This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale now. Order here.

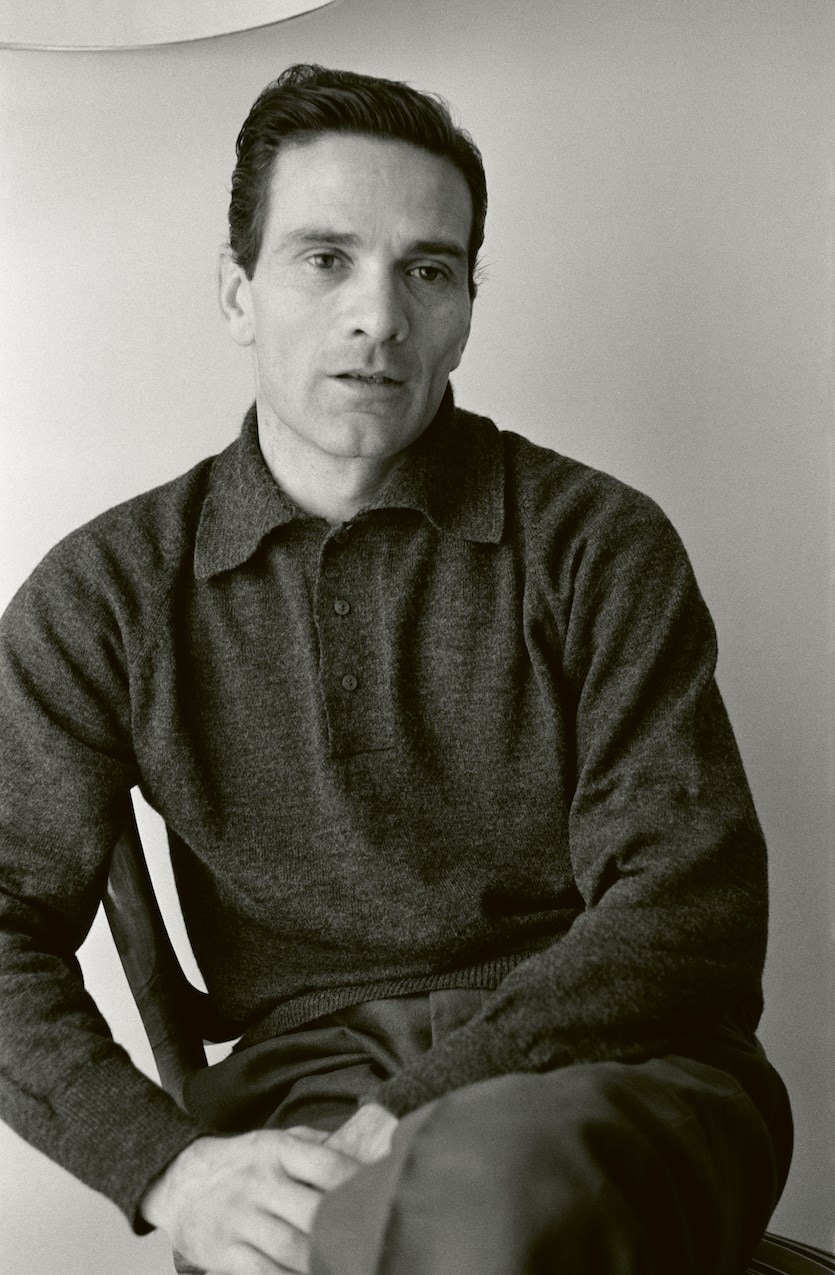

“Those few who’ve shaped history, are the ones who’ve said ‘no’...” Pier Paolo Pasolini said in an interview a few hours before he was murdered. “As a person, I do pay for what I say... Maybe I’m wrong after all, but I keep on thinking that we are all in danger.”

Fifty years ago this November 2, Pasolini’s body was found on a soccer field in Ostia, a working class suburb on the outskirts of Rome. The details are probably as well known as any of his films. He had been run over multiple times by his own Alfa-Romeo. His face was so badly disfigured he couldn’t be immediately identified. His testicles had been crushed and his clothes were singed, evidence of an attempt to light him on fire. He was fifty-three years old, a national celebrity, and his body appeared on the cover of the Italian tabloids, mobbed by local gawkers being held back by cops.

