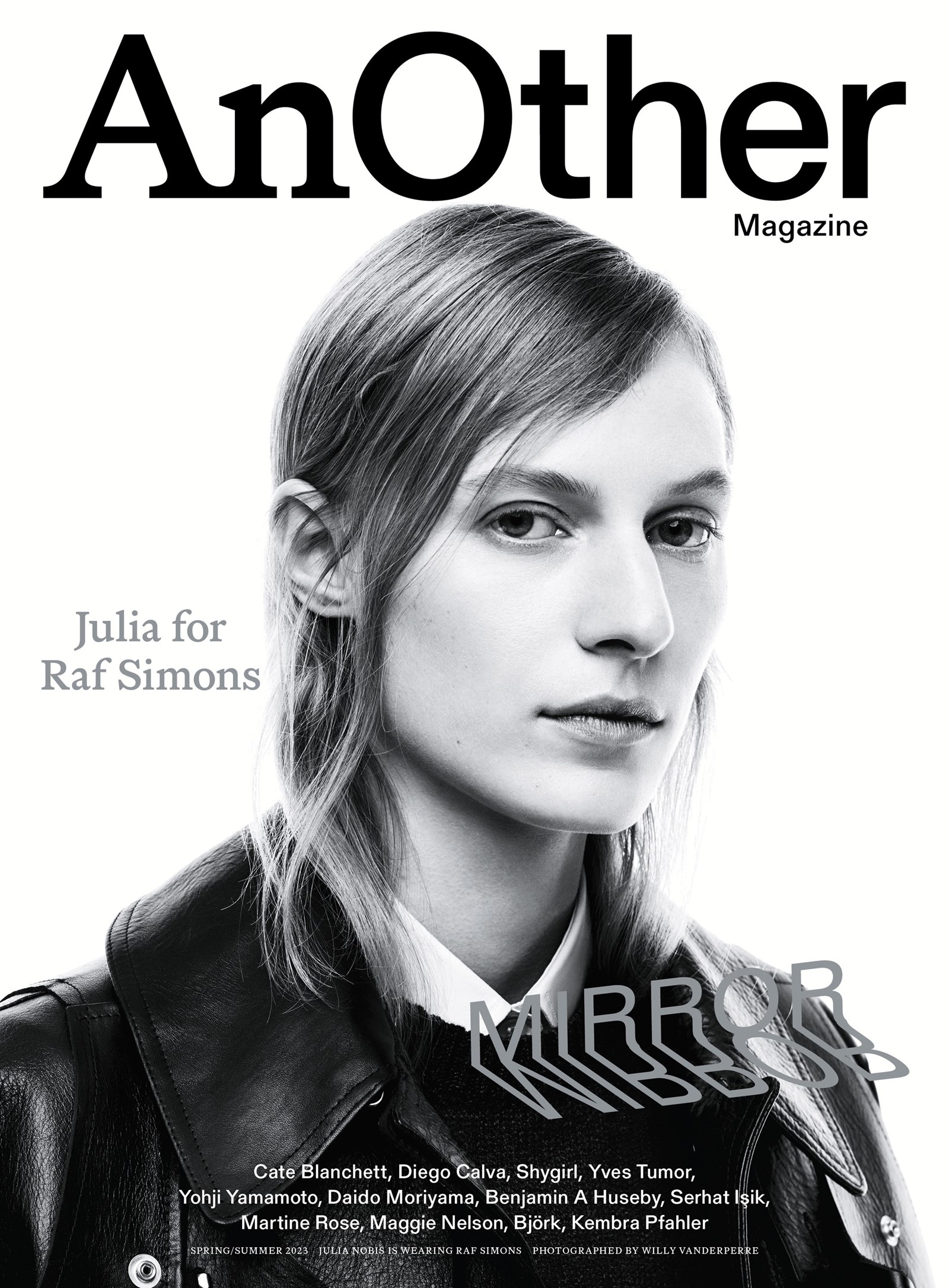

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Susannah Frankel: I just changed – I swear this is true – out of the exact same hoodie you’re wearing.

