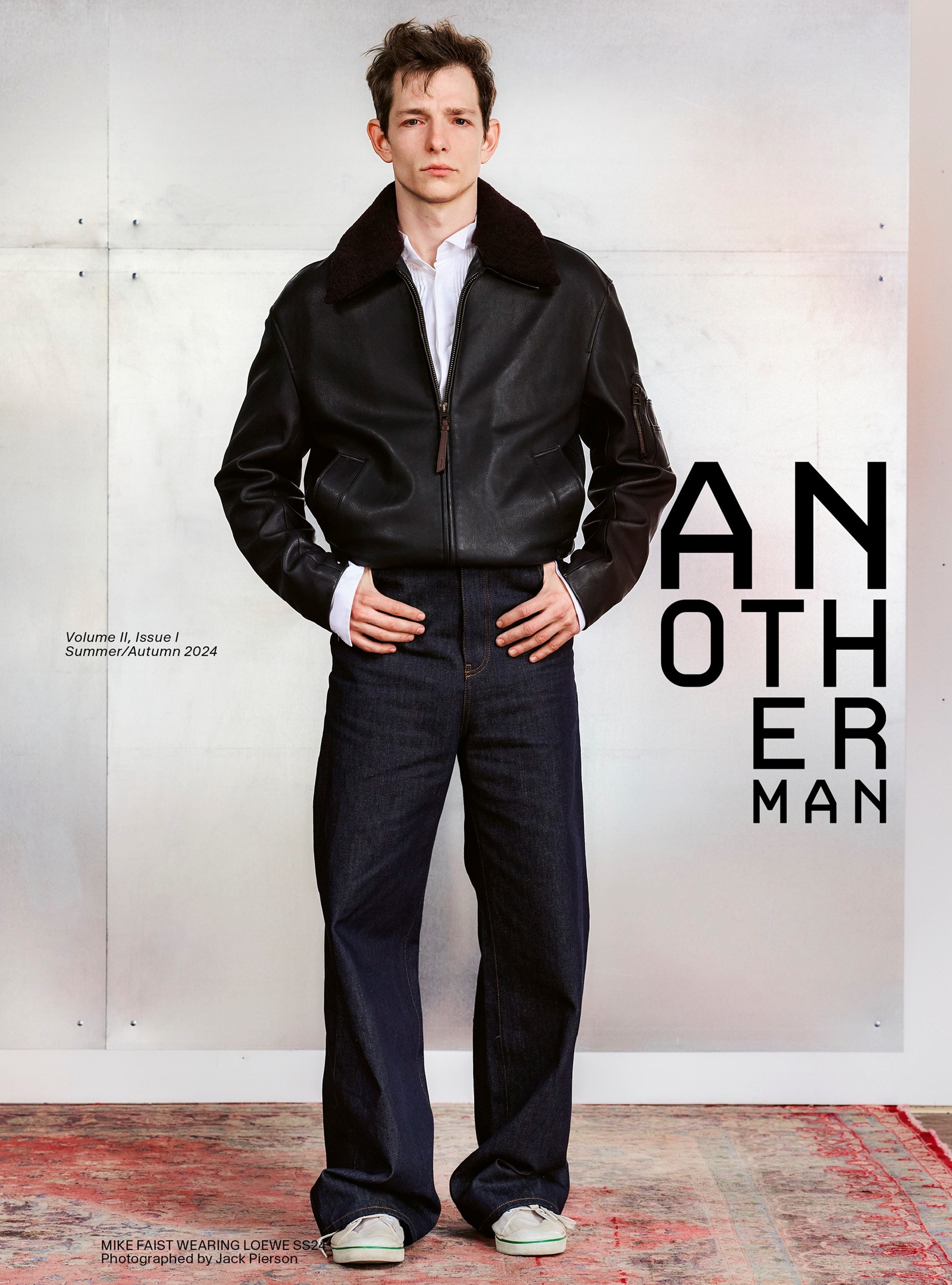

This story is taken from the Summer/Autumn issue of Another Man:

One evening in 2016, the curtains fell on a normal weeknight performance of Dear Evan Hansen at the Music Box Theatre at 239 West 45th Street in Midtown Manhattan. Mike Faist quit the stage with the rest of the cast and was met with a guest, who had come backstage to see him. “I love a ghost story,” said the guest. It was Steven Spielberg.

