Take a closer look at the Barbican Art Gallery’s unforgettable new exhibition about counterculture

Barbican Art GalleryIn her oft-referenced 1977 book On Photography, a collection of essays deconstructing the political and cultural relevance of the photographic medium, Susan Sontag describes Diane Arbus’ raw, unflinching gaze as “based on distance, on privilege, on a feeling that what the viewer is asked to look at is really other”. Sure enough, Arbus was obsessed by otherness – she spent her life documenting the outcast, the misfits and the rejected on the fringes of society. Yet her jarring, unsettling portraits are nothing short of quietly luminous visual reservoirs of frozen humanity. Not only do they not feel detached or exploitative of their subjects, they convey a deep sense of intimacy, collaboration and dialogue.

Nearly five decades after the pioneering image-maker’s untimely death, her work retains every bit of its aura, and her game-changing legacy is as contemporary as ever. The Barbican Art Gallery’s latest exhibition, Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins is a testament to trailblazers such as Arbus, who used the transgressive nature of their medium to shine a light on outsider communities through emotional engagement and understanding rather than simple observation. “Photographers often see themselves as outsiders, and the camera gives them access into these worlds that they wouldn’t usually be able to access,” explains curator Alona Pardo. “It’s interesting how our attitudes to gender, sexuality, subculture and the multiplicity of society change, and how photography has helped shape that. The aim of this show was to remind people of how photography has contributed to this discussion about difference and trying to affirm your own identity.”

Ahead of the exhibition opening, we speak to Pardo about some of the most poignant examples of photographers who crossed the line from the outside to the inside, gaining unfettered access into the shunned beauty, tenderness and brutality of alternative communities.

