It’s a late 20th-century coming-of-age story as old as time: riding through the roads in an old Fiesta, pressed up against each other while trying to skin up, arguing over whose tunes to put on. For so many, those car journeys, those bonds, are the defining days of their formative years, the blissful purgatory between adolescence and adulthood. Nothing to worry about, nothing to do.

Junglist was written in 1994 by 20-year-olds Andrew Green and Eddie Otchere, who used the pseudonyms Two Fingas and James T Kirk respectively. The fictional story arcs over a long weekend, following the characters Meth, Biggie, Q, and Craig as they find their way through south London, bunnin’ weed in a Ford Cortina, talking about girls and going to jungle raves; a crew of four young men in the process of finding themselves.

The book is an engrossing artefact of mid-90s urban life in Britain’s capital, weaving a tower block tapestry that feels as accurate as any documentary, a tale of teenage rebellion burning brightly amongst the ashes of Thatcher’s reign. But crucially – and no doubt because it was written by post-teenage authors – it captures the unmistakable freedom of youth that nothing can contain or restrict, no matter how claustrophobic the city. Junglist doesn’t just allow you to hear the sound of a subculture through its pages, it implores you to feel it.

Jungle exploded in London in the summer of 1994, a thrillingly raw, alien, sample-heavy sound that reflected the riotous uncertainty of the era, birthing a generation of amateur machinists pushing their Ataris and Akai samplers to what sounded like breaking point, selling their records cash-in-hand out of car boots, raving in derelict space. Jungle was a multicultural movement but undoubtedly Afrofuturist at its core and Black in its roots, the tunes living on as time capsules of inner city life, inner city pressure in late-millennium London. “By fusing elements of science fiction and horror, jungle constructed its own Afrofuturist and cyber-gothic sonic fiction, set in the derelict arcades of a near future populated by millenarian rastas, cyberspace cowboys, voodoo loa and malign shape-shifting entities,” wrote cultural theorist Mark Fisher in 2011. The first sentence of Junglist describes the sound as “a transformer banging its head against a wall.”

Green and Otchere grew up on council estates in Vauxhall and became friends at college in Hammersmith, bonding over comics, films and music. They began writing for the now-defunct Black lifestyle mag Touch as they’d figured it was the best way to get free music and clothes (not wrong). An editor called Jake Lingwood had started commissioning a series of novel-length subculture explorations called Backstreets, and rang the duo to ask them if they’d consider writing one. Despite the fact that they certainly weren’t novelists – Otchere wasn’t even sure he’d read a whole book from start to finish – emboldened by the arrogance of youth they agreed to do it.

