The German-Ghanaian artist powerfully meshes photography and fabric to investigate the connections between codes of dress and culture

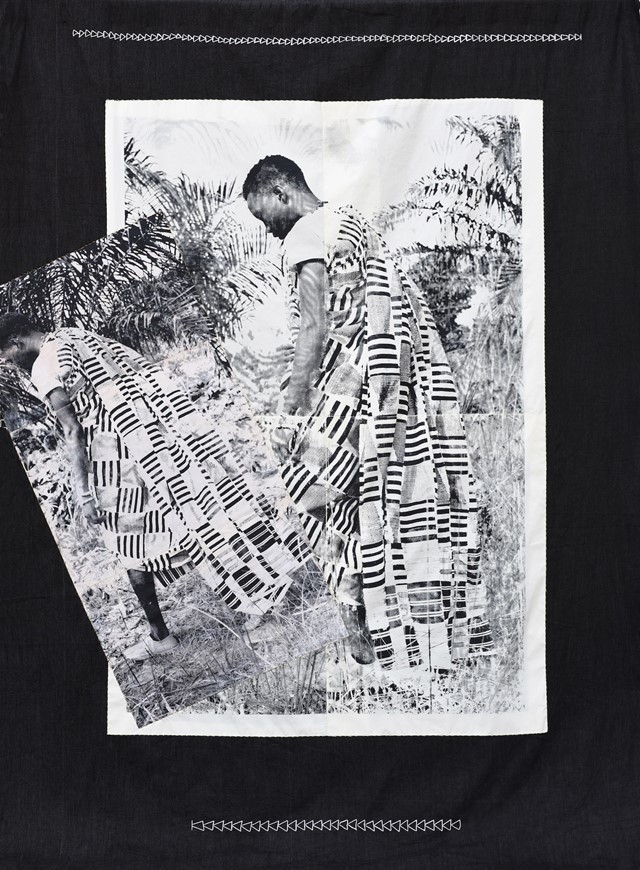

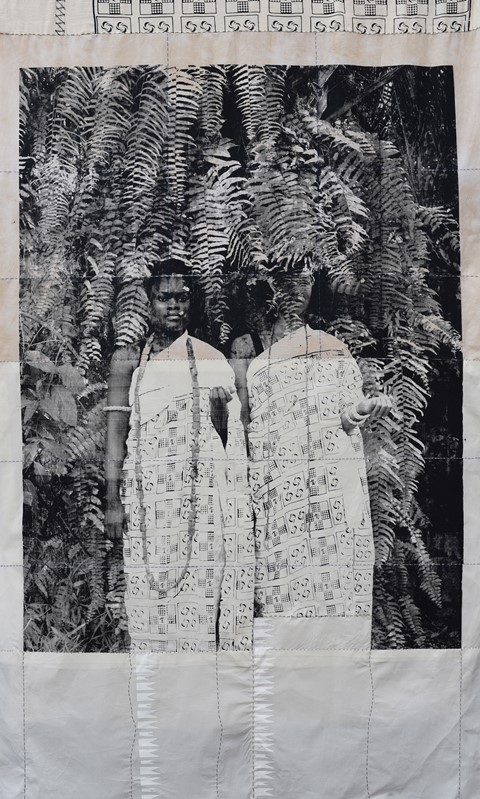

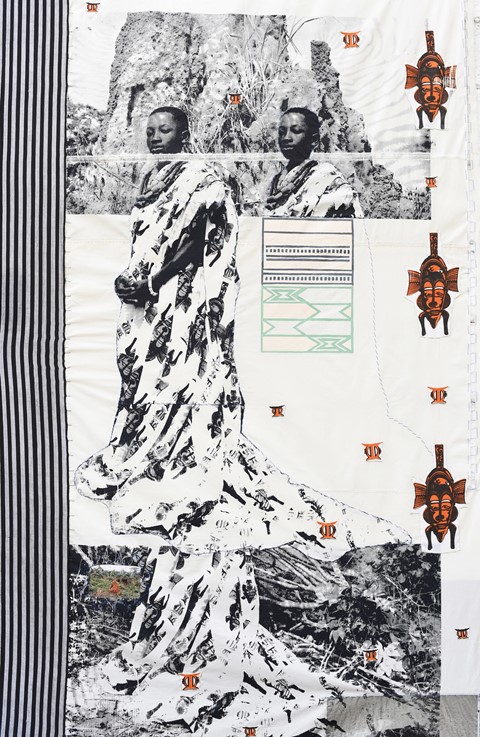

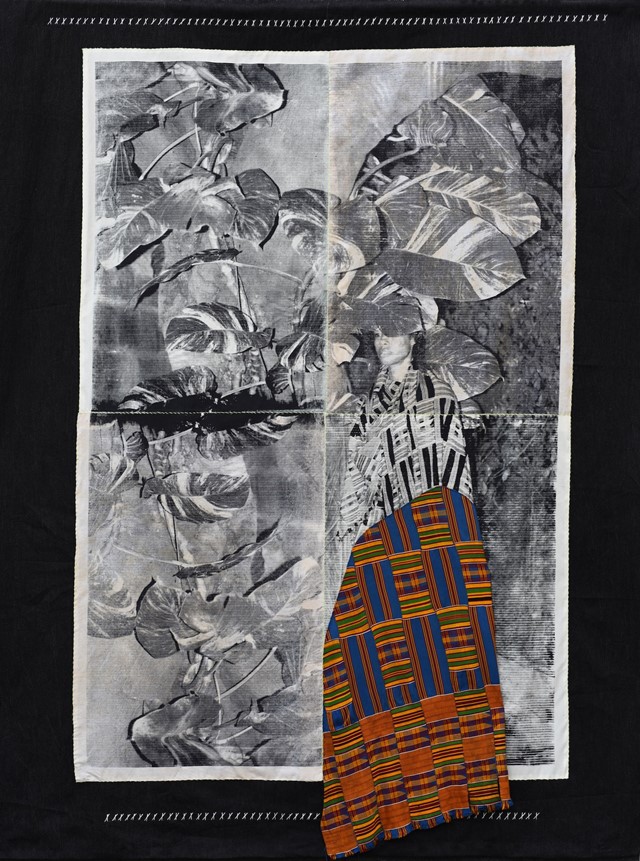

On a quiet street in Ghana, the bumpy road gives way to a luscious garden complete with trailing, fragrant foliage that somewhat obscures the entrance to Zohra Opoku’s home-cum-studio. The German-Ghanaian artist has lived here for several years, save for a few international residencies, and the ground floor is full of enormous screens used to produce her large-scale textile images, many of which hang from the walls. “I need to get a bigger space,” she sighs. “I don’t have enough room to work on more than one thing at a time.” At present, an enormous textile hangs in the front room. It depicts her siblings dressed in traditional clothing and comprises of smaller prints that have been transferred onto cloth supplied by her grandmother, before being stitched together with green thread given by her mother. For her, this is about building a ‘collective memory’ that draws on her family history and wider investigations into cultural identity, particularly through codes of dress.

Opoku originally studied fashion, so the interest has always been prevalent, but she was quickly seduced by more experimental processes that spanned across photography, printmaking and drawing. “I snuck into the darkroom,” she explains. “I wasn’t allowed in as I was not part of the photography course, but luckily I befriended the advisors. Later I started to do crossover courses, where I was incorporating photography into fabric works.”

The significance of textiles permeates Opoku’s practice. Her prints are produced on second-hand cloth that gives a rougher, organic texture than what she refers to as “stiff and inflexible” paper, and the appearance of Kente cloth – both as a raw material and depicted in her portraits – directly references images of her late father and other symbolic nods to her Ghanaian ancestry.

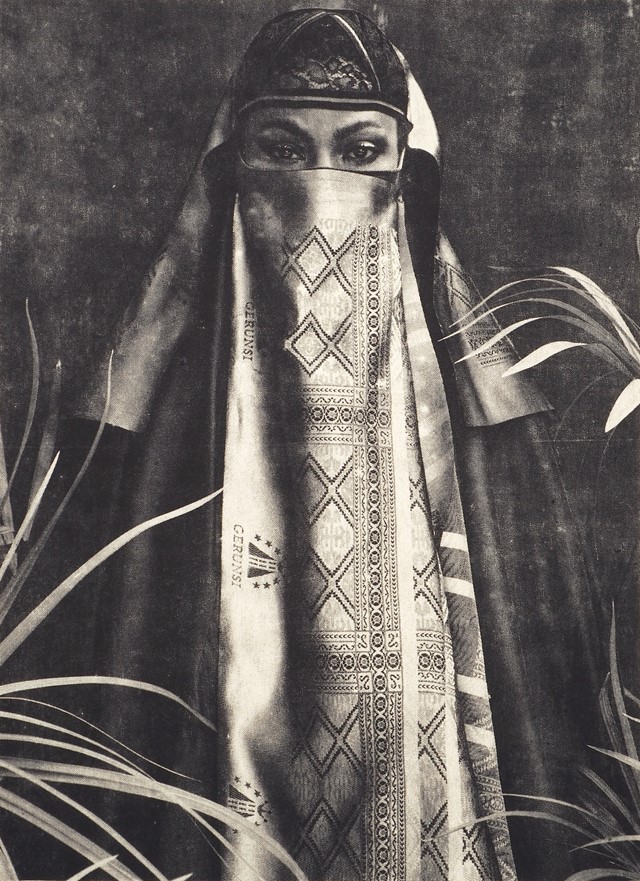