Raf Simons: You’re wearing Ralph Lauren when you are having a Zoom with me?!

SF: Mine was a present to my son when he was 12 that I stole back. But I thought, “I can’t wear that to talk to Raf.”

RS: I do have something much cooler under the hoodie – a Blue Velvet T-shirt. We were in Tokyo over New Year – it was the first time in my life I could really travel in that way, because before with the brand I could not even go away from Antwerp – and we shopped.

SF: Which brings us neatly to ...

RS: I was just going to say.

SF: Can we talk about your last show? I am quite interested in talking about it in comparison to your first show. The feelings and atmosphere around the last one, and then the first.

RS: Were you at the first show? Because that was quite something, that first show. But I did four collections before even showing.

SF: That, I knew.

RS: And I never really thought about showing, actually, when I started. Everything was so ... So different, let’s say. I thought, “If I can try to make clothes and somebody will like it, I will be happy.”

The first collection was not even in Paris, it was in Milan, because of Linda Loppa [head of the fashion department at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp for more than 25 years]. She sent me to an agent, Daniele Ghiselli, who was at the time the European distributor for Helmut Lang. I drove there, in my own car, with a small collection of hardly 40 pieces. And then it was hanging in a room next to Helmut Lang. So I was like, “Oh wow, that’s incredible.”

When I was still in industrial design school in Ghent I did an internship at Walter Van Beirendonck, but I also helped him out for several seasons afterwards, to do presentations. He brought me to Paris and to my first shows – two shows. One was Martin’s, the show everybody knows [Martin Margiela Spring/Summer 1990]. And another show I saw that same season was the Gaultier show, with the nuns that came up out of the ground and Neneh Cherry. There was such a hard contrast – that show was a big spectacle in an arena, with a round catwalk. But it was of course the Martin show that completely changed my perception of how fashion could be. And I was nagging Linda Loppa, because all that made me think, “Oh, maybe I should study fashion.”

I tried to enter the Antwerp academy, but Linda would not allow me. Yet she was very interested in furniture – so she and her husband would help me out. She was thinking, “Oh, maybe we should find some galleries who can work with your furniture.” For at least a year and a half, two years, I would see them every day. I would also see a few other people that you know very well. Olivier Rizzo was one of them. Willy Vanderperre. Peter Philips. It was a bunch of people from the same generation, and they all came from the Antwerp academy.

“And I never really thought about showing, actually, when I started. Everything was so ... So different, let’s say. I thought, ‘If I can try to make clothes and somebody will like it, I will be happy’” – Raf Simons

And then I thought, “You know what? I want to start designing clothes.” I actually started with two girls – I thought, “I can’t do it alone.” One girl was a right hand to Dries Van Noten and the other was a pattern maker. We started together, lots of talking, but they were just like, “Oh my God, it’s too scary. I can’t do this.”

This is the story that most people don’t know – it’s the real story, actually. I said, “I’m going to do it anyway.” Linda Loppa’s father was a tailor – “He can help you out,” she said. Because I didn’t know how to make a pattern or anything. He then connected me to a very young graduate tailor. I found some Belgian producers and made a small collection. Because Linda kept saying, “If you think you can do it, show me that you can do it.” So I just made the stuff.

And because I went with Walter to Paris I saw how designers presented themselves – they would always build a world. That’s also what I did. So I made a video. It’s the first video [Autumn/Winter 1995], of two boys walking. The guy that is in the video with the long hair, he was actually a young video maker, who I knew a little bit from going out, who I thought was also great-looking in the clothes. Extremely skinny, obviously. He filmed it. And another one – extremely skinny, obviously, but also cool. Not models. All with Sonic Youth music. But when I went with all that to Milan, it didn’t really seem so interesting for Ghiselli. He said, “I just want the clothes.” I was a bit disappointed I couldn’t present it the way I had envisioned it. It was more about that for me, rather than about clothes.