The details are still murky. A seventeen-year-old “rent boy” confessed. After serving nine years, he claimed he was intimidated into taking the rap to protect his family. The court agreed that more than one assailant was certainly involved. The case has been reopened and shut down in court over and over. Was it an anti-gay hate crime, as the tabloids claimed? Was it the neo-fascists or government elites Pasolini railed against in his newspaper editorials? Was it the corrupt oil baron he’d been writing a book about? Was it a botched attempt at recovering stolen reels from the production of Saló? Was it self-orchestrated, a suicide disguised as murder: a deranged final artwork?

The murder has inspired as much mythology as conjecture. Kathy Acker fictionalized it in her novel, My Death My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini (1988), a first-person chronicle of Pasolini trying to solve his own murder. Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini (2014) traces the final day of his life, imagining a last blow-job and the deadly beatdown itself. William Kentridge’s charcoal drawing of Pasolini’s corpse, Death of Pasolini (2014), was blown up as a mural on the banks of Rome’s Tiber river in 2016 – alongside the god Remus and Saint Theresa. In 2021, John Waters embarked on a pilgrimage to the location of Pasolini’s fall, his feelings recorded as voice notes and released as a spoken word album, Prayer to Pasolini. Waters finds the area fenced-off, but the padlock is miraculously unfastened. He gets on his knees and speaks in tongues into the microphone, comparing the site to the Stations of the Cross. As part of Conor Donlon’s retrospective for this issue, J.H. Engström documents it like he’s collecting forensic evidence.