Spielberg told Mike that he was working on a new film adaptation of West Side Story and that he wanted him to audition for it, breaking from a long tradition of Hollywood directors taking inspiration from Broadway but casting Hollywood actors in the roles. Mike had never thought he’d be in movies but loved the idea of being able to say he’d once auditioned for Spielberg. So, he put a tape together for the role of Tony, but Spielberg ended up giving him the role of Riff, the leader of the Jets – which he was thrilled about, having loved Russ Tamblyn in the original. Plus, “Everyone wants to be Mercutio,” he says.

Mike was lauded for his performance, which earned him a Bafta nomination, though Quentin Tarantino said he should have got an Oscar – something Mike hadn’t heard about before I told him when we met; he expressed a certain bemusement at the news. His portrayal of Riff represented a departure from previous interpretations of the character; instead of a corn-fed all-American type, Mike’s Riff is wild and waifish – he lost weight for the role and pored over Bruce Davidson’s seminal 1998 photography book Brooklyn Gang. “That’s where I found Riff,” he says. “They always cast jocks, muscular guys, obviously alpha guys. But that’s not who these guys were, they’re drunk, broke, heroin addicts, starving … ”

Now, the 32-year-old Ohio native is poised to star in two films: Challengers, the new romantic (read: love triangle) drama from Call Me By Your Name director Luca Guadagnino, starring Zendaya and Josh O’Connor; and The Bikeriders, Jeff Nichols’ new feature inspired by Danny Lyon’s 1967 photography book of the same name, featuring Austin Butler, Jodie Comer and Tom Hardy, which follows the rise of a Midwestern motorcycle club, the Vandals.

The Midwest is where I’m heading to meet Mike – Columbus, Ohio, specifically, which lies an hour and a half up the highway from Cincinnati (presumably a route once traversed by the Vandals), where The Bikeriders was filmed. It’s here, in a suburb to the north-east of the city called Gahanna, that Mike was born and spent his formative years, and it’s here that he returned to in February 2021 when his father got sick, to be closer to his family.

***

Mike pulls up to my hotel in a silver-grey Ram pickup (huge for British standards, modest for American ones). I jump in and he greets me warmly – though not as warmly as his rescue dog, Austin, a pitbull cross, who leaps onto my lap and tries, persistently, to lick my face. Mike wears a scruffy brown shirt and muddy workman boots; a baseball cap crowns his tousled, mouse-brown hair and a beige bandana circles his neck – until he pulls it over his mouth, which happens periodically, when he laughs or, as I later interpret, when he is feeling shy. Confronted with this vision of Americana, it’s hard not to be reminded of Mike’s role as the cowboy Jack Twist (played by Jake Gyllenhaal in the film) in the 2023 West End production of Brokeback Mountain.

I’d been expecting just to go for lunch at a nearby restaurant, but Mike explains that we’re heading out to Woodville, a small town two hours outside of Columbus where his father grew up and his Aunt Christy and Uncle Bernie still live. We drive out of the city and onto the highway, which is roaring with trucks that dwarf Mike’s own. Strip malls, gas stations and chain restaurants flash by and soon give way to farmland – wide-open fields of corn (at this time of year, just a sea of dead, damp stalks) that stretch out like an endless brown carpet laid beneath a grey, wintry sky.

Speaking with a barely detectable Midwestern twang, Mike opens up about the past couple of months: on December 12, his father, Kurt, died of a blood clot, following a three-year battle with pulmonary fibrosis. A month later, his grandfather, known to him as Papa, died too. Death has long weighed heavily on Mike’s mind – in a way that now feels pre-emptive. Despite moving to New York when he was 17 and spending the majority of his twenties there, building his career as a theatre – then film – actor, he moved back to Ohio when his dad fell ill. He sold his flat in Brooklyn and bought a house in Columbus’s German Village, which he has since renovated almost entirely by himself. It now appears that Mike is a quadruple threat: he can sing, dance, act and flip houses. (He can also fly small planes, but that’s possibly less relevant.)

“There’s something very humbling about coming back to Ohio,” he says, “about going off and working with Steven Spielberg, and then coming back here.”

“My friends are super supportive and they’re super proud, but at the end of the day, I’m still just Mike to them, which is great.”

