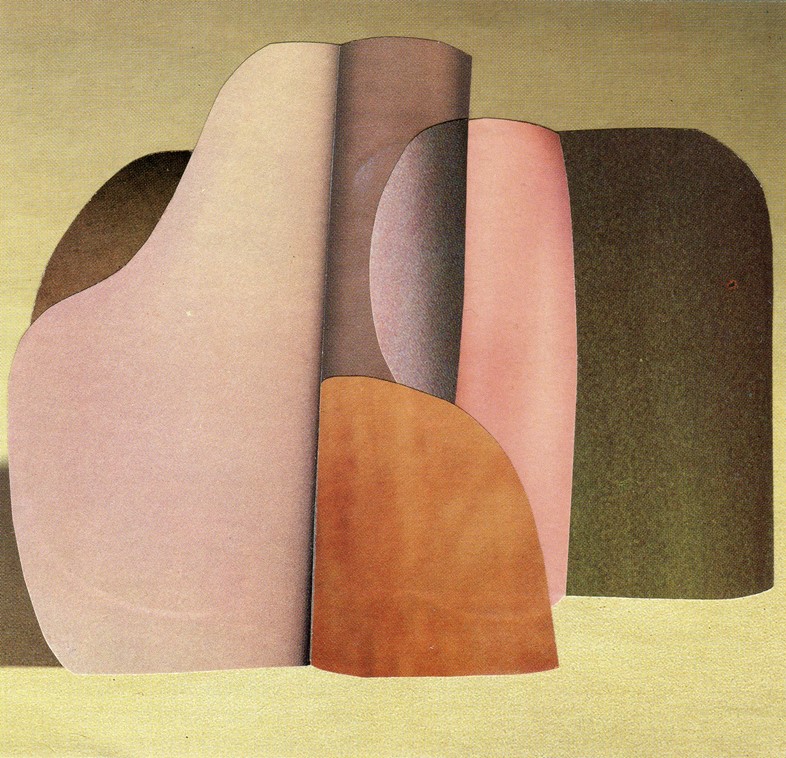

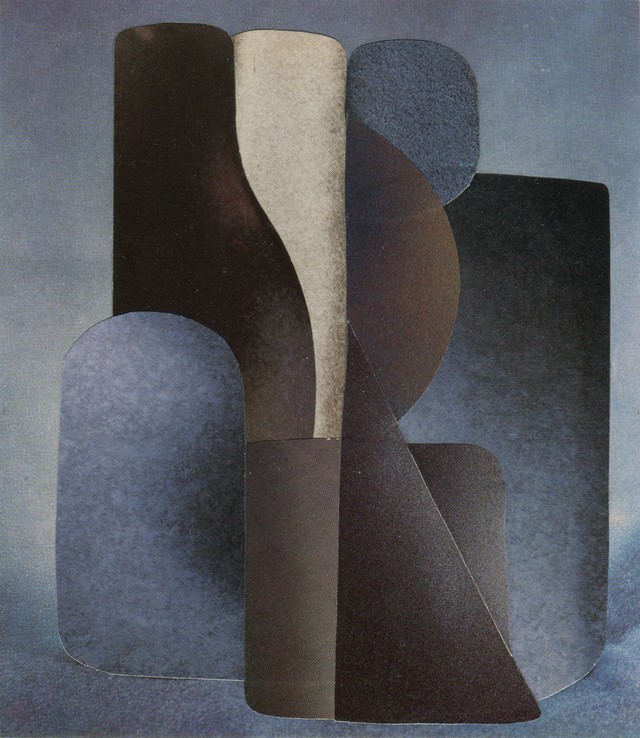

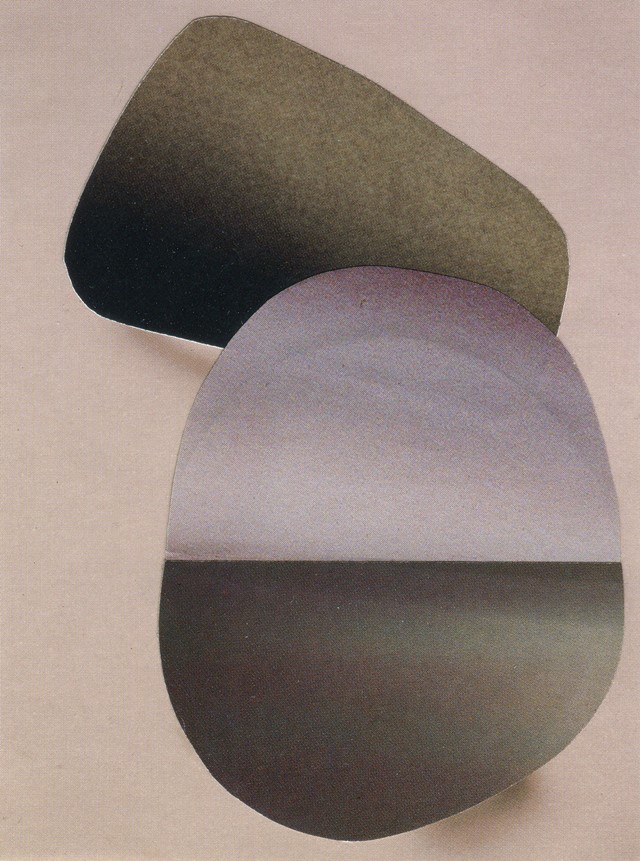

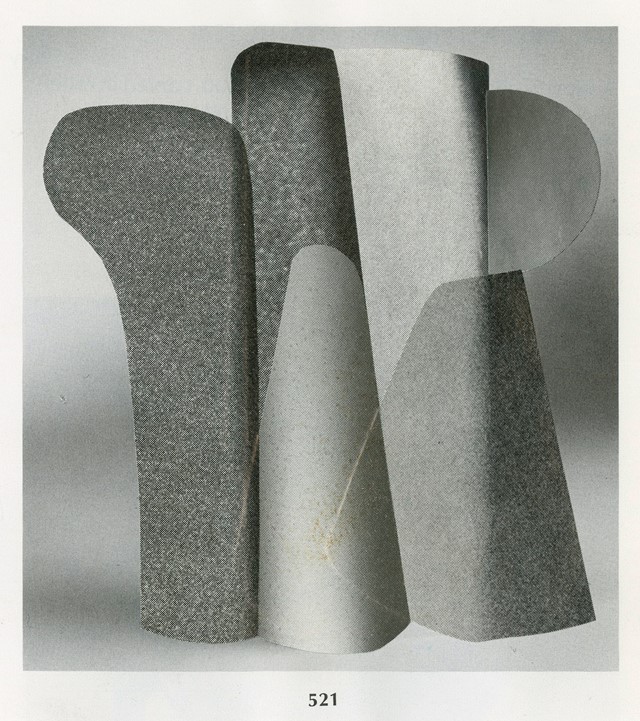

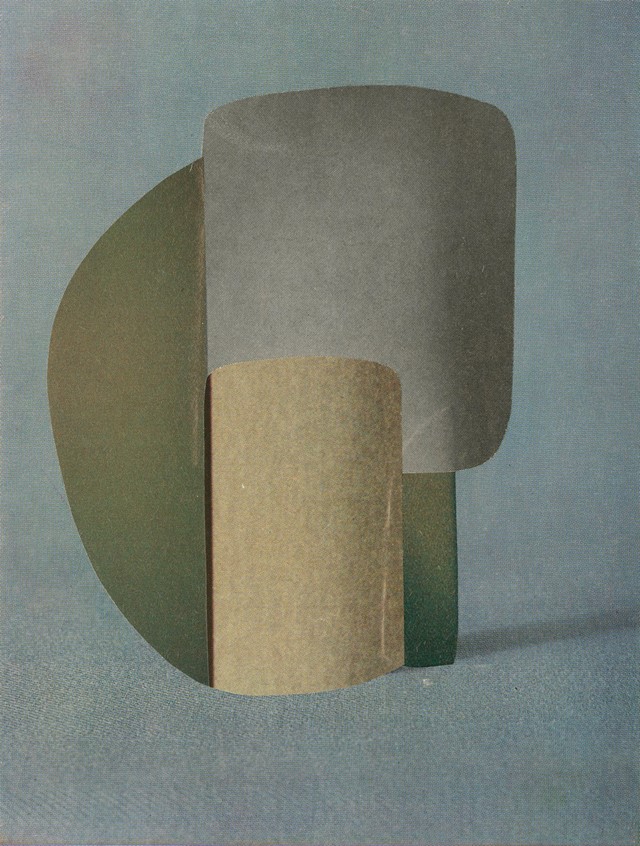

In Hannah Hughes’ series Flatlands, the “throwaway” sections from a vast array of archive images are transformed into pushing-and-pulling parts of new compositions – to radical effect

It’s no secret that artistic exercises can change the way that we see the world – and in the case of Hannah Hughes, this phenomena is deeply and pleasingly evident. Since 2014, the London-based artist has shifted her focus from painting to collage, in which form, by cutting out and inverting the negative spaces which surround objects and forms in catalogues, magazine shoots, photo journals and advertising imagery, she creates dynamic and lively compositions which both interrogate and reconfigure ideas about space and value. And perhaps as a result, she has become somewhat hyper-attuned to the negative spaces in the world around us in the process.