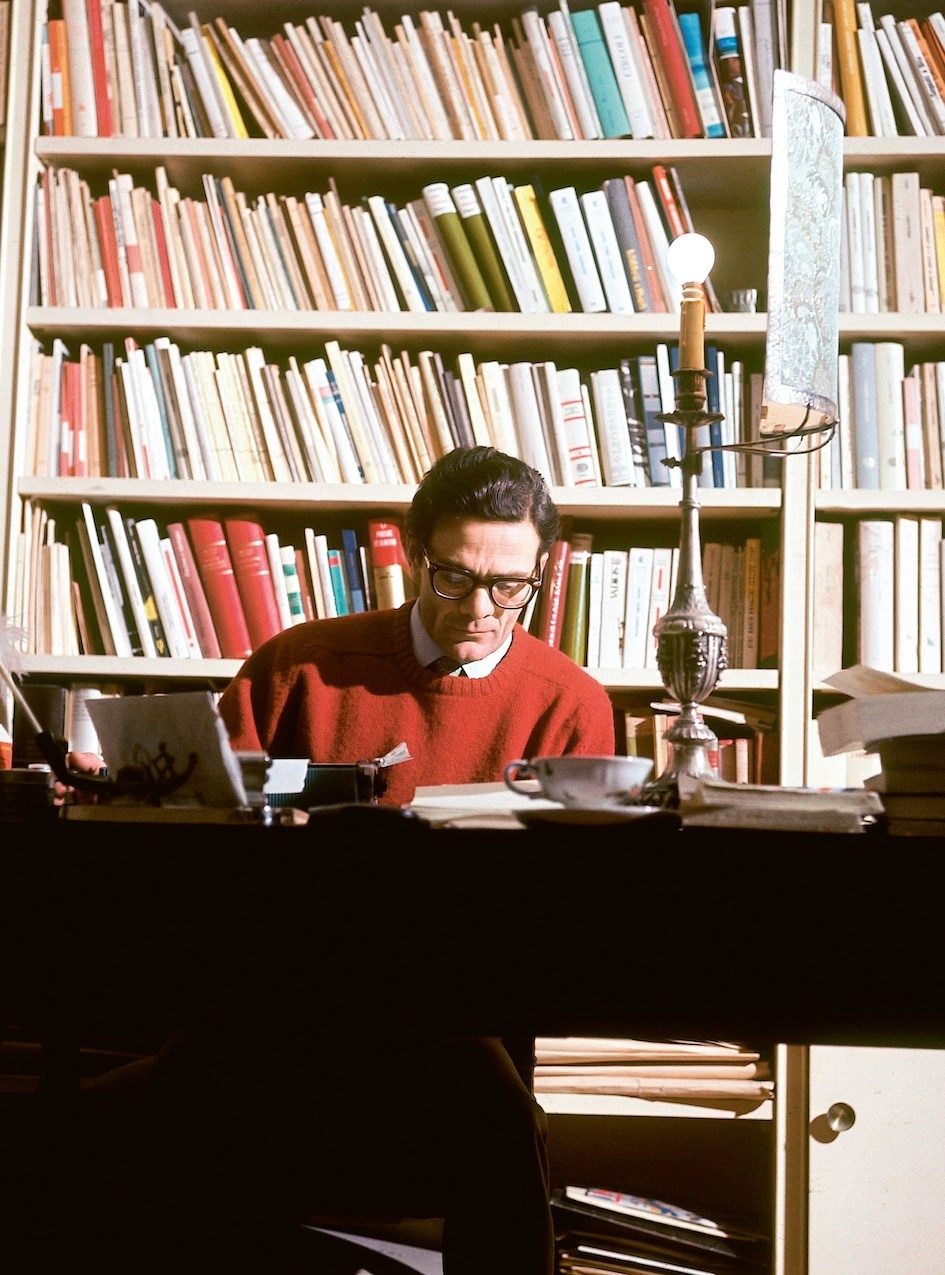

Pasolini was forty when he decided to start making films. Already a renowned poet, novelist, art critic, poet, theorist, painter, journalist, translator, composer, linguist, and political agitator. He wanted to represent the experience of being alive in pure fidelity – he believed cinema was the only way. “A language that expresses reality with reality,” he told Film Comment in 1965. He was driven by “a passion for life: for physical, sexual, objective, existential reality around me... This is my first and only great love and the cinema forced me to turn to it and express only it.”

“As a person, I do pay for what I say... Maybe I’m wrong after all, but I keep on thinking that we are all in danger” – Pier Paolo Pasolini

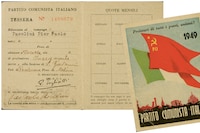

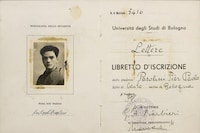

A staunch contrarian, tried thirty-three times for charges like obscenity and insulting the Church, Pasolini was at war with many people, including himself. His life and oeuvre are full of contradictions. His films were an assault on bourgeois morality, but he opposed the legalization of divorce in Italy. He was a non-believer whose reverent film about Christ is beloved by the Vatican. Kicked out of the Communist Party in his twenties for being gay, he continued to promote the group (as they continued to denigrate his work). He remains an icon of transgression, who lived with his mother until the day he died.

His settings pivoted, one film to the next. He abandoned neo-realism for smutty pre-Enlightenment folktales and the Greek mythology of Euripides. He called filmmaking a sacral act while indulging in slapstick sex gags and fart pranks. His adaptation of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1972), the second film in his Trilogy of Life, includes a soused brothel-attendee pissing on revellers below his balcony, castigating them with quotes from Saint Paul and some of his own: “Your face is putrid, your breath is rancid and your embrace is foul!” It ends with a towering Satan explosively shitting out the souls of friars. Against all odds, these films were surprise hits and studios mimicked their tawdry elements to cash in. Pasolini was not happy – his ribaldry was supposed to be anti-bourgeois, if not sublime. He pivoted again: the torture-scene marathon of Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom (1976), an interpretation of the 1785 novel by the Marquis de Sade, was supposed to be the first in a Trilogy of Death. Pasolini was murdered before it was released.

These shifts belie the consistency of his concerns: the purity of the poor and their brutalization by the powerful. This goes for his novels, poems, articles, and rants too. His youth in Rome’s impoverished borgate informed everything that followed. After the war, Italy had gone from a society of farmers to a beacon of industrialized consumerism. Pasolini bemoaned how pollution had killed off the fireflies in the countryside. He not only pitied Italy’s dispossessed subproletariat, he worshiped them. He dreamed of making films for only this class of innocents. But as the 1960s took hold mass pop culture suffused all classes, even his beloved poor. The absurdity, obtuseness, crassness, and cruelty he deployed in his later films were attacks on the zeitgeist.