I drove back from Milan and Ghiselli called me a day or two later and said, “I have orders. Can I fax them to you?” I didn’t have a fax machine, so I had to go to my parents and borrow money – because all my money had gone on the clothes – to buy a fax machine. Orders rolled in, seven orders from Japan. Total panic attack – oh my God. I called Linda Loppa and she said, “Yeah, you have to sort it out now.”

From then on she always said, “I knew you had it in you. That’s why I forbid you to go to the school. You would have said, ‘Fashion, it’s not for me.’”

SF: That’s an example of a great teacher, isn’t it?

RS: Yeah, well it didn’t feel like that at the time. I was so mad at her.

That first video was two boys walking in and out. The second video [Spring/ Summer 1996] was shown in a small gallery with no invitation. That was the video that Olivier Rizzo and I did – where Olivier was holding a lamp in my house and I was filming with this 8mm camera. Black and white, just some kids hanging around and dancing. A couple of boys and Veronique Branquinho.

Alexander Fury: It’s the party one, isn’t it?

RS: They’re just hanging out in my small apartment, actually. The third video [Autumn/Winter 1996] is very David Sylvian-like, clothes all dyed black. I think it was called We Only Come Out at Night. And because we needed money we threw a party that season, too, between the third and the fourth – the party was called Dark Dancer. We thought, “Oh, if we are lucky 100 or 200 people will come.” It was crazy, people kept coming. It was in a crappy club in Antwerp and the only thing we did all night was, every hour, take the money back to the company offices. We were too scared we’d lose it.

The third video is the one when they walk down the stairs at the beginning, hanging out. Basically, they’re always hanging out.

Why am I telling you all this?

“Because we needed money we threw a party that season, too, between the third and the fourth [video] – the party was called Dark Dancer. We thought, ‘Oh, if we are lucky 100 or 200 people will come.’ It was crazy, people kept coming. It was in a crappy club in Antwerp and the only thing we did all night was, every hour, take the money back to the company offices. We were too scared we’d lose it” – Raf Simons

AF: No, I’m into this. I love this.

SF: I’ve never heard it before.

RS: This was all a very long intro to say that, even at this point we were like, “Jesus, the production on these videos.” It took so many days – days of shoots, a week of editing. So we said, “Maybe it would be easier to just show.” We were so naive.

To come back to the first show [Autumn/Winter 1997], I do think it relates to the last show. I never really thought about the first show when we did the last show, by the way – but it was the same kind of mood, the feeling that lots of people could just enter. The first show, the space was small. It was in a youth club-slash-underground theatre in Paris. Crappy. I heard after the show there was a fire inside.

The backstage was upstairs, there were these little rooms where we had to change the boys – I think at least 12 silhouettes never made it onstage because the boys were just not dressed in time. Everything was inspired by English and American schoolkids. The show was a mess. But of course people didn’t realise.

SF: I think that’s interesting because, in a way, there was the space then to have that spontaneous, instinctive bit of a mess – young, unanticipated surprise. There isn’t space for that now, but in a way what you did for your last show was to make space for it.

RS: Not to be critical – but probably, inevitably, to be critical – I think that everything became very hierarchical in terms of how brands deal with their audiences.

And I didn’t really want it for the London show. In terms of, “OK, what’s the hierarchy of the seating? Who sits where?” I just said, “Let as many people in as possible, as many as security will allow, all kinds of people.” Which was always the idea. To be close to the nature of a club instead of a show. That’s also why the bar became the catwalk, and why, right after the show, we just kept going. It was not supposed to stop. It was so related to the body and movement and dancing.

I am of course very aware that that is what I can do, because of what my brand has been for so many years. It’s not the first time I did a show with only standing. I even did a show with no light, for example [Spring/Summer 2016].

I think that people take a lot more from my brand than they would take from many of the very established brands.