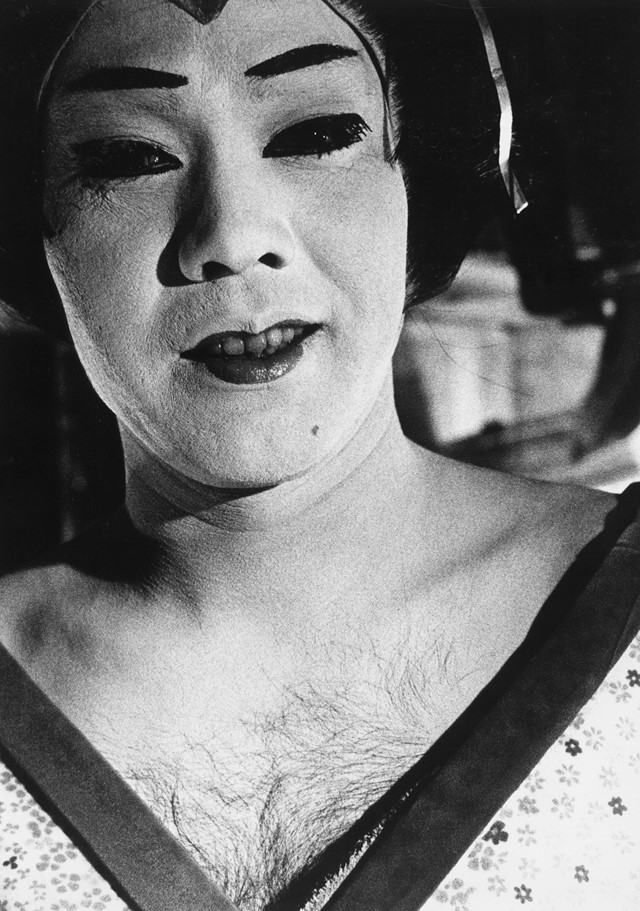

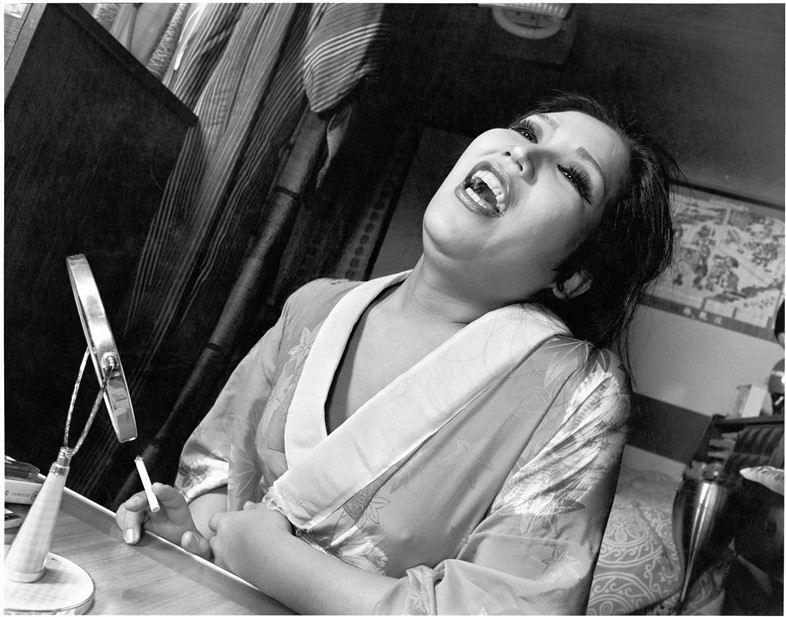

1. Daido Moriyama

“In the mid-1960s, the self-taught Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama turned to the back streets and dark interiors of dressing rooms and small stages in the districts of Asakusa – famous for its underworld and theatrical tradition – and Shinjuku. Driven by the pursuit of reality, his black and white, grainy, out-of-focus images homed in on gangsters, nightclub entertainers and sex workers to create a steamy portrait of Tokyo.

Moriyama embraced the erotic and chaotic elements of society. In Japan: A Photo Theatre, published in 1968, he expanded his earlier series Entertainers to combine surreal imagery of theatrical figures with urban outsiders. Prowling Tokyo’s narrow streets, Moriyama photographed the city’s vernacular nightlife: strip joints, gangster bars and backstreet Kabuki theatres. Upon the invitation of the enfant terrible of Japanese culture, Shuji Terayama, whose avant-garde theatre group Tenjo Sajiki was comprised of members from the margins of society, Moriyama documented nude women, actors of short stature and burlesque characters of all kinds.”

2. Seiji Kurata

“Following in the footsteps of the celebrated American news photographer Weegee, who installed a police radio in his car in 1938, Kurata trailed the police and the world of gang fights, yakuza, motorcycle boys and motorcycle deaths. Armed with his Pentax 6x7 and a flash, Kurata immersed himself in the underworld of Ikebukuo and Shinjuku and his book Flash Up, published in 1980, involves a descent into Tokyo’s underground network of clans. In the midst of one of the safest cities, in a society that was viewed as one of the most conformist, Kurata introduces a cast of tattooed gangsters, right-wing activists, leather-boys, bargirls and an emerging queer community that countered the perception of Japan as a beacon of social conformity and repression.”

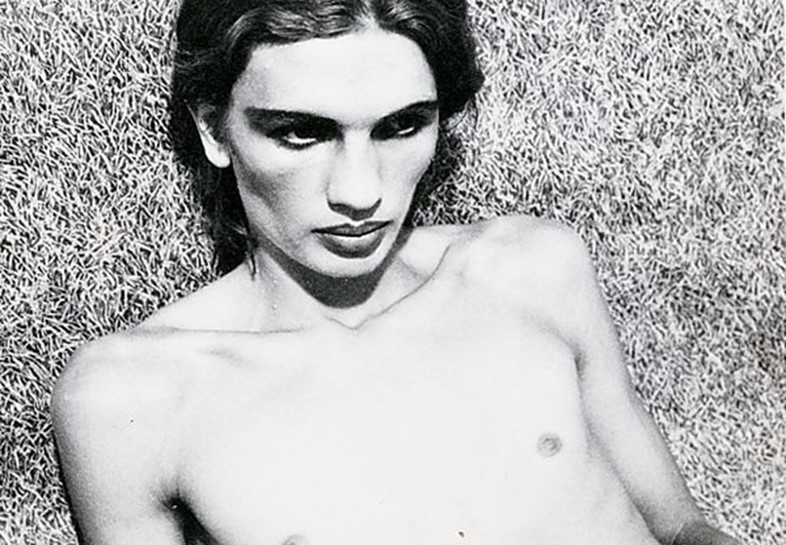

3. Walter Pfeiffer

“Over the course of a number of months in 1973, the Swiss artist Walter Pfeiffer made a set of photographs of his then muse Carlo Joh. They charted, across black and white images, a young man in differing states of gendered appearance, oscillating between naked, made-up and in drag. Pfeiffer recalls that the sequence ‘started with Carlo Joh in his blossom and beauty, and every time he came – we photographed maybe once a month – he got thinner, and you see this in the pictures’. The compulsion to document was shared by the subject, as Carlo Joh brought lamps and a camera to every session and did his own make-up. Pfeiffer in return made the framing for each photo and directed the sittings in his apartment. Carlo Joh died prematurely soon after the photo sessions ended.”