“Have you ever seen Fargo?” he continues, after a brief pause. “Well, in Fargo, they have this amazing Midwestern accent. My family speaks a bit like that.”

After a two-hour drive, we arrive in Woodville, a small, blue-collar town home to just 2,000 people, a lime plant and the oldest Lutheran church in the US, which is where Mike’s father’s funeral took place a few months prior. The church is a stone’s throw from Mike’s aunt and uncle’s house, a typical, clapboard dwelling just off the main street.

“There’s something very humbling about coming back to Ohio,” he says, “about going off and working with Steven Spielberg, and then coming back here” – Mike Faist

When we step through the front door, it appears that we’ve entered an Easter grotto – Mike’s Aunt Cheri takes decorating very seriously, completely transforming her home for every holiday imaginable: not just Easter, Thanksgiving and Christmas, but Halloween, Fourth of July and St Paddy’s Day, too – despite not having any discernible Irish heritage. Easter bunnies, chickens and eggs cover every conceivable space – from the table in the kitchen to the towels in the bathroom.

I’m quite taken aback by Mike’s vulnerability here, bringing me to an intimate Faist family gathering so soon after meeting. He’s opening up in a very real way – inviting me into the home his father grew up in and where he spent all his holidays as a kid. It’s a reflection of ‘Midwestern nice’ (the famously friendly disposition of the people who inhabit the region), but also his desire to be authentic – to show himself, his roots and his real life instead of just a manicured version of it. Instead, I meet Aunt Cheri, Aunt Christy, Uncle Bernie and Cousin John, who have all come over to meet me and, as Mike predicted in the car on the way over, Cheri and Christy have gone all out, putting on a lavish spread of cheese, crackers and ham-and-cheese rolls.

Cheri and Christy talk like Fargo, yes, but also like Jodie Comer in The Bikeriders; in fact, Mike found Jodie’s portrayal almost disconcertingly accurate. “I remember shooting a scene in a kitchen,” he says. “And there’s cigarette stains on the walls and ceiling and she’s just gabbing away in this thick Midwestern accent. I was like, oh my God, you’re my aunt.”

“[Jodie’s] incredible. I have a couple of scouse friends, and when I drove to Liverpool on a road trip [while living in the UK for Brokeback Mountain], I saw a lot of similarities with Ohio. A kind of blue-collar mentality.”

The conversation quickly turns to Mike’s father, Kurt. Cheri and Christy talk fondly of their brother’s sense of humour and practical jokes, including one called ‘the Witch’s Zebra’, which I couldn’t quite follow. “Kurt had the best laugh. He did. No matter what he went through,” says Cheri. “That guy could laugh and make us laugh when we came down to see him after the surgeries. A couple of times we were crying because he would get us laughing so hard about old memories.”

Cousin John, it turns out, was in an alternative rock band called Introspect that once opened for Bon Jovi (the Faist men are musically talented according to Cheri, who admits that the women of the family aren’t gifted in this respect). I ask him what Mike was like as a kid. “He was a quiet young man. And he’s always been very committed to his family. He’s been through a lot of stuff … ” he trails off. “I’m proud of him.”

***

When he was 17 years old, in 2009, Mike graduated from high school early and, like so many before him, left his hometown for New York. His father drove him there and, after a ten-hour journey, dropped him off at a halfway- house dorm room in the middle of Manhattan. “I was terrified,” he remembers. “So was my dad. But I knew I wanted to do this more than anything in the world.” Still, there was a romance to it all: like a scene out of Patti Smith’s Just Kids, he recalls sitting on his fire escape that first night, drinking a coffee, smoking a cigarette and feeling like he’d arrived.

Still, those first few years were tough: he was poor and often hungry. While Jimmy Stewart and Henry Fonda had once lived in his building, and James Dean had lived down the street, his accommodation (then a flat on 64th Street) was pretty basic: his sink was a hole in the floor and his kitchen was a microwave, also on the floor. There were times when he was on food stamps and others when he’d carry around a loaf of bread and a jar of peanut butter because that was the only food he could afford. He worked a variety of jobs: selling tickets for Off-Broadway shows to tourists in Times Square; working as a bar host and runner at Harry’s Burritos; and even, briefly, collecting signatures campaigning for same-sex marriage (he remembers panicking because he only got nine, but when he returned they told him that was amazing and that he’d only been beaten by one person who’d got 13). It was hard, attending theatre school (the American Musical Dramatic Academy) while working hard to make ends meet; many of his contemporaries came from wealthier backgrounds and didn’t need to work while studying. He remembers bumping into the actor (and Dear Evan Hansen co-star) Ben Platt when he was on a job for Postmates (a food delivery service) and feeling so ashamed that he pretended he was doing something else.