SF: It’s disruptive, isn’t it? It’s disruptive of the conventional system.

RS: If I think about where I come from before I even started, it was often like that. Martin’s shows were impossible. You would never be allowed to do what he did now. Xuly Bët [Lamine Kouyaté] would just go on the street with his models. And the one thing I hoped for is that it opened a different dialogue after the show. There were friends there but there were also students.

AF: Thinking about dialogues, I wanted to ask about your reaction to people’s reactions. The feelings that people were expressing when you announced that the label was closing – there was this outpouring. Your work has always been emotional, but it surprised me how connected so many people felt to it and how they expressed that feeling. And I wonder what your reaction was to that?

RS: Total collapse. I had Sam [Ellis Scheinman, Simons’s partner] here, thank God, because it was a very difficult moment.

At the same time we danced, we had champagne – because I also felt very sure about doing this. It’s difficult to talk about the psychology because, before I started, fashion was never a life dream. And I also never really thought that I could do that for ever.

“In terms of, ‘OK, what’s the hierarchy of the seating? Who sits where?’ I just said, ‘Let as many people in as possible, as many as security will allow, all kinds of people.’ Which was always the idea. To be close to the nature of a club instead of a show. That’s also why the bar became the catwalk, and why, right after the show, we just kept going. It was not supposed to stop” – Raf Simons

SF: If you look at the people who have been brave enough to walk away – at Helmut Lang or Margiela, people who stepped back – it’s wonderful to look at a body of work in its totality, and you stopped when that work was at its most insanely great. You invited everyone in to see it, all the designers came, it was incredible. You left on a high. How wonderful.

RS: And the weird thing is that this show was not constructed as the last at all.

SF: You didn’t know.

RS: I’ve been thinking about it way longer than one season. This feeling comes up – “When should I stop? When do I think it’s enough?” It’s not a daily thought, but it’s something I have been considering for a long time. I’m also very aware of what the brand has always represented, especially I think in the past decade. And it’s 100 per cent mine. Of course there were possibilities. I could sell it ... but I don’t think that anybody would want that, without me still doing it.

If people really ask me the main reason I wanted to stop, it is because I wanted to change my life. Being independent in a small brand that is so in need of me daily, it’s emotionally, psychologically, a very different kind of situation than when I’m a creative director in a brand. When I am a creative director I know exactly what I’m responsible for. Whether it was Calvin Klein or Dior or Prada, I don’t have any pressure on me in terms of the gigantic structure of these companies and their responsibilities, human resources, employees. It’s different. When you have your own company, big or small, it’s a different feeling.

I’ve been doing both together for a long time. I loved doing my brand until the last minute, and I could probably still love it if I am honest. And I love being a creative director. But the two together really also meant I had no life.

The real reason is that I wanted to have a little bit more of a life for my love, for my parents, for my dogs, for my friends. To be able to travel and move a little bit. To not always have to say to people, “I can’t, too much work.” That’s the main reason. It was only fashion.

To contemplate on the reactions – it’s indescribable. But the decision feels like the best decision I ever made at the same time. Miuccia said something I didn’t even think about. She said, “It’s amazing. It’s yours. You just stopped the whole thing. Within two or three years, you miss it, you come back. You can do whatever you want.”

AF: That’s the first thing I said to you as well, I think – that you could do it again. But it’s also the freedom to not have to do something, season after season, to maybe work with a gallery or with an artist or something like that. That might end up being clothes or something else. It’s that kind of freedom.

I also think there’s such pressure in this moment for people to be consumed by what they do, with what they do becoming who they are. To reference people that we love, people like Karl Lagerfeld or Azzedine Alaïa, they wouldn’t separate themselves from their work. It’s actually nice to be able to give a little distance, to draw a line beneath. To consider, “I don’t have to do this until the day I die.”

RS: You hit the nail on the head.

I have never thought that this is the only thing I want to do. Never. Not one day. But I think that maybe it’s also because of what the nature of fashion became. It’s so much. The most important thing for me is just to allow myself to see this as normal.

