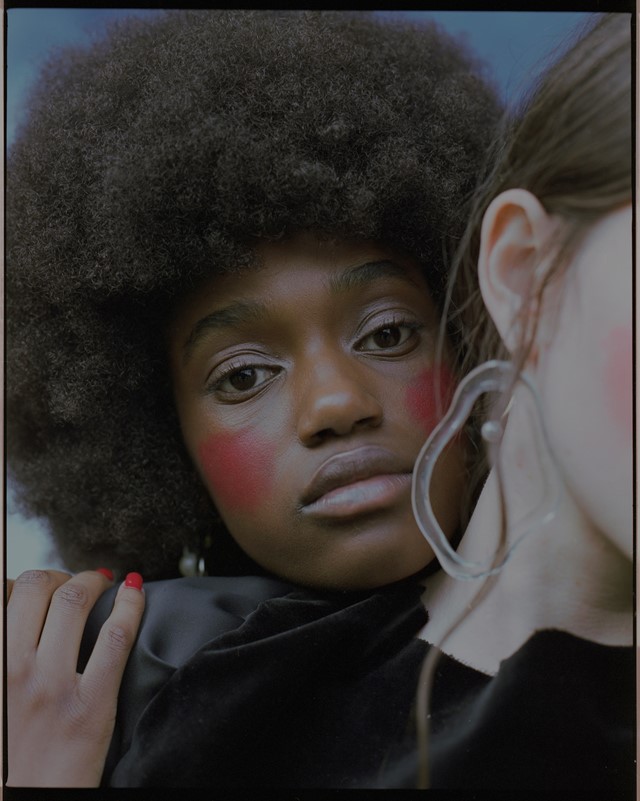

From disrupting gender norms to eliminating tokenism, Nadine Ijewere is passionate about bringing different notions of beauty to fashion photography

Storytelling and fantasy form the backbone of fashion editorial photography, but the medium is also rooted in narratives of oppressive favouritism. Numerous versions of whiteness have been presented by fashion campaigns and imagery over time, while people of colour are often relegated to perform as tropes and symbols. Frequently, these symbols are then co-opted as additional versions of whiteness. Photographer Nadine Ijewere is constantly thinking about disrupting these norms, whether through casting diverse models or turning to her community in Lagos for collaboration on major projects.

London-based Ijewere has made her mark in the fashion industry with a series of subversive campaigns, from her #StellaBy Nadine Ijewere project for design powerhouse Stella McCartney, to her most recent project 9-ja_17, a collaboration with stylist Ibrahim Kamara that depicts Nigeria’s underrepresented younger generation. We chatted with her about the fine line between reclamation and appropriation, and why it’s important to represent different standards of beauty.

On how her fascination with fashion imagery began…

“I think what always drew me to editorial stories was the concept of communicating an idea through an image, because I’ve always related more to images than text. What I like about fashion editorials in particular is that you can mix both imagery and clothing, and if you are trying to bring forward an idea or point, you can actually use fashion to elevate it. Especially when I go somewhere like Nigeria or Ghana, I can incorporate fashion into my images so it isn’t just a straight documentary project or simple fashion shoot. Instead, I combine the two so that I fall somewhere in the middle.”

On addressing cultural appropriation through fashion photography…

“I love casting people from different backgrounds and ethnicities, those who aren’t the standard in the fashion industry, but when it’s a commercial project I don’t bring certain traditions, ways of dressing or customs into the work. There’s a very fine line between reclamation and appropriation, and I don’t want to regurgitate the same things that previous photographers throughout the history of fashion have done. But within my personal work, I specifically explore countries and identities that relate to me. It’s something that I’m constantly aware of throughout each project.”