Her interest in the cultural significance of garments also stretches way beyond her own family heritage. In her Harmattan Tales series Opoku spent time with Muslim women in the UAE and in Ghana to explore different interpretations of the veil. The results are a stunning collection of pieces that look as if they could have been plucked from a transient memory or discovered among a forgotten box of studio portraits. The images are overprinted and re-stitched, some with additional physical adornments or great sweeping brushstrokes. Opoku also modelled more experimental investigations of modest dress, many of which use translucent lace to create somewhat unsettling interpretations that are undeniably alluring.

For Opoku, this process was about moving beyond the distant assumptions that are prescribed for women who wear the veil and attempt to truly understand the comfort and conflicts that come with this particular form of dress. “Here in Ghana Islam is very positively connected and integrated into daily life, it’s not a conflict like in other countries,” says Opoku – a fact that has made the project far more multi-faceted. “In this ‘Trump’ era, we really need to consider what our judgements are based on when we look at a veiled woman,” she continues. “What does it really move in ourselves? I have lived experiences in Germany with the Turkish community, here in Ghana, and I also spent time in Senegal… it’s different everywhere.”

This desire to connect to a genuine lived experience resonates throughout all of her work, and when asked about how she selects the individuals to pose for her portraits (including her own powerful presence) she takes a broader view. “I don’t think of the individuals or myself as a model, I’d rather think about presenting a society. I have a lot of sisters in Germany who are in the same position as me and although they are not in Africa they share the same histories, and there are a lot of other Afro-Germans over there, due to immigration in the 1970s. There is this sentiment of having this particular background but not really understanding where you’re from. It applies in so many different ways and in so many places around the world. Nowadays everything has become a lot more connected and globalised. Dual citizens, family members moving to other places, or people escaping to different countries – it has become the standard now.”