worked for a small local press agency and practiced street photography, cataloguing urban progress as industrialisation gained ground with increasing amounts of factories and businesses. She captured the dense frenzy of the city, as well as more pensive moments: a woman staring at her reflection as she got her hair cut; an elegant silhouette, back to the viewer, under an umbrella. She did portraits of poets and pianists, strangers reading the newspaper in cafés and in the street, capturing the eerie luminous effects of neon signs. When she had her daughter in 1948, she stopped her professional photography trajectory.

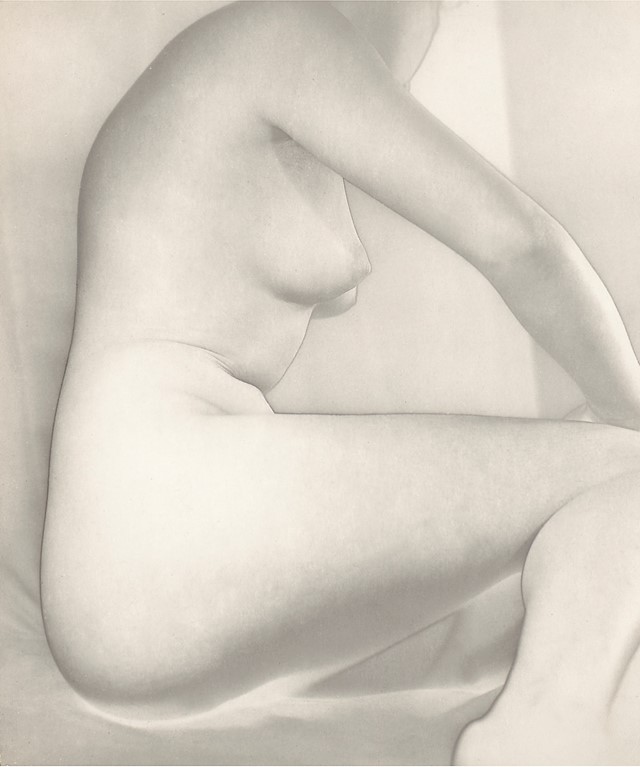

3. Grete Stern

Stern was born in Wuppertal in 1904, growing up in a comfortable family who worked in textiles. She moved to Berlin in 1927, and studied photography with members of the Bauhaus (the conceptual school that opened in Dessau and closed in 1933 under duress from the Nazi regime) before opening her own studio. She worked with another artist, Ellen Auerbach, and they signed their collaborative visuals – a mix of photomontage, collage, and typography fashioned in a studio setting – as ‘ringl+pit’. They applied their playful and Dada-inflected graphic style to ad campaigns for hair dye and perfumes; they also contributed to publishing platforms like the prestigious French arts magazine Cahiers d’Art. Stern moved to London, frequenting an artsy crowd, like Bertolt Brecht and his actress girlfriend Helene Weigel, but left for Buenos Aires with her Argentinian husband in 1936 as commissions ceased and the creative landscape became increasingly limited.

In South America, she lived in a Bauhaus-inspired house dubbed “the factory,” and photographed painters to dancers, many also in exile for being anti-Fascist. Her mid-century output became her most iconic: she contributed regularly to an Argentine magazine Idilio with the series Sueños (Dreams), creating an incredibly funny and Surrealist spectrum of collages based on Jungian psychology to accompany advice-seeking questions women addressed to the magazine. It’s a fever dream of vignettes that skewer domestic expectations and gender hierarchy; a sly feminist manifesto articulated through cheeky visuals. In one photomontage, a woman gapes at a suited man with a turtle head emerging from the collar (Love Without Illusion, 1950); elsewhere, a woman’s silhouettes props up a lampshade as a man reaches to light it (Household Electronics, 1949). Stern transformed and deconstructed the limited expectations of the female experience, with a wink, into something absurd.

De l’autre côté runs at Maison de l’Amérique Latine until December 20, 2018.