4. Teresa Margolles

“The specificity of the Latin American context is explored in Teresa Margolles’s powerful series Pista de baile (Dance Floors; 2016), which exposes the precarious economic position of transgender sex workers in the Mexican border town of Ciudad Juárez. Standing tall and proud under the beating sun and set against a vivid blue sky on the remnants of the dance floors in the nightclubs they frequented, the individuals documented here have been excluded from the social order first for their gender and then for the only profession open to them, prostitution. Subject to continued violence, Margolles’s figures become part of a landscape in which ruin and devastation are the main protagonists. Despite this, the sex workers show their best face, as if reaffirming their presence in the midst of violence and destruction.”

5. Katy Grannan

“After moving to California in 2006, the American photographer Katy Grannan has sought to photograph ‘new pioneers’, people who – much like her – had encountered something quite different from the mythological West, with its promise of constant sunshine and the potential to fulfil the American Dream. Grannan’s 2011 series Boulevard was conducted over three years on the streets of the Tenderloin District, in San Francisco, and Hollywood Boulevard, in LA. Placing individuals against sun-bleached white walls and shooting at midday, the strong sunshine transforms the city streets into outdoor studios. These images present the subjects as both heroic and vulnerable, drawing the viewer’s attention to these often invisible figures.”

6. Boris Mikhailov

“Challenging and provocative, the photographs of Ukrainian image-maker Boris Mikhailov document the suffering of individuals living in post-communist Eastern Europe after the demise of the Soviet Union. They offer unflinching depictions of poverty and the homeless (also known as Bomzhes) living on the margins of Russia’s new economic regime. Following on from his critically acclaimed series Case History (1997–98), in which Mikhailov photographed homeless people in his native town Kharkov, The Wedding (2005–06) presents a fictional marriage between two Bomzhes. With their harsh realism and wry humour, Mikhailov’s photographs of these nearly naked figures taken in their personal surroundings, are designed to evoke feelings of empathy and disquiet.”

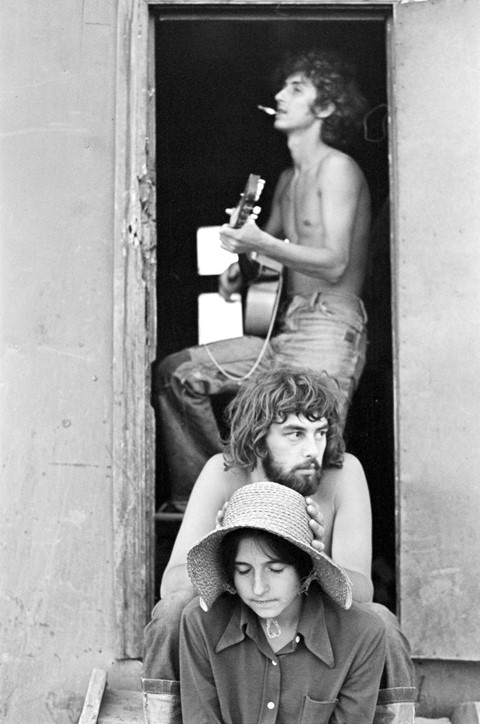

7. Igor Palmin

“Russian photographer Igor Palmin’s series The Enchanted Wanderer, 1977, was shot on an archaeological expedition in southern Russia and contrasts a countercultural youth – sporting long wavy hair, hairband and bell bottoms – against the desolate environment of the socialist economy of the former Soviet Union. Organised by universities, archaeological digs were a popular vehicle for bohemians to escape, if only temporarily, from the city and the controlling gaze of the authorities.

The central figure in Palmin’s The Enchanted Wanderer – a title taken from the 19th-century novel by Nikolai Leskov, in wide circulation among the underground – is Sergei Bolshakov who can be seen traversing the surreal landscape of the Russian steppe. Shot in one afternoon, the photographs’ grainy cinematic quality lend the work an abstract dimension and can be attributed to the poor quality of materials available in the Soviet Union at the time. Typical of much of the Soviet hippie community Bolshakov came from a privileged background and embraced the idea of hippiedom as a meaningful alternative to Soviet life. They believed themselves to be anti-Soviet: that meant they were opposed to Soviet ideology, lived a non-Soviet life and rejected the existence of a Soviet person.”

Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins runs from February 28 until May 27 2018, at the Barbican Art Gallery, London.