After appearing in several Off-Broadway productions, most notably Newsies, he landed a role in Dear Evan Hansen, which made it to Broadway in 2016. Initially, he felt as though he was floundering in the role – “It was a new show,” he remembers, “and it was a character that is more or less a ghost or ethereal, ambiguous creature.” He decided to do some research into suicide survivors online and came across the website LiveThroughThis.org, which tells the stories of people who have survived their attempts to end their own lives. He spoke to Dese’Rae Stage who founded the initiative, and it allowed him a way into the character, lending him understanding and empathy about the experience. “It really grounded me with what I wanted to do with the role. Since then, research has been my way to feel more secure, to feel like I am prepared. Even if you have to throw it all away in the end.”

Then of course came West Side Story, which remains the project he is most proud of and a convergence of everything he wanted to achieve. Working with Steven Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner, he says he found pieces of himself he never knew existed and let go of his inhibition. “It felt transcendental,” he says. “It felt like: I’m not me right now, I’m being used to tell the story in the best way possible. I don’t know how to explain it, it was like I had no control over the situation. It was like being used as a vessel, and that was the best feeling ever.”

***

After wrapping up lunch, we head back to Columbus, driving back through the Ohioan countryside, with Sufjan Stevens playing on the speakers. This feels appropriate for several reasons: not only is Stevens a fellow Midwesterner (the singer-songwriter hails from Detroit, Michigan), but he shares a similar sensibility to Mike: he too is thoughtful, poetic, and committed to his art. As with Stevens, fame and celebrity feel like an accidental or even unfortunate side-effect of doing what Mike loves. “I don’t want to do this as a job,” Mike says at one point, staring ahead at the road before him. “For me, it’s deeper than that.”

I thought this might be the end of our interview, but we arrive back at Mike’s house in the German Village and he beckons me in, introducing me to his roommate Dan, who has known Mike since he was 16 – the pair met acting in plays at high school. What was Mike like back then? “A loose cannon,” Dan says with a wry smile. “Eccentric,” Mike corrects. “Floaty and an idiot.” He was going through a rebellious stage in this period of his life, and, while this didn’t mean anything too nefarious (he was mainly just smoking and selling a bit of pot), he wasn’t heading down a good path and was bored stiff. It was theatre that saved him: he was keen to take part in the various productions his high school theatre club was putting on, but his teacher, Miss Macioce, disallowed him because of his behaviour, which is when he decided to make a change.

Mike shows me around the house he did up with some help from his dad before he died. It’s handsomely but humbly decorated, with a fair amount of older or thrifted furniture and a picture of his dog Austin (drawn by a young neighbour from Gahanna) hanging in the downstairs loo. His bedroom is painted dark green and books line the walls; it looks like a normal thirtysomething’s bedroom, except for the flash of gold on the bookshelf – the Grammy he and his castmates won for Dear Evan Hansen. (They were also nominated for a Tony for this.)

We head out to take Austin for a walk through German Village, the oldest and most affluent part of Columbus populated with lawyers and doctors who work at the local children’s hospital, one of the largest in the US. Real gas lamps flicker in the porches of smart, red-brick Victorian houses built by German settlers who arrived here in the early-to-mid-19th century; front gardens are lined with coiffed box hedges, while Ukrainian flags fly alongside the regular Star-Spangled Banner, indicating the liberal values and Democratic leanings of the neighbourhood. Two kids come up to say hi to Austin and Mike chats amiably with them, producing some dog treats for them to feed him (Austin appears to be more famous here than Mike).

An hour or so later, we’re still hanging out and sitting at the bar of a nearby restaurant called Cobra, which was set up by Alex, another high-school friend of Mike’s. It’s been an unmitigated success – the place is packed. We’re having a fairly furious debate over which superpower would be preferable: the ability to fly or be invisible. Mike wants to be invisible which I think is ridiculous, because what – besides things that are a) creepy or b) illegal – is being invisible good for? Doing random acts of kindness, like watering an old lady’s garden, says Mike. I laugh. Dan and two more high-school friends, Garet and Kaine, join us and quickly the debate resurfaces. Obviously, everyone agrees with me, but Mike isn’t backing down.