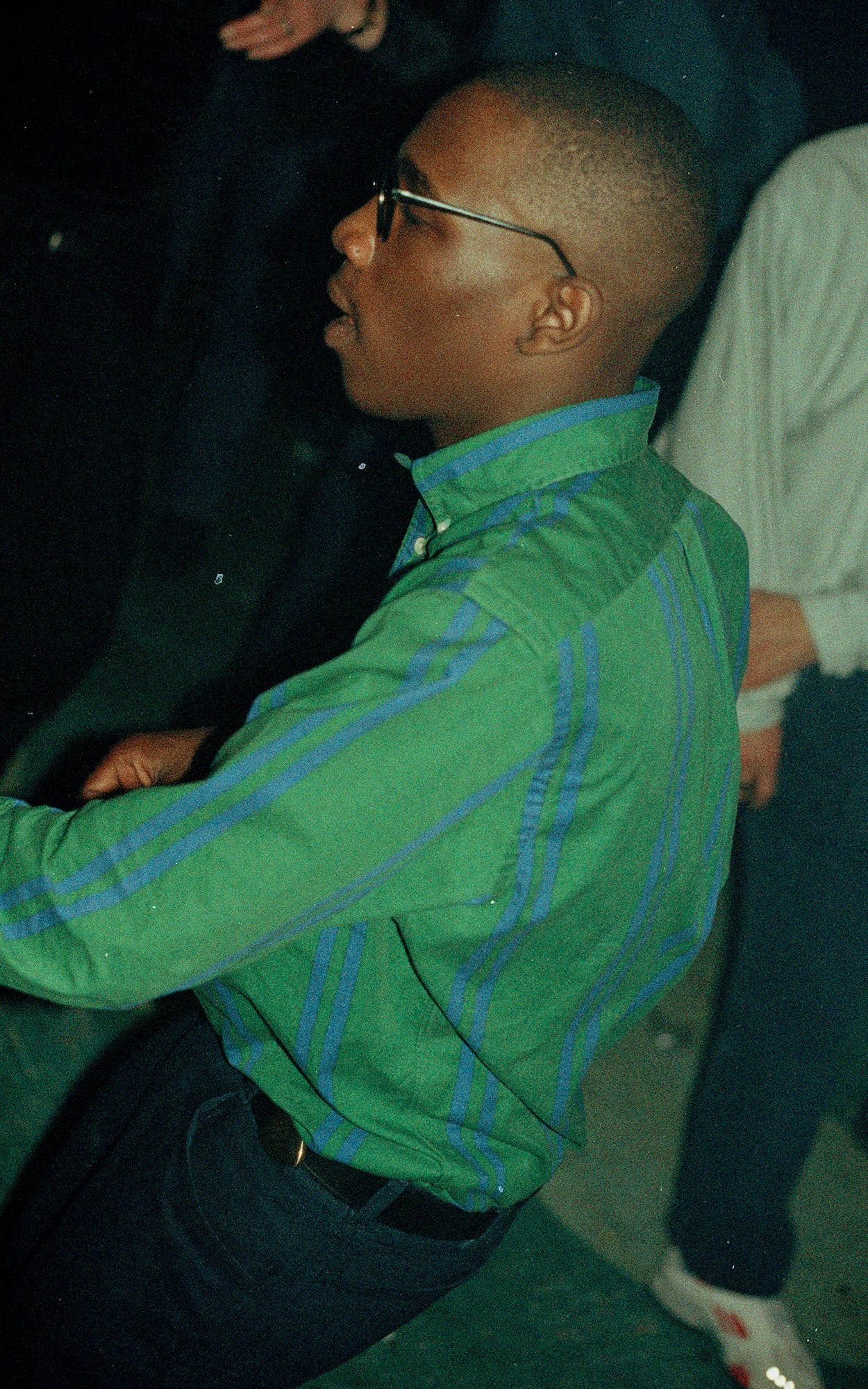

Junglist was not a commercial success, selling poorly, although according to the book’s foreword, written by Sukhdev Sandhu, it was reputed to be the most stolen book in London’s prison system. Green found a career in television, Otchere became a leading hip-hop photographer, shooting iconic portraits of stars such as Biggie, Aaliyah and RZA. The two are still close friends. In anticipation of Junglist’s reissue over 25 years later by Repeater Books, I spoke with Otchere about all things jungle, a genre the pair described as “the lifeblood of the city, an attitude, a way of life, a people.”

Thomas Gorton: What do you think attracted you and so many other kids in London to jungle at that time?

Eddie Otchere: I think it was that industrial sound, something that’s a bit more closer to our urban experience and slightly more techie, more twitchy. I didn’t go to a church where they had really nice music. I just heard sirens and Concorde flying over my head and it felt like it mirrored that industrial experience.

TG: It’s unusual to co-author fiction. It happens, but it’s still unusual. I’m interested in the process – how did Junglist come together?

EO: Myself and Andrew had already been working together, writing the junglist column for Touch. We’d tag team together a lot – I’d take pictures, he’d shoot. But ultimately, we were sitting there conceiving stories.

