Presented via a “show-in-a-box”, Jonathan Anderson’s Autumn/Winter 2021, women’s pre- and men’s Eye/Loewe/Nature collections paid tribute to seminal American artist, poet and writer Joe Brainard

‘Collage’ is an apt way to describe Jonathan Anderson’s tenure at Loewe thus far. For his conception of the Spanish house has always encompassed much more than just clothing, with exhibitions, artistic collaborations and an ongoing craft prize all part of the rich amalgam of influences which form the designer’s unique worldview.

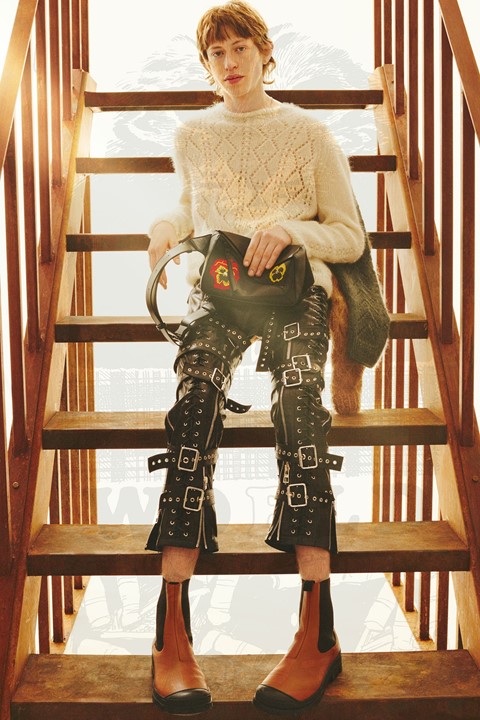

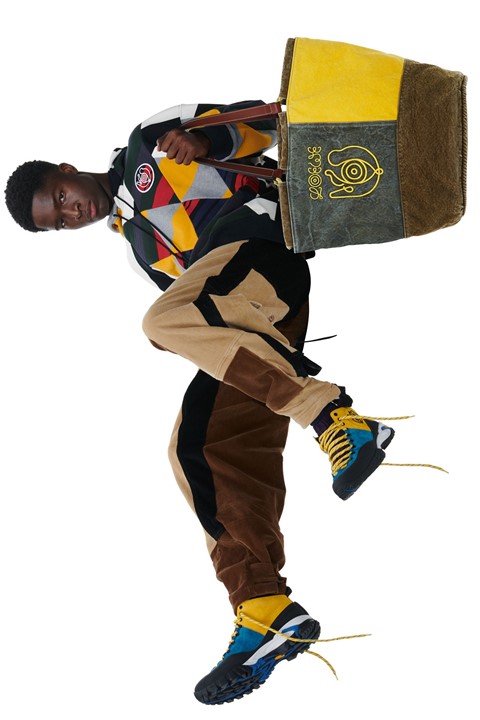

This past weekend, Anderson used the term to describe his most recent collections – Autumn/Winter 2021 menswear and a women’s pre-collection, as well as sustainable men’s offshoot Eye/LOEWE/Nature – presented via his latest “show-in-a-box”, a concept devised at the very beginning of the pandemic as a Covid-safe way of expressing his vision in lieu of a catwalk show. “A sense of thoughtful accumulation,” the accompanying notes described. “Each garment is a collage, therefore the look becomes a collage of collages.”

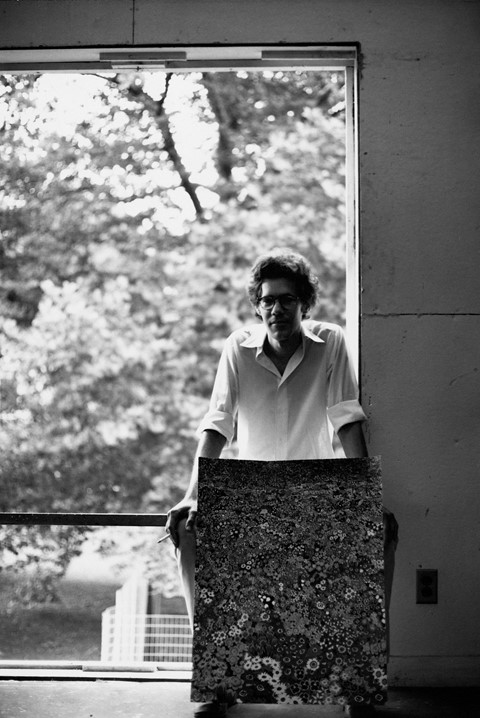

Contextualised in what Anderson this season called ‘A Show in a Book’, those looks were set alongside a singular hard-bound monograph dedicated to the work of queer American artist Joe Brainard (1942-1994). “A catalogue for an exhibition which is yet to take place”, as Anderson describes, it contains Brainard’s rarely seen collages, illustrations, collected ephemera and comics, as well as a preface by poet Ron Padgett and an essay by French critic Éric Troncy. It’s a rich, comprehensive tribute to an artist who, despite being a part of the New York School and the beginnings of the Pop Art movement, remains relatively overlooked, his career cut short by Aids-related pneumonia in 1994 (sales from the book’s release in June will help support Visual Aids, an organisation which uses art to fight the disease by “provoking dialogue, supporting HIV+ artists, and preserving a legacy”).

Anderson was originally drawn to Brainard for the sheer breadth of his output – his will to operate “outside of rulebooks and categories” – which also includes work as poet and writer, a contemporary and collaborator of Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery and Amiri Baraka (an experimental memoir, I Remember, published in 1970 also remains in print – Anderson says he loves “the humbleness of his writing”). But it was Brainard’s collages – or ‘assemblages’, as they are often categorised – which felt particularly prescient to Anderson, who was fascinated by his “ability to create things out of the everyday”, an accumulation of a life lived on New York’s fast-changing Lower East Side in the 60s and 70s.

“Within Brainard’s work there’s this idea of finding something in the absurd, the outrageous, in the found object,” Anderson says over Zoom. “It’s this idea of re-presenting things as an idea. Over the year when I was researching this collection, I liked his mentality of taking something like the pansy and by using it as a painting, or a repetition, or a symbol – and everything the pansy means in terms of gender, of queer culture – he can make us question information. I’m all about this over both brands at the moment: what you see, is it what you are getting?”

Brainard’s pansy – most famously immortalised in his 1967 mixed-media collage, Untitled (Pansies) – is a recurring motif throughout the collection, whether as a miniature charm on a necklace, a patch on a pinstripe blazer, or blown-up on enveloping jacquard-knit cardigans and trousers. For Anderson, the “childlike” immediacy of the image felt apt to the moment, one in which he is finding himself working more and more with intuition. “I haven’t got time in this moment to be over-thinking; the book has to happen, the collection has to happen, there’s this immediacy to getting the idea out,” he says. “The look itself is very immediate, it’s not over-complicated. It’s an urge to put together something that feels right to me.”

It comes back to Anderson’s desire to push forward, to begin to envisage a world beyond the confines of the current moment. “I‘m really about projecting optimism here,” he says. “I love fashion. Fashion is about projecting into the future. If I design something that is for the future, hopefully we will get there. I don’t know if we will, but we need to have optimism, have imagination. If you make something, and you believe it’s going to happen, then it will happen.”