This article is published as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign:

It might seem antithetical, but one unexpected side-effect of the Covid-19 pandemic – and the state-wide lockdowns taking place around the world – is that we seem to be talking to one and other more than ever. Even if we can no longer be in physical proximity to our loved ones, friends, or colleagues, our desire for communication remains resilient: we make do with endless WhatsApp groups and pixelated FaceTimes, Zoom conference calls and Instagram direct messages, all to fulfill that most simple human need – to have a conversation.

One wonders what the late, great Azzedine Alaïa might have made of it all. He liked his own loved ones close to him, loudly conversing around the kitchen table in his home on Paris’ rue de Moussy. There, for dinners which stretched long into the evening, he would gather friends from the four corners of the globe – artists, models, curators, fashion editors, film directors, dancers, writers, muses, his own atelier – to share a meal, and talk. The designer would listen intently, sometimes cooking himself, and always flanked by his beloved Saint Bernard dog, Didine. Most guests would return for years, and decades, to come. It’s why, when Alaïa died in 2017, the tributes were not simply for a legendary designer of clothing – “the great couturier” he was so often deemed – but also for a friend, a confidante, a father figure.

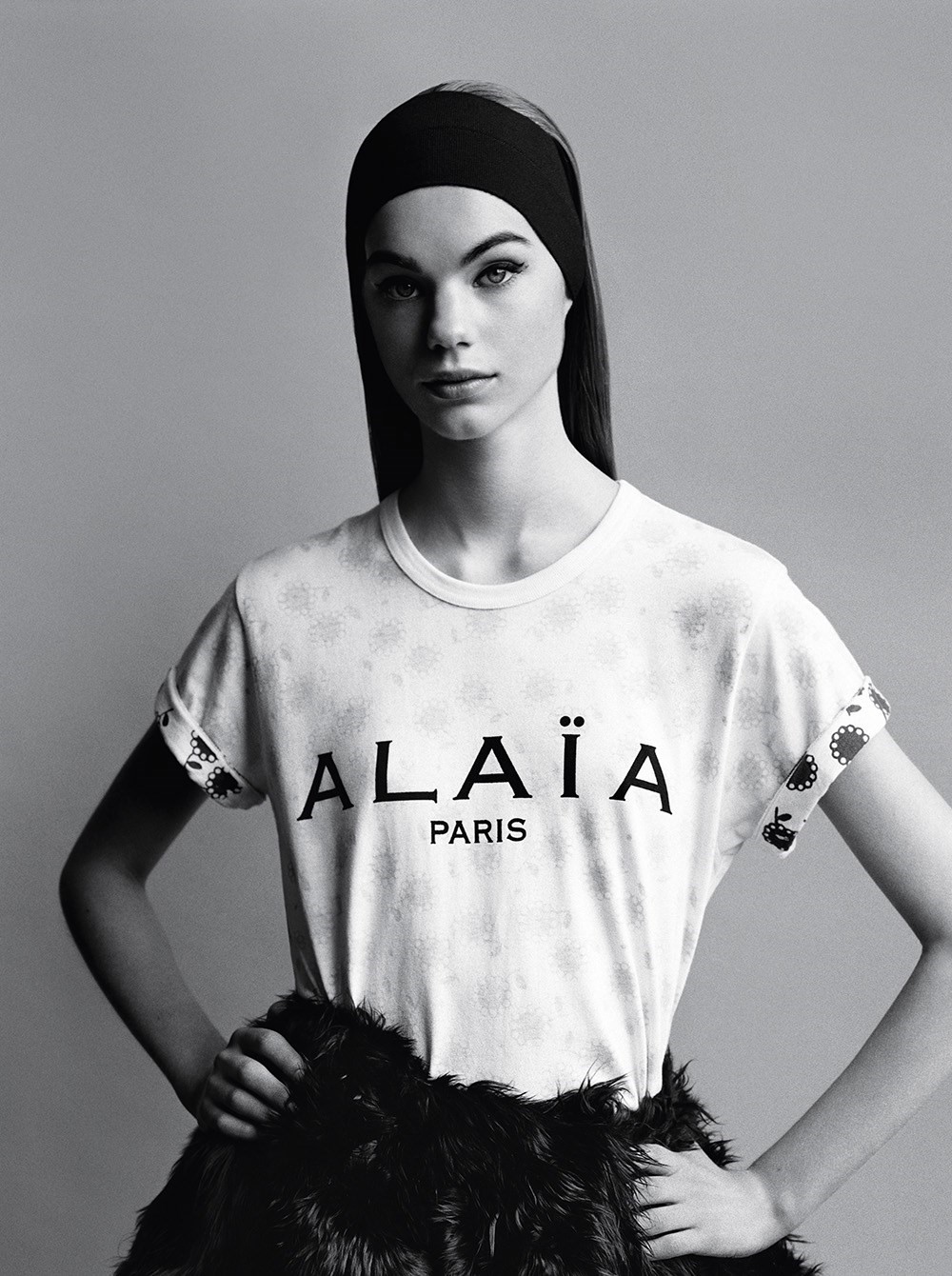

Before his death, Alaïa gathered several of his friends and longtime acquaintances to talk to one and other about the subject of time – how the pace of life seems to have accelerated in our current moment, and the effect this had on each of their lives. Together, these collated conversations form a new Rizzoli-published book, Taking Time: Conversations Across a Creative Community, created by Alaïa alongside Donatien Grau – a writer, scholar, and head of contemporary programmes at the Musée d’Orsay, who also advises on the exhibitions at Galerie Alaïa – which pays testament to the couturier’s influence through the people with whom he shared his time. “When you see the people Azzedine has collected in this book, you will understand how expansive his mind was,” writes Naomi Campbell, the model who called Alaïa ‘papa’, in the foreword.