“I don’t want to do this as a job ... For me, it’s deeper than that” – Mike Faist

I suspect that the real reason is Mike’s discomfort with the public position his job is putting him in. He’s dreading the Challengers press tour and admits he was even dreading this interview a bit. It’s part of the reason he enjoys Ohio; no one knows who he is or treats him any differently. The gift of invisibility – or anonymity – is attractive to him.

On set for Challengers, Mike says he felt a natural synergy with O’Connor who “just wants to make pottery and be in his garden” in the Cotswolds. “I think he’s a bit more accepting of it all than me. Because he’s always had to do a lot more of it [press tours, et cetera], so I think he’s at least mentally prepared. And I’m like, coming around slowly. But luckily, Z [Zendaya] is a pro.”

“But she grew up with it, you know, kid actor and Disney Channel … It’s a different world … I think it really got crazy for her while we were shooting actually, when she fully acknowledged the scope of her fame. Because we were in Boston and she had an apartment and she just couldn’t walk outside. I would take Austin to the park, have a cup of coffee and walk around, and she just couldn’t do that.”

Mike doesn’t have this problem yet. Here in Ohio, his friends don’t treat him differently. To them, he’s the same guy they befriended at theatre club all those years ago. They’ve all rallied around him in the wake of his father and grandfather’s deaths and their support, as he says on multiple occasions, means a great deal to him.

These friends soon decide that I need to experience a proper American dive bar, which is where we head next: a crowded, noisy and sweaty place crammed with locals. There is sport on the TV and darts are being played in the corner. I’m soon plied with Busch – a classic Ohioan beer – as a couple more of Mike’s high-school friends join us: Julia and Garet’s wife Aileen. The gift of flight or invisibility debate soon rears its head again, but Mike is still unable to find a majority.

***

It’s the next day and Mike and I are discussing Challengers and the preparation he had to undergo to play a professional tennis player. He’d suggested meeting again and had picked me up from my hotel early in the morning to drive me to a Waffle House, where we’re now eating a classic syrup-laden American breakfast.

Breakfast, in fact, was a key part of his preparation for the film: he had to eat eight scrambled eggs every morning to help build up his physique, and work out for four hours a day for 12 weeks – he put on 20lbs of muscle.

“I enjoyed working out, but I think it made me feel like I lost some brain cells,” he says, laughing. “I enjoyed the challenge, I enjoyed the ritual of it, but I don’t know if I need to be eating a cake every morning. I was eating like every two hours.”

Tennis, of course, formed a big part of his preparation too; he was trained by Brad Gilbert, a former player who has won 20 pro singles tournaments and coached Andre Agassi and Andy Murray, among others. “Brad was really insistent that my character, Art, played with a one-handed backhand and his reasoning was that there was this big rivalry between Andre and Pete Sampras. Andre was more like the wild child, like Josh [O’Connor]’s character, and Pete was the more ritualistic, professional, disciplined one. Brad got really interested in that dynamic, so he was like, ‘You’re gonna play with the one-handed backhand.’”

The build-up for the film had challenges that went beyond the physical, too. Mike admits he had some hang-ups about taking on the role – insecurities that sometimes flare up about his being a small-town boy from Ohio working alongside major-league actors and directors. But as his performance in the film shows, he not only holds his own alongside Zendaya and Josh O’Connor (no mean feat) – he shines. His role is the more challenging; while Josh’s character, Patrick, is the slightly more cocksure bad boy, Art is a more internal, introverted character which Mike plays deftly – it’s more than skin-deep; he inhabits the role totally.

One line from Challengers that stuck with me occurs when Art is contemplating giving up his career in tennis. “I’m tired,” he sighs, in a way that expresses a weariness that is deeper than physical exhaustion. It’s the weariness of having pursued your dreams for ten years and being worn down to a point of real, inescapable fatigue. I ask him if he relates to this at all.

