The Cult Of Beauty at the V&A brings together visionary works that fundamentally changed the game in art at the dawn of the 20th century. Curated by Stephen Calloway it explores the chief protagonists of the aesthetic movement, radically-minded

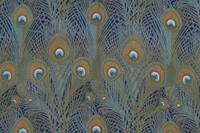

The Cult Of Beauty at the V&A brings together visionary works that fundamentally changed the game in art at the dawn of the 20th century. Curated by Stephen Calloway it explores the chief protagonists of the aesthetic movement, radically-minded individuals heavily influenced by the romantic poetry of Keats and Shelley who were firm advocates of the belief that beauty is, above all else, the only thing worth aspiring to, or indeed to live for, and that art should exist purely for its own sake. The movement exploded across art and literature in the late-1860s, with its charmingly caustic celebrity mouthpiece Oscar Wilde leading the charge on the stuffy moral status quo that had defined 19th century. However, the aesthetics were quickly lampooned for their foppish, languorous self-image and received wisdom has it that the movement had imploded into absurdity by 1880. However, Calloway would argue that it became even more interesting over the next two decades, descending quietly into a morbid decadence, with some of its leading lights hopelessly addicted to opiates and increasingly fascinated with the macabre. Here, he tells AnOther why their doomed quest for perfection might just have paved the way for the grotesque excesses of our modern agent provocateurs.

In what sense did the aesthetic movement mark a profound break with more traditional art?

The essence of what I think the aesthetics were trying to get away from was the idea that art was about anything else. The idea was simply to be beautiful. If you look at a predecessor, such as the vanitas tradition, it’s really about a moral, it has a sense that there is something beyond visual beauty; that there’s actually a moral dimension to art. What is fundamentally different about the aesthetics is that they were trying to get away from the association of art with moral or religious sentiment. They were vaguely aware of Baudelaire and were very taken with the ideal that art could be about nothing at all.

How much impact did the aesthetic movement have and where can we see its influence in modern art?

Well, it’s almost impossible to see a direct influence but if you think about the movement in terms of how art is now understood or the position that art fought to hold, then the ideas in the aesthetic movement are fundamental. We think that art is very important now and people regard it incredibly highly – art is probably more important than religion these days. This idea has its origins in the way people thought in the 1860s and 70s. It’s the birth of this notion about the importance of art and the importance of the response to art – the idea that you define your own individuality by your response to works of art.

It seems very much like a movement committed to celebrating the outsider…

There’s a distinct suggestion of that, and some figures more than others certainly cast themselves deliberately as outsiders. It’s conventional to say that they were bohemian but that’s only part of the story. I think they classed themselves intellectually as outsiders and wanted to be outside the normal system. Lots of the artists managed to strike quite a novel balancing when dealing with the world, but amongst themselves, they did see themselves as rebellious figures.

There is this morbidity in much of the work, does that come from an intrinsic notion that beauty is essentially unattainable or fleeting in nature?

There may well be something in that. It’s no accident that such an extraordinary number of the images are somehow languid. If you actually decide that beauty is about only itself and that it’s not leading to anything then where does it go? I think that is the central question and I think there is certainly something slightly sickly at the core of it. There is the feeling that it all ends in decadence and that’s part of what we wanted to explore in this show. I’ve always been really interested in this idea of what we call the decadent 1890s. At that point, there is a distinct feeling that everything is rushing towards decadence and this idea that there’s actually beauty in ugliness.

There is certainly that sense of the macabre framing beauty. Do you think there is a line to be drawn to the contemporary works of say, The Chapmans?

That’s really interesting. Some of those people working today, for the most part, know don’t necessarily know a great deal about some of the artists that are in this show and wouldn’t perhaps immediately see affinities but I think connections can be made. I think that there is a line, as it were, from the more decadent side of the 1880s. Rosettti, for example, became much a recluse towards the end of his life, surrounding himself with really bizarre things. It’s very likely that the opium derivatives he was addicted to induced visions, which come through in his extraordinary late pictures. I think there’s a distinct sense of a growing interest in the macabre and even in the extremely grotesque, and sometimes you do sort of strike the sense with certain characters that they almost took delight in shocking, which would bring you quite close to The Chapmans.

There’s also this notion of democratic beauty at the core of the movement. That seems like quite a revolutionary strand…

That’s sort of the great dilemma at the heart of everything William Morris does. In the later years, he starts saying things like "I didn’t want beauty for a few any more than I want education or freedom for a few", but, of course the contradiction is that the things he makes are very expensive and therefore can’t be made for everyone. He wrestled with that right through until his last years. There’s certainly a strand of the movement that is about that sort of idealism – making beautiful things available to everyone, and that creating beauty improves the lot of everyone, perhaps slightly intangibly. But at the same time, we also have to admit that there was a very real ivory tower, an elite side that was about people who just wanted to just shut themselves off from what was seen as the ugliness of ordinary life.

The Cult Of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement runs at The Victoria And Albert Museum until 17 July