Each coversation in the book, which takes place between in a pair of cultural luminaries from numerous fields – from Jonathan Ive and Marc Newson, Julian Schnabel and Jean-Claude Carrière to Robert Wilson and Isabelle Huppert, Charlotte Rampling and Olivier Saillard, among several others – is a thought-provoking interrogation of the moment in which we live. “Each of these interviews is like a couture dress made of words,” says Grau. “They truly are a call to be aware of, to be at ease in, and perhaps to change time. Azzedine took time for us. Now let’s take time with him.”

Here, as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign – which aims to champion culture in the age of social distancing and support projects which have been cancelled or postponed due to the coronavirus outbreak – we publish an exclusive extract from the book, originally due to be released this week (due to the pandemic, the book can be ordered but will be shipped once available). In it, Grau and Alaïa talk about the nexus of the project, technology, time, creativity and the internet in a conversation which feels stangely prescient to this new decade. “Whatever their domain, creators are faced with the same problems. I wanted to get them talking with one another,” says Alaïa. “So that they could share their experiences, and together we could raise the alarm against the increasing hysteria of our times and the way it has pent up our creativity.”

Donatien Grau: Some time ago, you spoke of gathering figures from fashion and the creative world and asking them to take a fresh look at the idea of time. We then undertook the exercise together, inviting those who are close to the house, as well as the people they chose to talk with, and sitting them around the kitchen table for conversation. During those evenings, we spoke of our concerns and experiences with respect to time. There was no audience aside from your friends and collaborators, and it made for some extraordinary moments. We’ve transcribed them in this book, which I think contains several beautiful stories. But I must ask you: What got you thinking about time in the first place? Why is it important right now?

Azzedine Alaïa: It seems to me that we’re living in an era of unprecedented acceleration. Through technology, the internet, Google, we have easier access to everything than ever before. We can feel this change in our lives: Everything’s moving faster; everything’s getting done faster. In fashion, we’ve barely finished a collection before we’re moving on to another and then another. We must continuously dream up new ideas. I don’t think ideas are so easy to come by. When I capture a good idea, I hang on to it and work it out.

The effect of all this haste and thirst for new ideas is the diminishing of our creativity. Never have we resorted to vintage ideas more than we do now. Never have we rummaged the past so much. We’re copying clothes from the 1950s, the 1960s, the 1970s, the 1980s, and these “ideas” we claim to be inventing are retreads of what has already been done. They are not new. Acceleration is killing true innovation, the kind that makes a difference.

I’m not criticising acceleration in itself and the vast possibilities it offers, but I think we must reserve a space for creation and for life. The young, caught up as they are in the acceleration, have no time for themselves; they have no time to live or create. They therefore advance without having lived, and the time comes when they find they have nothing to show for it: no body of work, no life. They’ve spent their time chasing down ideas that aren’t theirs because they’ve been rushed. They’ve not been able to enjoy the riches that life has to offer, and they’ve not been able to create what they were capable of creating.

The past is clear, we live in the present, and the future is obscure – I often think about that phrase. This present that we’re living, we must stretch it out because that’s where we exist and where we can create. It’s interesting to delve into the past, insofar as it ties in to the present. The future we know nothing about, and we mustn’t worry about it. But the present – we’re in the present, and we can act. It seems to me a mistake to delve too deeply into the past and forget the present, or to turn toward a future that is unknown to us.

“The past is clear, we live in the present, and the future is obscure – I often think about that phrase. This present that we’re living, we must stretch it out because that’s where we exist and where we can create” – Azzedine Alaïa

DG: Do you feel this applies to fashion alone or to other creative fields as well?

AA: Fashion presents the most obvious case because you sometimes have exact reproductions of recent clothes whose designers still walk among us. They might see a brand take up an article of their clothing as is, without the slightest change. And nobody makes a peep.

Still, I don’t limit my observations to fashion. It’s often said that in art or literature, an artist has become old fashioned, even as that artist continues to develop and evolve. Much later we realise that it was in that moment, when the artist was taking a little time, far outside the frenzy of the art world and the market, that some of the artist’s most important works were created.

The same goes for literature. Certain authors exist well outside fashion; what they do is very potent and will remain so regardless of trends. Trends both exalt and exhaust us. Those who get swept up in them have the insolence of youth. They’re carried along, but at some point the trend comes to an end, and then they must find the means within themselves to keep moving forward.