AF: Having a life?

SF: But also, I think if you are a creator but you go from one job to another to another, you’re not actually seeing anything in life to enrich your creativity. It’s very difficult, your world becomes smaller. This way your creative vision will open up because you’ll be having more actual experience outside your studio.

“The real reason [I wanted to stop] is that I wanted to have a little bit more of a life for my love, for my parents, for my dogs, for my friends. To be able to travel and move a little bit. To not always have to say to people, ‘I can’t, too much work.’ That’s the main reason. It was only fashion” – Raf Simons

RS: It’s also partly because I still want to do something very different.

I can imagine people also thinking, “But why did he not stop Prada?” If I think about the nature of the situation, I never really intended to do it alone. And it’s sublime to work with Miuccia. It is a completely different feeling than any other creative director position I have ever had, this kind of constant dialogue. But also, the fact that it’s different, the feeling that the responsibility is really shared. That is a great feeling.

SF: I wanted to ask you about your team, because probably more than anyone else ... you had Willy, Olivier, Pieter Mulier, Matthieu Blazy. You’ve had this group of people around you, through all these different experiences, who have now gone on to do their own amazing things. How do you feel about that? I think it’s very beautiful.

RS: We are family. It’s not only the people the fashion world knows. Bianca [Quets Luzi], Elke [Bernaers], Tiziana [Luzi], they have been with me for a long time. They are the people around me, and they are all family to me.

And it was such a proud feeling, at Pieter and Matthieu’s first shows. I think I was even more stressed than them. It’s a fantastic feeling. We are even more and differently in touch about things now than we used to be when we worked together. They’re independent, they have their own businesses, but they are my two brothers. Actually I told them before the announcement – that was not so easy. But it was also amazing because their instant reactions were, “Congratulations.”

I’m aware what the brand, besides me as a person, means for them.

SF: They’ve had that beautiful experience and you still share that relationship.

RS: Absolutely.

SF: It’s very romantic actually. In a hard world.

RS: Yes. Actually, I didn’t respond to your question. Of course it impacts on me. I’m an emotional person. And it’s not that I was not aware of the impact of the brand on a certain audience, but I didn’t expect how much it meant. But then I also think I can only hope they understand me, that’s all. I’m still here.

AF: I think there’s something amazing about how your label has always been connected to youth. As you grew more mature as a person and as a designer, you kept connecting with young people. That’s something I find really extraordinary.

What do you think it is that drew people in? What do you think it is that people relate to and actually will continue to relate to? Because people will continue to wear these clothes. What do you think it is that connects with them?

RS: Themselves. I’ve always wanted to just look outside to see ... What inspires me most actually is young people and their behaviour and the way they dress. I think it comes back to themselves. Maybe they understood, I don’t really know.

I’ve always worked with what I feel. I try not to overanalyse, to ask what I should do to make it work for a certain audience. I just did what I did.

AF: It’s like people with music, that teenage fandom. The way you connected emotionally to music, I think people connect emotionally to your fashion.

RS: I felt that at the last show more than I’ve ever felt. And I could also feel that in what was written by many people in the audience. I’m very thankful for that because it is something that reinforces the fact that I made this decision. Because I think I would probably feel like a piece of shit if everybody said, “Oh, thank God they closed.” Could have been that as well.

“I can imagine people also thinking, ‘But why did he not stop Prada?’ If I think about the nature of the situation, I never really intended to do it alone. And it’s sublime to work with Miuccia. It is a completely different feeling than any other creative director position I have ever had, this kind of constant dialogue” – Raf Simons

SF: Or if you burnt out, which a lot of people historically have, doing those two different roles.

RS: I never really felt I had to stop because I didn’t know what to do any more. I think the decision was much harder because that’s the opposite of the feeling I had. I don’t want to sound pretentious, but I constantly have ideas for Raf Simons.