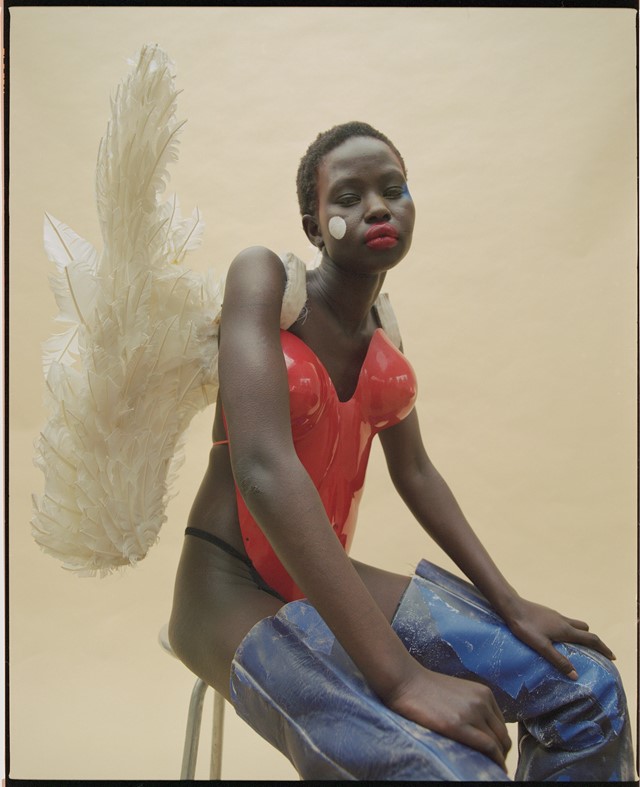

On creating 9-ja_17 with stylist Ibrahim Kamara…

“Ib and I have been friends for a long time, and he’s able to focus on blurring the line between what’s masculine and feminine, showing that men don’t have to be presented in a certain way. There are different ways of representing beauty in fashion and we don’t have to stick to the rules. Ib will have random objects and put together an outfit on the spot, so I consider him to be more of an artist than a stylist. We’re both passionate about celebrating our culture and a new type of beauty, and exposing countries in Africa to a wider audience. Everyone has this specific perception of Africa, and we want to get rid of those stereotypes and show that the younger generation is very passionate.”

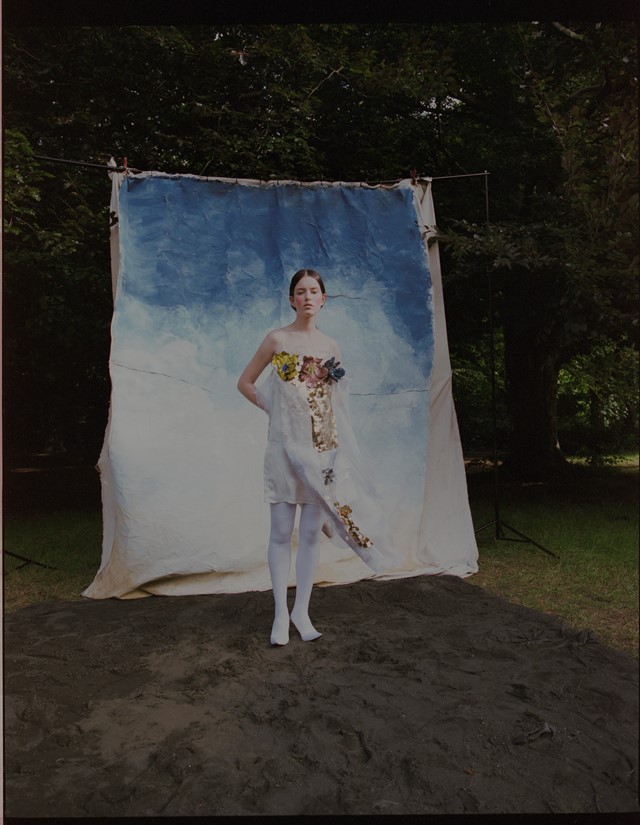

On the importance of shooting for Stella McCartney in Lagos...

“I was approached by Stella McCartney to do the #StellaBy project, and I initially thought I would shoot it in the UK. But when I thought a bit more about having a budget without restrictions, I liked the idea of bringing a big brand to where I’m from to give back to my community. I wanted to work with hair and make-up people based in Lagos, and do street casting while working with local videographers. A brand like Stella McCartney has a certain look, and doing something completely different from what they have done in the past appealed to me. I decided to take the womenswear collection and dress men in it, mixing fabrics from the local markets with the designer pieces so that it all to related to Nigeria. It was great because it wasn’t just a standard advertorial piece, and had my country and community woven throughout.”