He plucked his stars from the slums. He referred to these non-actors as “fragments of reality.” He didn’t want them to act. He wanted them to be themselves, to exude their own authentic flair. “Being an author, I could not conceive of writing a book together with someone else,” he explained. “The presence of an actor is like the presence of another author in the film.” To Pasolini, the underclass have none of the camera shy inhibitions of the petit-bourgeois. Their faces evince a purity impossible for an actor to conjure. Mamma Roma’s (1962) Ettore Garofolo was a teenage waiter Pasolini spotted and wrote the film for because his insolent handsomeness and the way he carried bowls of fruit reminded him of Caravaggio’s Bacchus – an artist whose use of light he dissected in his art writing.

He never rehearsed with his actors. He never supplied a script, or even divulged the story. “I simply tell them to say these words in a certain frame of mind and that’s all,” he stated. “And they say them.” He was partial to dubbing, long after it was retrograde. It meant he could shoot without sound and coach his actors along, telling them how to feel, moment by moment. “Like a sculptor who makes a sculpture with little improvised blows of the chisel,” he said. Sometimes he would have the actor say a line and dub in the opposite sentiment to get his desired effect: “I would have him say ‘Good Morning,’ and then I would put in, ‘I hate you.’”

Pasolini is an extreme case of not being able to separate the art from the artist. He cast Ninetto Davoli in most of his films, a ringlet-haired regazzo, who had been Pasolini’s lover from the age of fifteen, when Pasolini was forty-one (Pasolini’s opposition to petit-bourgeois morality extended to the age of consent). When Ninetto eventually married a woman and had a baby, Pasolini was so hurt by his newfound bourgeois leanings that he took revenge on him in his role in Arabian Nights, revealing his penis on camera, then having it severed with a jambiya dagger by bandits. The two nonetheless remained close for Pasolini’s entire life – Ninetto was ultimately the one to identify his body.

“I love life fiercely, desperately” – Pier Paolo Pasolini

Proud to be a non-professional director, untrained and inexperienced, Pasolini invented his own signatures. He shot in truncated slots, rather than long scenes to make it easy on his actors. No dolly shots. Locked-off and static frames, without music or movement – the tight, composed portraits redolent of fourteenth-century mannerist frescoes by Masaccio and Giott

In characteristic self-contradiction, Pasolini’s prejudice against professional actors didn’t stop him from hiring a couple of the greatest stars of the time. He referred to Anna Magnini’s remarkable skill in Mamma Roma as “a problem” during production and saw the film as flawed. Hawks and Sparrows (1966), starring Totò, would be the worst flop of the comic legend’s career. Totò had wanted to make a serious art film. Pasolini insisted he play himself: a clown.

Production limitations didn’t diminish his vision. Pasolini sought epic scale, the lack of budget only enhancing the realism of the vision. The abandoned Southern Italian village of Matera becomes a stand in for Jerusalem. It looks diseased because it was malaria, cholera, and typhoid were rampant. The pimples and wrinkles and toothless smiles are not makeup. Pasolini’s sensibility is well suited for bringing mythology to life. Film may have been the best avenue for delivering his colossal expression of life, but he knew it wasn’t enough to contain it. “When I talk to you about my tendency towards the mythic and the epic – the sacred, if you will – I should say that this tendency can only be completely realized by the act of death, which seems to me the most mythic and epic act there is,” he said.

There are artists who insist on letting their work speak for itself – not Pasolini. He generously elucidated the allegorical meanings he intended. His predilection for the desert as a location signifies timelessness – a symbol for the absolute. Hawks represent the rich and sparrows the poor. In Teorema (1968), a beautiful stranger has sex with an entire family and their housekeeper, one by one, then disappears, leaving them distraught. He represents God. Pasolini was ultimately unmysterious and forthright. What he said has to be believed. “I love life fiercely, desperately,” he told an interviewer in 1970. “I believe that this ferocity, this despair, will bring me to my end. I love the sun, the grass, youth. The love of life has become a vice in me more tenacious than cocaine. I devour my existence with an insatiable appetite. How will all of this end?”

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale now. Order here.