AF: You stepped away before – 23 years ago, you stopped designing for a year. And then came back with the Richey Manic collection [Autumn/Winter 2001]. What was the motivation then and is there any similarity between that moment and your feelings today?

RS: No similarity. I think at that time I hated being a fashion designer. The company had grown too quickly. I had a feeling that part of my young life was gone. Because in the first seasons, before we started showing, I was going out a lot – my whole life was going out dancing, techno. It was all connected. But then I said, “Whoa, this company is becoming a big thing.” We had almost 20 people employed in a timespan of two years.

I started to feel pressure. I was so young, not even 30. And it was already a very serious, established business. And then I took a break. I remember I would see Olivier Rizzo every day and a girlfriend and we would go out a lot again, and we would go to the sea and I started smoking. And then I missed it. And then I thought, “Fuck.” And then I started working on that collection and it scared the shit out of me, because I knew it was different from what we’d done before. But that’s what I felt.

AF: But it was different from everything, honestly.

RS: I also remember I asked Willy – which is something I would never do normally – to come and have a look a few weeks before we showed. I needed at least one opinion from someone I knew was going to tell me the truth. Hate it or love it.

AF: You have to tell us what he said.

SF: Yes, what did he say?

RS: Well, he’s still wearing the bomber jacket. Some people hated it, but there were also many people who freaked out. They loved it. And that was that.

SF: I think many of the fashion shows that people remember the most evoke extreme reactions, a strong emotional response. And it doesn’t really matter if it’s love or hate.

RS: I learnt to be happy with shitty reviews, I’ll say.

AF: Because of the nature of this conversation, we are looking backwards. I wanted to ask how you feel about nostalgia, both personally and culturally, because I never think of you as a nostalgic person. But I don’t want to put words in your mouth.

RS: You’ve known me for a long time, and I think I have always had a very big mouth saying the past is not romantic, the future is romantic. And I still think that. It’s complicated to say that these days, but still I need to believe that the future is amazing. I need to believe that. But I also find the past now way more romantic than I used to. There was something incredible there, and so I have probably become more nostalgic.

SF: We’ve talked in the past about the idea that you’ve got certain things you carry with you – Margiela, Helmut Lang, the colours of Yves Saint Laurent. If you see something you love, why would you throw it away?

RS: Probably in that way of thinking, I’m extremely nostalgic. Things from the past have really made an impact on me. Things that are daily with me, I think about them all the time, which is in fashion language people like Margiela or Helmut Lang, in music people like David Bowie or Kraftwerk. That is true, for sure.

Maybe I meant more that I am not so keen on making collections that have in mind a retro feel to them. Not that I never do it, I did do a collection that was very Bruegel.

“I think I have always had a very big mouth saying the past is not romantic, the future is romantic. And I still think that. It’s complicated to say that these days, but still I need to believe that the future is amazing. I need to believe that. But I also find the past now way more romantic than I used to. There was something incredible there, and so I have probably become more nostalgic” – Raf Simons

AF: I’m not sure Bruegel counts as retro.

SF: And one of the wonderful things about fashion is that now your archive will have the same effect on generations of designers to come. And you will become part of their language. And I love that.

RS: Only the new designers.

AF: Do you have a collection or collections that you consider your favourite?

RS: From a clothing point of view or an emotional point of view? But the first show ever and the last show, emotionally for sure.

As a collection, because for me it was such a disrupter of what a brand can be, the Sterling Ruby show [Autumn/Winter 2014]. It felt ... I’m an individual and I like to operate on my own. I am specific, I know that, but it also feels fantastic when you relate with another creative. To get into another mindset that isn’t mine, I need to really love what the person stands for, which was Sterling for that show. It was really the two of us doing everything. That is now the case with Miuccia.

SF: But that’s interesting too, because there’s traditionally the idea with a designer that you’re dealing with a big ego, and that’s not necessarily going to work in pairs.

