Impressive for both its scope and unfailing critical gaze, Jesse Darling’s work takes from a wide range of sources – from early Christian theology and Renaissance painting to Marxist feminist theory and scientific papers – to question the patriarchal structures that continue to surround us. In their upcoming show at Tate Britain, Darling turns a weary and wary eye to the twin institutions of museum and church and explores the story of St. Jerome and the lion, at the same time addressing the relationship between care and surveillance, the fragility of the body and art as a strategy for survival.

On their upcoming show at Tate Britain...

“The whole show is kind of a riff on museum and church aesthetics and the visuals of old imperial epistemology – the glass vitrine, the frame. When there’s something quite small in a great big box then hopefully you get the sense of a pinned butterfly, something that could otherwise have lived in the wild but never will now. So these tiny little works I’m making are kind of like relics, like little bits of shit that allegedly came from some saint – you build this great big box around it and then it’s a thing. And that is basically what the whole show is trying to do. I wanted to kind of occupy that space and resist a little bit, resist what it does.”

On St. Jerome and the lion…

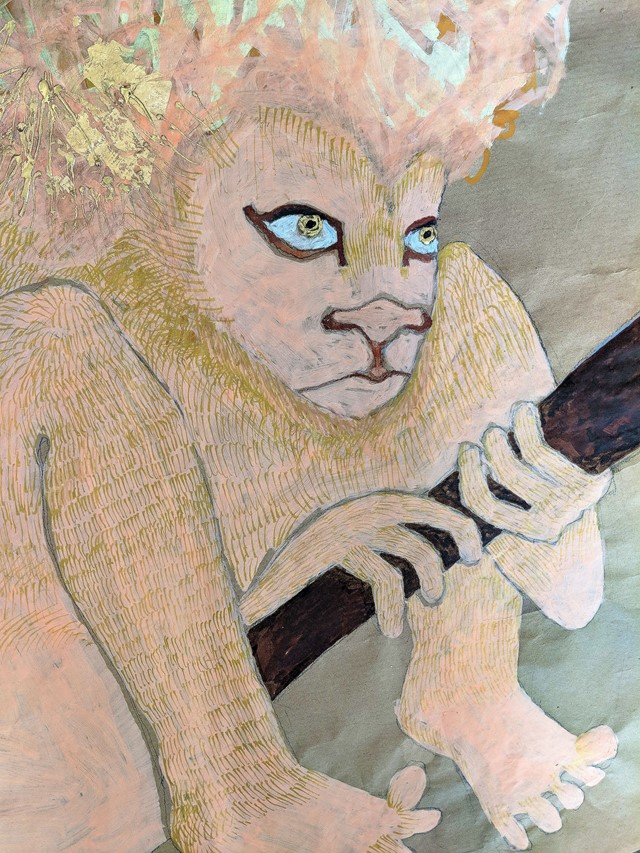

“St. Jerome and the lion appeared to me extraordinarily like a love story. The lion of course is this savage who showed up to where Jerome was studying. Everybody said they should kill the lion but Jerome said ‘No, he’s just wounded’ [and proceeded to remove a thorn from the lion’s paw], and I thought this was the most beautiful, romantic thing. That somebody would see you in your woundedness and say this is not dangerous or bad, this is just someone who’s hurting. I mean that’s what everyone wants, right? Then years went by and I kept thinking about it but also I got a bit of perspective on it, and started to do my own reading.

“So St. Jerome showed up in my work; he is nowhere but he is the museum. He’s the Tate, the institution, the church, the state, the medical-industrial complex, the white gaze, the male gaze. I am also Jerome in this context but I relate to the lion politically – though I have to acknowledge that I’m on both sides of that. By the time you’re having an institutional show, even though it is my first at the age of 38, I think you can’t pretend that you’re completely not of it.”

On understanding the ‘structural violence’ of the patriarchy...

“I don’t want to make it all about my own class and gender and sexual history or anything like that but the way that people come to understand themselves as mad or bad is also part of a structural violence. With the series of works called No more St. Jeromes, I was thinking, what if you didn’t have this paternalistic influence, the imperial understanding of bodies, when you enter the medical diagnostic industrial complex as a sick or crazy person? Like the church it styles itself as this benevolent relationship to the one seeking care, but that’s just one part of the story.”

On making art…

“I don’t call myself a research artist and I don’t make claims about what my work is doing – it doesn’t function like academia or activism, it’s just doing what art does. And that basically means that – whatever you take from it – you understand it in a register of the subjective. I don’t like things to be really slick or manufactured, the aesthetics of capital. I want you to see the decisions and the mistakes. That to me is an aesthetics of the subjective.”

Art Now: Jesse Darling: The Ballad of Saint Jerome runs until February 24, 2018 at Tate Britain, London.