“What drove me to understand this character – why I liked and was interested in the character – was this idea. In Andre Agassi’s memoir, he talks about why he hates tennis throughout the entire book. And I understand,” he says, as we continue to eat breakfast. “The reason I moved to New York was to become an actor – like, I had no choice. And yeah, when you’re in your twenties, you’re just trying to get your foot in the door and make it happen by any means necessary; you’re gonna show up and you’re gonna hustle.”

“I enjoyed playing Art because I have a strange relationship to acting: I really love it, but at the same time I get so exhausted by it. And I fall in and out of love with it on a pretty regular basis. It’s just the truth of the matter. So I think I really understood Andre, and Art, when they talk about this idea of falling out of love with your craft.”

He felt another synergy with O’Connor in this respect: “Josh is always torn too. Honestly, he’s more Art than me … He’s like, ‘I’m tired.’”

It was on the set of Challengers where Mike first met Jonathan Anderson, who worked as the costume designer on the film. The pair quickly struck up a friendship – Mike says he appreciated Anderson’s sarcastic sense of humour. The designer later asked Mike to appear in a Loewe campaign (for the SS24 pre-collection) and while Mike was initially reticent, it was soon apparent that Jonathan wasn’t going to take no for an answer. On set, Mike had his initiation into the world of fashion and particularly took to photographer Juergen Teller, who shot the campaign and entertained Mike with the story behind his famous photo of OJ Simpson. “I love Jonathan no matter what,” he says. “He’s a great guy and a great friend.”

***

Later, we drive over to Gahanna, where Mike grew up. The houses are bigger and more spread out here, and it’s a lot leafier; there are bigger yards, lots of trees, with the odd lake or oversized pond. He drives me past his high school, which is currently getting an extension and vast new football stadium (a lot of pressure on the football team, the Lions, he says), and past his mum’s office, out of which she’s practised law for the past 40 years, only retiring last year. We keep driving on, past his friends’ houses – where Kaine, a friend we’d met last night, used to live; where a former girlfriend used to live; where other people he’d spent his teens mucking about with used to live. Many of them have stuck around; others flew off like Mike did, only to circle back home in their late twenties and early thirties.

Finally, we arrive at a classic American suburban home, with an open garage and stuff teeming out of it. We enter the house through a door at the back of the garage, Austin in tow, and hear the yapping of dogs. Two King Charles Spaniel-Shih-Tzus race out to meet us, a flurry of white fur and shining brown eyes the size of saucers. Charlie and Huck (named after Huckleberry Finn, of course) are followed by Mike’s mum, Julie, who sits down with us in the living room, where family photos sit framed on shelves and two sofas face a large TV (Julie loves home makeover shows).

“At two years old,” she says, “Mike became obsessed with dancing.” His grandmother, who had been living with them at the time and was suffering from dementia, loved old movies and would watch them on repeat. Mike, therefore, spent his first few years on Earth soaking up Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire like a sponge. “I’m going to be Gene Kelly one day,” he told his mum, before asking if he could go to dance class. Julie did her best, but couldn’t find a dance class that accepted infants, so Mike had to wait until he was five before finally enrolling in one. “He was born an adult,” says Julie. “At six, he told me he wanted to start saving for college. At six!” He asked her to write to the Barney show and see if he could go on it, but that didn’t work out, and Mike got his first taste of the cruel world of showbiz. He continued guzzling down Gene Kelly movies – On the Town, An American in Paris and, most importantly, Singin’ in the Rain, which he still ranks as one of his favourite films of all time.

According to Julie, Mike thought Gene was “the perfect man” – “he could do everything and would always get the girl. That was important: he always got the girl.” He started to wear suits to pre-school – a school photo on the shelf shows Mike in a pinstriped suit, smiling ear to ear – and even, on occasion, took to wearing a top hat. Julie encouraged Mike to try his hand at everything – from baseball to basketball and tennis, which has now – thanks to The Challengers – come in handy. He even had a brief but successful stint as the school mascot, donning an enormous lion costume to football games. This was largely an excuse to hang out with the cheerleaders, but when I ask if he had any luck in that department, he laughs. “No, I was definitely not cool enough for that. I think I sold them some pot though.”

“I enjoyed playing Art because I have a strange relationship to acting: I really love it, but at the same time I get so exhausted by it. And I fall in and out of love with it on a pretty regular basis” – Mike Faist

It was at dance class where he really shone; Julie said he was always leading the other guys – at nine, he was helping dancers eight years his senior learn the choreography. One time, when they went to a Broadway show, Mike came home and wrote down the entire choreography – literally typed it up – and then taught it to his classmates, which they then performed (or rather, plagiarised, says Julie).