Now, a new exhibition at London’s Sid Motion Gallery places Hannah’s work alongside that of contemporaries Matthew Barnes and Abigail Hunt. The show, A Romance of Many Dimensions, takes its name from the subtitle of Edwin A. Abbott novella, Flatland (after which Hughes’ series is also named), and presents a nuanced new perspective on “two- and three-dimensional space and the tensions that are created by shifting between the flat and the sculptural; the photographic and the tangible; the man-made and the organic; the found and the constructed”. Here, Hughes tells us more.

On the archive materials from which she sources her shapes…

“A lot of the fragments I use come from vintage fashion magazines, auction catalogues: there will be, say, decorative ceramics, or objects of one kind or another that have been put up for auction, or are in a collection or display somewhere. I’m particularly interested in the auction catalogue as like a site of enquiry, partly because the backdrops in the older catalogues are always quite wonderful. I really love the ones where the photographer’s gone to town with an interesting textile backdrop, or an odd colour.

“But there are these negative spaces, spaces where things are moving in and out – they’re put into this non-space to be photographed, and then they’re going to be moved on and go through the auction and you don’t know where they’re going to end up. It’s a moment of transit, from one place to another. That sort of transition is interesting for me, formally and metaphorically.”

On inverting the value of negative spaces…

“The fragments I use to make these pieces are all negative spaces themselves. They’re the throw-away bits – apart from the fact that an old catalogue or an old magazine is out of circulation, and a bit throw-away in itself – it’s actually the spaces themselves, the unimportant sections of a photograph, that I focus on. Then they become the positive volume – they’ve been given pride of place in the image. So classifying them, categorising them, creating a sort of a language of their shapes [as the wallpaper in the exhibition does] is a kind of inversion of their value.”

On the active interplay between positive and negative spaces…

“Because they’re inverted, there are two types of volumes – positive and negative. They all come out of the shadows, but the way they sit together means that one shape will make the other look like it’s an inverse or a positive volume – so something recedes or something projects. Each piece plays with the other one, and pushes and pulls it, and they find their form together within that space. And that can keep shifting if you look at them.

“In that way, I think they retain a sort of active-ness, and that’s what I’m looking for when I make them – something that is not fully resolved. It’s an image that responds to the idea that things are constantly shifting and changing, that they come from different times and spaces, and that they have a language that makes them appear like an object that existed at some point in time, perhaps something sculptural or real. But that actually, it’s just made up of fragments, so they’re kind of denying or shaping each other.”

On recognising negative space in the world around us…

“I’m much more attuned to thinking about negative space around objects now. One of the very first moments when I started thinking about this series was when I had some images of [Constantin] Brâncuși’s studio in my studio. I was really obsessed with them, and I think what I was most interested in was this idea that he was basically moving these sculptures around all the time and trying to find the best placement for them, and the relationships between them, and then photographing them – but for me it was all about the fact that he was making spaces between them. There was a real, radical use of light, so that he was referencing the space around what he’d made. I think I’m always searching out the opposite thing to what you’re supposed to be looking at.”

On the resonance of the series’ namesake – Edwin A. Abbott’s Victorian novella, Flatland...

“It’s that classic art school idea: when you’re training, try and look at the other thing, outside of the main subject – it’s about a way of relating spaces to each other, to think about things in space. And obviously that’s what this series is referring to in the title, Flatland, which is the Edwin Abbott novella, the journey of the square basically into space. I mean, that novella is talking about Victorian society as much as it is about the possibility of a fourth dimension. It’s about how difficult it is to see beyond the set of parameters that we set up for ourselves. I think that as soon as you start to invert things, even in the form of abstraction, it sets up a bunch of questions about our capacity to create change, and to imagine beyond our pre-existing parameters. I’m interested in the idea of creating new languages from pre-existing forms as a completely alternative way of seeing what’s around you.”

A Romance of Many Dimensions runs until September 22, 2018, at Sid Motion Gallery, London.