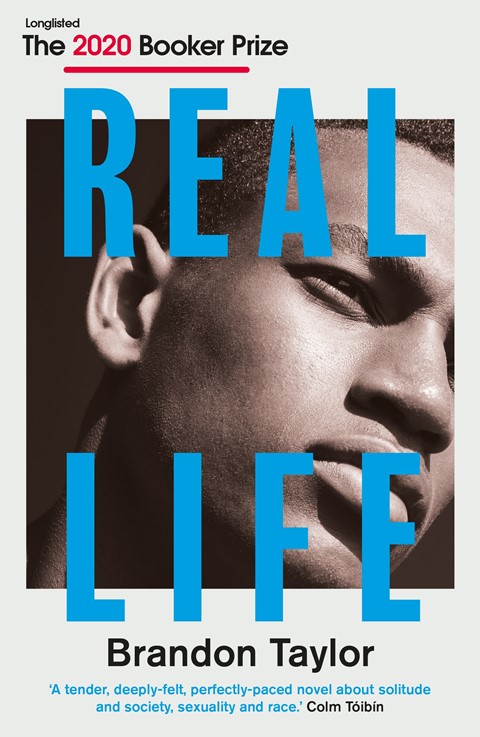

“I’m just trying to be honest because if you’re not you’re just protecting whiteness,” says Brandon Taylor of his Booker Prize-nominated novel Real Life, which depicts the life of a Black queer man studying at a university in the American Midwest

Real Life, by Alabama-born author Brandon Taylor, is about a Black queer man from Alabama pursuing a PhD in biochemistry at a university in the American Midwest. The debut novel – which has been longlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize – was warmly described by judges as “a deeply painful, nuanced account of microaggressions, abuse, racism, homophobia, trauma, grief and alienation”.

Of course, Taylor is delighted to be in the awards conversation but something doesn’t sit right about this line of praise. It’s not that the book isn’t those things. It is. But it’s also so much more and importantly, a lot less.

“When I say stuff like ‘I’m not writing for the white gaze,’ it’s not me trying to be provocative or messy, it’s what I really think and it comes from a really deep place. I’m just trying to be honest because if you’re not you’re just protecting whiteness,” says Taylor.

Despite touching on a number of serious issues, when we talk Taylor is always willing to laugh in the lighter moments. He never browbeats and, like all genuinely smart people, he makes you feel smart when you talk to him even if you’re struggling to keep up as discussion flits between his existentialist forebears Camus and Sartre and his famous fans like Jeremy O Harris (the Black queer playwright behind Daddy and Slave Play) and Michael Arceneaux (writer of I Can’t Date Jesus, a New York Times bestselling essay collection).

Given the way it has been described, you’d be forgiven for thinking Real Life is a polemic in novel’s clothing, an unremitting look at the Black man’s burden in a world where white is king. But if the novel makes any points, it does so quietly. “It wasn’t my goal to deconstruct whiteness,” says Taylor. “I just wanted to write a novel in singular pursuit of truth and honesty about what it’s like to exist [as a POC] on campus.”

Maybe it’s just our current moment but this was the part of the book that resonated most deeply with me. Reading Real Life during the summer when Rhodes finally fell served as a reminder of how universities so often fail to provide a positive environment for people of colour. “When you first arrive, college feels like an opportunity to escape the shitty parts of your past. So I wanted to write about what it’s like to come to view it as an extension of all the things that are seeking to destroy you,” says Taylor.

To his credit, Taylor’s novel unflinchingly captures the uncomfortable reality of life as a student of colour. But when his novel was predictably described as “raw” and “visceral”, Taylor knew he had to take a stand. “Some of the early reviews were really concerning to me because they were talking about the book in ways that I wasn’t comfortable with,” says Taylor. “I know what that cliché stands in for. I know why they say that: it’s just a response to the physical discomfort of moving through the world as a person who’s been marked by these various oppressive hierarchies.”

Taylor feels that in describing the book as “raw” or “visceral”, critics are failing to meet the book on its own terms. Instead, they are grasping for clichés because they lack the intellectual architecture to process experiences that fall outside their own narrowly white expectations. But Taylor’s opposition to this brand of criticism goes beyond a race thing. It stems from his natural desire to be acknowledged for his skills as a writer, and not just his bravery as a Black queer man.

“When I say stuff like ‘I’m not writing for the white gaze,’ it’s not me trying to be provocative or messy, it’s what I really think and it comes from a really deep place. I’m just trying to be honest because if you’re not you’re just protecting whiteness” – Brandon Taylor

“When you call something raw I feel like you’re characterising the texture of the prose and, if anything, my prose is incredibly cold and aloof,” says Taylor. “It’s very stripped back and so I feel like calling me raw is like calling André Aciman (author of Call Me by Your Name) or Joan Didion raw. The texture of their prose is so clean that no one thinks to describe it in that way. But if I write about the same difficult stuff I get called raw because I’m Black. I just don’t get it, to me I had written a contemporary intellectual novel, just with gay Black people in it.”

Unlike previous generations of Black writers, Taylor has social media. This grants him a platform from which to steer the conversation around his work. “Because the media has this blind spot around the way young authors use Twitter I get to do all these things like tweet about how annoying it is when a Black writer’s work is called raw and visceral. Sure, some of my work can be thorny about questions of race and class but with Real Life, I was just like ‘it’s fiction, no one can tell me what to do!’”

The importance of this last point cannot be overstated, especially now that race is being dissected more keenly and also more routinely than ever. Real Life came out back in March but this summer it took on a life of its own when the race conversation the book had engendered was subsumed by the anti-racism protests that raged following the murder of George Floyd. “As an American, I’m very wary of all this. It’s like you guys have made these promises before but it’s bananas to me that people are getting fired for racism in America!”

Seeing Real Life become a part of that conversation, has been a gratifying, if surreal experience for Taylor. “Whenever these conversations flare in the States that’s when white people suddenly think ‘I’m gonna go buy books by Black people’ and at the best of times they’re coming to our work with an anthropological curiosity.” Still, Taylor feels lucky to have reached a wide and diverse audience even if it means having to have the occasional frustrating conversation with a tone-deaf critic.

Ultimately, he is thankful for the book’s modest origins as he found the paucity of expectation to be liberating. “The only thing you can do when you sit down to write a book is try to tell the truth,” says Taylor. “I just want to be responsible for the characters I create. Your work should never be constructed under the duress of someone else’s value system.”

I ask if the success of Real Life necessarily means he’ll never have that freedom again – after all, if he is shortlisted for this year’s Booker Prize expect to see his work be described as raw and visceral another thousand times. But Taylor is unperturbed, having already long moved on to the next project.

“I’m trying to focus on the task at hand and not let the world in but there’s a weird pressure now, knowing that people are going to see what I do next. I’m just grateful for Real Life because it’s the book that I wrote to change my life and then my life changed. How can I look at it any other way than as a great gift!?”

Real Life by Brandon Taylor is out now, published by Daunt Books