Above all, I believe there are creators in every domain. You can be a creator in clothes, design, literature, dance, cinema, art, even cuisine. Whatever their domain, creators are faced with the same problems. I wanted to get them talking with one another – about their life, their art, and their relationship with time – so that they could share their experiences, and together we could raise the alarm against the increasing hysteria of our times and the way it has pent up our creativity.

I don’t think there’s a difference between the lives of creators and the lives of non-creators. All are faced with the same questions and decisions. Those who create must find the space to live their own lives, and those who don’t seem to create are faced with the same problems. If there’s a lesson to be drawn from these conversations, it’s that the people who’ve delighted me with their presence ask the same questions as the rest of us: Why continue to do what we do? What matters? How should we live in this troubled world?

DG: You seem to make no distinction between a life and a body of work, or between life and work. For many, though, there is a difference between the two.

AA: I make no distinction. I live among people I work with, and they live with me. We work together, and we live together. If we are brought together by a common passion or task, then we cannot live our time in some other way.

This doesn’t seem peculiar to what I do. My house is open to my friends. They work all the time, but they can come over. The time we spend together is at once friendship time and work time. We’re always doing things together.

Sometimes people think of leisure and duty as separate: you must fulfill your duty before you can have time for leisure. But that makes “work” into a sort of prison from which you manage a brief escape. I don’t see things that way: no leisure without duty. You simply have to make a space for creation within your constraints, and make your constraints into a creation. This goes for individual life, for everyone’s particular work, and for the work of artists.

DG: But I think it’s tied to your conception of life.

AA: When new people arrive in my studio, I say to them: “I’m not going to teach you fashion; I’m going to teach you how to live.” At my side they can meet someone new every day. Those are the greatest riches, the ones I received from Louise de Vilmorin and Arletty. With them, we could always meet new people. Still today, when I wake up every morning, I wonder whom I’m going to meet. You must be open to encounters, open to your time.

DG: Some of these conversations have led to joint projects, like Adonis acting in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s film Endless Poetry, or the dialogue between Jean Nouvel and Claude Parent in the Musées à venir exhibition at your gallery, which was born of their conversation about time. How did you envisage these conversations? How are they structured?

AA: My house is open. My friends, who are my family, can come over any day. If they’re my friends, it’s because I like them personally and admire their work. The two are not separate. I’m happy to have them over. It could be to have lunch or dinner, at the kitchen table, or for an exhibition, which would allow us to show their work in a different way.

Jean Nouvel and Claude Parent’s exhibition is first and foremost a matter of friendship and respect: they had known each other very well and had worked together. Jean Nouvel has been a friend for 30 years, and our friendship with Claude Parent had been just as intense since our meeting. I cannot express enough how much I admired him, respected him, and appreciated him as a person. He is a true creator, and it was a great honor to host him and have this conversation. If we can continue that conversation, and create a space for it, so much the better. I’d like the same for all my friends.

“If there’s a lesson to be drawn from these conversations, it’s that the people who’ve delighted me with their presence ask the same questions as the rest of us: Why continue to do what we do? What matters? How should we live in this troubled world?” – Azzedine Alaïa

DG: Your fashion is sometimes thought of as being timeless. Is this because you’ve managed to impose timelessness on fashion, which you can therefore call upon to “take its time”?

AA: I don’t think what I do is timeless. I create clothing for women. I’m always looking at them. I see them on the street, and I look at young mothers and grandmothers. I’m very aware of where they are nowadays. Because I create for them, the clothes I make contain the logbook of my observations.

But it’s not every day that you can grasp a great sweep of time. You can try to capture little moments, but that’s not what survives. The great moments demand more than vintage: you have to capture where you are. For years I’ve been trying to make a straight skirt: making a straight skirt that’s right now is the hardest thing in the world.

For me, timelessness does not exist. It simply depends on what time you take an interest in. Superficial time, the short term, doesn’t interest me. It doesn’t last; it’s quickly out of date. And everyone forgets it. What matters is what lasts, and what lasts cannot be founded on too short a time. All the people we invited to take part in these conversations are people I admire, and not one of them is fixated in a short time. They’ve all managed to transcend.

DG: One last question: Why set up these conversations?

AA: I find it a shame that uncontrolled acceleration should so thoroughly sap our creativity in every domain. People often say that our era is less rich than some other, but it’s not true. There are just as many people now as before doing great, original, and new things. But they’re under such pressure – from industry, from consumption, from work – that they cannot create. As a result, everything has been separated into leisure and duty, which touches on the very idea of creation. I’m hoping we can avoid that kind of thinking: that we can think of leisure and duty as not being separate if we truly get a chance to do things and if we devote ourselves completely.

I have no advice to give. I’ve simply sought to present the stories of a few friends who are in the thick of the struggle, and who have managed to construct their time, so that people can see that it’s possible.

This is just a beginning.

This extract is taken from Taking Time: Conversations Across a Creative Community by Azzedine Alaïa with Donatien Grau, which is available to order now from Rizzoli’s online bookstore. Copies will be shipped once available.