RS: Yeah, I don’t have an ego in that sense. Neither does Miuccia, otherwise it would not be possible. But it’s also not that I could just do it with anybody. I’ve been very specific about it and Miuccia is very specific about it. We talked about it a lot when we started. From day one it was a natural thing.

SF: Where do you think your instinct, or desire to disrupt, comes from?

RS: That, I don’t know. I don’t really know if I disrupt. I just do what I feel like I have to do, I guess.

I didn’t really start with the intention of only doing men’s. Linda said, “OK, make clothes.” And I started to make these clothes and fit them on myself. I was 59 kilograms at that time and 184 centimetres tall, so perfect circumstances. But it was very reactive. My perception of fashion was through glamour – I could not relate. Models, for example, were for me one of the big things I could not relate to. I just wanted people. People around me and people with the right attitude. Lots of the boys we chose within the first four or five years, they were small and not beautiful in the way people looked at models.

And the clothes followed what was needed. They were very small, because I saw that the idolisation of masculinity back in the day was a big shoulder, suntan, beautiful hair. And I couldn’t really relate. I didn’t see it like that at all, probably because I didn’t look like that and people around me didn’t look like that. So it was a natural thing. I never really thought about it in terms of, “I am a disrupter.” It was just, “I don’t like that. I want to do the opposite.”

SF: I think part of your history will be that, when you started, menswear was seen almost as a poor relation to womenswear, from the point of view of ideas. You practically turned it the other way around – the gender of it is irrelevant. It was the spirit of it that made menswear influential.

AF: And when you closed, people didn’t say, “A fiscally significant brand has closed.” Raf Simons is a great emotional brand. An important brand. That’s the thing. Looking through your collections, I just thought, “This is incredible.” It was such an exercise to go through them all and just think, “Jesus Christ, the amount this has been ripped off, the way it’s been referenced.” It is an amazing thing to have a body of work that’s been so influential. Very few designers have that. And in menswear, there’s you.

SF: I think there’s really only you, Raf.

RS: I always saw the clothes only as one part. For sure, the people we worked with were as important as the clothes, the music was as important as the clothes, the attitude, the places we chose to show in, the relationship between environment and audience, that was all of the same importance for me. It was not, “Oh, I make collections, how are we going to present them?” No way. And still, up until the last moment I have never, ever in my own brand looked at a garment without music. It wouldn’t be possible. It’s so connected.

AF: I don’t even know if we want to talk about it in the past tense, but what do you want the legacy of your label to be? How would you like Raf Simons to be remembered? It’s a weird question. I’m sorry.

RS: Some questions are difficult to answer in the moment. I think from what I felt already, when it all stopped, the reactions, I could not have possibly put it into words better than other people. I’m not somebody who is really on Instagram – the label has an Instagram account and then of course lots of people around me, they’re on Instagram. So they make me see it.

One of the people who wrote things on Instagram that really made me emotional was Pieter. It made me quiet. That is very emotional because of the past, because of the many, many years together. When I saw what he wrote – I don’t know if you read it, but you can – it was very impactful. Those words, those feelings. The Raf label, it was also a family.

Maybe it’s, again, nostalgic – but sometimes we look back at things and think, “Why were we complaining? Why did we nag? It was fantastic.”

Hair: Louis Ghewy at MA+Talent using ORIBE. Make-up: Hannah Murray at Art+Commerce. Manicure: Anastasia Feokistoff. Model: Julia Nobis at Viva Paris. Casting: Ashley Brokaw. Lighting: Romain Dubus. Digital tech: Henri Coutant. Photographic assistant: Samir Dari. Styling assistants: Niccolo Torelli, Emmanuelle Bastiaenssen and Ginger Bogaert. Hair assistant: John Allan. Make-up assistant: Jill Joujon. Producer to Willy Vanderperre: Lotte Mostert. Production: Mindbox. Producer: Isabelle Verreyke. Production assistant: Liv Lismonde. Special thanks to Stéphane Virlogeux

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 23 March 2023. Pre-order here.