He didn’t do many school plays but there was an alternative theatre arts school in Columbus, and he decided to go there. His first production was an American play called Life With Father, in which he played one of the sons. And then he took part in a production of Grease – playing Danny Zuko, naturally.

Mike, Austin and I go out for a walk, through the wide streets and large front yards, down into the woods that back onto the suburbs. Here, Mike, spent his youth, messing around, collecting frogspawn and later smoking et cetera. The weather is unseasonably warm as we walk down by the creek, through the woods and onto a football field, where kids are warming up for sports to the sound of Soulja Boy. It’s a supremely American scene.

Mike suggests that we go to the cemetery where his grandfather has just been laid to rest. No one from the family has been there yet, and again I’m taken aback. His sister, Krista, calls on the way down, and Mike explains where we’re going. We’re not entirely sure where – in the sea of stone plaques, metal vases and artificial flowers that stretches out before us – his Papa has been laid to rest, and we search for half an hour in the fiery glow of the Ohioan sunset before calling it quits. We head to a brewery a half-hour drive away to catch the last embers of sun sinking down over Columbus and discuss The Bikeriders.

In preparation for the film, Mike spent two days in Maine with Danny Lyon, who he plays and who gave him some photography lessons. He takes out his Fuji camera and flicks through the photographs that he took on set, some of which represent restagings of Lyon’s original photographs, which will be compiled into a photo book. “It’s a small part but I just wanted to watch these great actors – Austin, Jodie, Tom. I wanted to be a fly on the wall and just be there. I was learning photography at the time and it was a great opportunity to get paid to photograph some of your idols. And it was in Cincinnati, so close to dad, and around the holidays.”

***

Once we’re back on the road, we decide to stop off at Massey’s – a local roadside pizza joint about 15 minutes away. His father loved this place and Mike says he would have found it hilarious that we’d come here. The air is thick with the smell of oil and cheese, and the interiors look like they haven’t been touched since the 70s: neon lights in the window; a swirly, navy-blue carpet; sticky, plastic tables; no music, just the sound of chatter from the few other diners. Julie joins us and we discuss family; how her grandparents had arrived in America, how her parents came up from the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression, and lived that Grapes of Wrath life. “That’s the Midwest,” says Mike. “Everyone has the mentality of work, work your ass off.”

“That’s the unfortunate thing about America. That’s something that physically hurts me,” he continues, his voice cracking and his eyes suddenly smarting with tears. “Because I’ve been so fortunate in my life to have crazy adventures and pursue my dreams. And my mom and my dad … They just worked so hard to make sure I was able to do what I do. And I don’t know, the cost of that, on their health and whatnot … ”

To date, Mike has made interesting choices in projects he’s decided to take on, which reflect his instincts and interests as an artist. And while he loves acting, he doesn’t love everything that comes with it. In many ways, I wouldn’t be surprised if Mike did a few more roles, had a five-year break – during which he flips houses for a living and enjoys a more regular existence in Ohio – and then comes back and does another role that lands him an Oscar. “I had this conversation a lot with [The Bikeriders director] Jeff Nichols, saying that I only really want to do pieces that come from a place of love,” he’d said earlier on in the day. “Like, it’s coming from me. Like not necessarily for love, but from love. It may not be good [laughs] but it’s coming from that place of ‘I’m free, I’m liberated, I’m the most authentic I can be.’”

After dinner, Mike makes me drive his truck part of the way home (despite my lack of pretty much any driving experience or, more crucially, a driver’s licence – we both fear for our lives), concluding not just a whirlwind journey through Ohio, but through Mike’s life. As we part ways, I wonder where his journey will take him next, and how these two major films will affect its course.

Hair: Tsuki at Streeters. Make-up: Kiki Gifford at Streeters. Talent: Mike Faist. Lighting: Eduardo Silva. Photographic assistant: Nathaniel Jerome. Styling assistants: Bella Kavanagh, Alexander Bainbridge, Umi Jiang and Alexa Levine. Production: Second Name

This story features in the Summer/Autumn issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from April 25, 2024. Pre-order here.