This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale now. Order here.

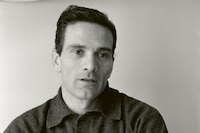

Filologia minima – minimal philology – is how Franco Zabagli (born, 1959) describes his analytical approach as a literary critic and scholar. In order to give illuminations on an author or artist, Zabagli prefers to focus on unexpected clashes, little fractures, his eye drawn to small details, ephemera and contradictions; to finding meaning in what’s often overlooked or considered of secondary relevance. Pier Paolo Pasolini, of whom Zabagli curates the archive at Gabinetto Vieusseux in Florence – considered the world’s largest collection of Pasolini’s belongings, sketches and written work – is central to his research. Zabagli has written several essays on Italian literature, particularly on Leopardi, Pascoli, Montale, and Pasolini. He edited the volume Pier Paolo Pasolini: Paintings and Drawings, and the two-volume essay Per il cinema di Pier Paolo Pasolini together with Walter Siti.

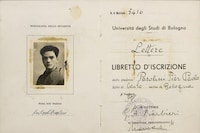

My collaboration with Gabinetto Vieusseux began in 1986. As a recent graduate, I was given several research assignments on the archives of this prestigious Florentine institution, where a Contemporary Archive had been established about ten years earlier by director Alessandro Bonsanti to collect materials belonging to major literary figures of the twentieth century. The Fondo Pasolini was entrusted to the Contemporary Archive in 1988 by Graziella Chiarcossi, (Pasolini’s) cousin and heir, and by chance the task of organizing and cataloging those materials was entrusted to me. Pasolini had long been a poet and filmmaker whom I greatly admired and whose civil battle and harsh, desperate ideas about “anthropological mutation” and the disastrous effects of acculturation brought on by neocapitalist consumerism had deeply impressed me. I have thus dedicated most of my scholarly work to him. Being able to work directly with his papers has been one of the happiest experiences in my life.

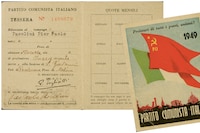

The Fondo Pasolini held in Florence is vast and encompasses almost the entirety of his “laboratory” (as he himself called it). Other collections of papers are held at the Casarsa Study Center, the National Library of Rome, and the Manuscript Center of the University of Pavia. The transfer of the materials to Florence began in 1988 and was completed within a few years. Graziella Chiarcossi was its first impeccable archivist, and the documents that gradually arrived at the Archive were already organized by categories (letters, poems, narrative prose, screenplays, newspaper articles, essays, press clippings, etc.) which greatly facilitated my work. Graziella remains a valuable resource because she herself was a direct collaborator to Pasolini, and her memory preserves information that no one else would be able to provide.

In Pasolini, genres and media intertwine while everything contributes to create a single, multifaceted whole. “Poetry” is certainly the primary element, as Pasolini’s identity is, and remains, that of a poet: his profound ties to the Italian literary tradition, coupled with his brave experimental urge, require us to understand the term “poetry” in a renewed and complex way. Pasolini, as he famously said of himself, was “a force of the Past,” but also “more modern than anyone modern.” Once he had devoted himself to cinema he theorized in highly complex essays his formal idea of a “cinema of poetry.” The plans for Petrolio, his last eponymous book, envisioned multiple techniques, styles, and materials: this was a novel already conceived as a “multimedia” opus in years when “multimedia” as a concept was not widely explored in Italy. What takes Pasolini apart from contemporary experimentalism, however, is his culture, which stemmed from multifaceted interests, and a solid, constantly updated knowledge, combined with an interpretive acumen that he could formidably apply to aesthetic, literary, anthropological, and political matters. This variety of expressive forms is reflected in the archive. The only poet I can think of who, like Pasolini, so significantly explored a variety of media, including painting and film, is perhaps Jean Cocteau. Both strikingly define the new sociology of the twentieth-century literary man that emerged in the postwar era, especially in regards to cultural work related to new ways of production and media exposure.

“Pasolini’s identity is, and remains, that of a poet” – Franco Zabagli

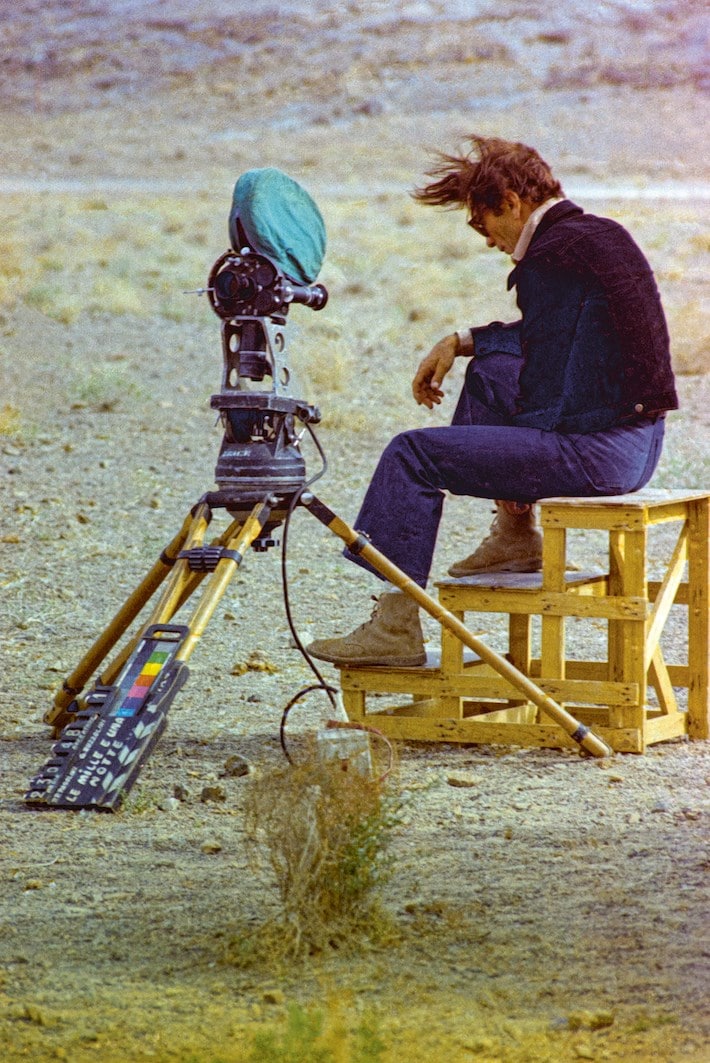

Pasolini, as an artist, was hugely interested in self-representation. His perception of reality, as expressed in his work, was always powerfully subjective, refracted through the reflections of his consciousness and the phenomenology of his own eroticism: many of his poems are “self-portraits,” and the self-portrait is a recurring subject in his paintings. When his work as a poet was supplemented by his experience in filmmaking, new opportunities for self-representation arose, such as those in The Decameron or The Canterbury Tales, where Pasolini took emblematic roles for himself. Experiences like those documented in Pedriali’s photographs, or those undertaken with his friend, the artist Fabio Mauri (with the projection of Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo on Pasolini’s body), can be legitimately labelled as performance art.

Pasolini’s fame, nowadays, is global. When thinking about it, I always recall that it all began in 1942 with a small book of poems written in a dialect spoken in a small town in northeastern Italy. The disproportion between the premises and the effects is unimaginable. From the rural microcosm where he emerged as a poet, Pasolini tirelessly continued to explore the world with the same gaze, seeking the authenticity and sacredness of life among the humble, among the people of the impoverished suburbs of 1950s Rome, in the southern Italian towns that had resisted “homogenization” for the longest time. Then, as the past was rapidly replaced by a reckless and purely consumerist development, he pushed his explorations to Africa, the East, and South America, recognizing everywhere a phenomenon of “anthropological mutation” that was irreversible. Although Pasolini’s fame is often vague and distorted, and tied more to the sensational aspects of his biography than to a true knowledge of his work, I believe that we perceive in him the symbol of something essential that has disappeared from the world, and that we sorely miss.

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale now. Order here.