And so when the commission for Junglist came through, I went to a book publisher, sold some pictures and insisted I could write a book. I knew from that moment, walking out the publisher’s house calling Andrew going, “right, we’ve got a book to do, the contracts will be coming over in a minute, can you deliver a few thousand words by the end of next week?” ... I knew he could because Andrew is incessantly writing. My job was essentially just to be an editor and piece it together, either make it make sense or not make sense. We turned our weaknesses into a strength in the fact that neither one of us had studied grammar at all, we felt that grammar was an authoritarian sort of system there to oppress our language. So we didn’t learn that shit. So ultimately we were free in how we wrote or how we approached things.

Andrew wrote the bulk of it, I wrote in intersected pieces, that sort of drifted off and allowed space in it. My ultimate influence at that point would have been the poetry of Sun Ra. That’s the thing that drove me to write.

From my perspective I could write more poetry and just freeform – get high and write. With instrumental music, particularly, once your mind gets in it and it sinks into the groove, you naturally start putting words to it, start picking up on the colour vibrations, or the vibes of it. When I started writing, I used to see streams of consciousness opening up in my mind, and then you’d get home that night and just hammer it out on a keyboard.

It’s very much a case of the two of us experiencing the same things in different ways. Much of the stories you see in there, we were both in those buildings at the same time. The people that we’re talking about are mutual friends of ours, and the stories of how we used to rave back then, and our mums’ cars and conversations in kitchens. We were there to just structure it together within this context of going out, trying to find the next rave and not looking to pay, because you want to be on the guestlist.

TG: Even though it took off in the 90s, jungle still sounds futuristic and cyberpunk to me …

EO: I still hear jungle in so much post-jungle music – it’s in dubstep, garage, proper drum and bass. It’s a lovely thing to hear when it pours out of the studios, because you remember the relationships we had – the radio stations, the dubplates, the cutting houses, following certain DJs on certain nights, just to hear the new sounds live in that future. If I find the right stream, I can tap into something new that's coming from a different group of kids today.

In the book you can see where our influences come from. It’s as much about Star Trek as it is about raving and hip hop, with the characters called Q, who is a character from Star Trek Next Generation, and an author called James T Kirk, which is from Captain Kirk.

TG: You went on to have a great career as a photographer, shooting some of the biggest names in music. Did growing up on the jungle scene help you for that at all?

EO: I was going through the contact sheets of the Aaliyah shoot the first time we met Aaliyah – Andrew was writing the story and I was doing the shoot because we were both like “fuck yeah it’s Aaliyah innit”. We did it and it’s lovely, there’s a beautiful portrait of Andrew and Aaliyah together – Andrew’s pulling a silly face and Aaliyah is just amazing.

It was a wonderful thing having those ambitions, having those desires to be a writer, to be a filmmaker, to be a photographer, and growing up together.

After meeting Andrew, I went to New York with him in the summer. This is like ’92 out in Flatbush, sleeping in the basement. It sort of cemented our ambitions. We knew we had to make it and coming from London, especially central London, once you can survive in London, you can survive anywhere in an urban world. London ain’t no different from New York to Berlin to Paris, it’s the same mindset.

We really embraced that, we felt like ‘this what we’re about’. And not only are we coming to America, like ‘yo America, it’s amazing’, but we’re coming with our own strength, our own mixtapes. We’re coming to put our music into their machines and press play and turn it up and hurt them with it.

TG: How much are Junglist’s characters Q, Biggie, Meth, and Craig based on you guys growing up?

EO: Essentially they’re us, yeah. Myself, Andrew, and a combination of two to three other mates as well from that period. We’re all still mates to this day. There’s a wedding coming up at the end of this month and that’s going to be hilarious, because when we get back together again, we’re still 17 again. We’re still going back to that time, where we’re just dicking about trying to score, getting into a car trying to find a party.

TG: What do you miss most about mid-90s London?

EO: I miss the space, the derelict space, the breakout spaces. London in 1994 was greyer and grimier. But all that space was my playground. From when I was a kid growing up in Brixton, there were still bombed-out buildings that you could just run around in. And then when they got built up, when I was in school, there were still underground arches that you could play in. And I feel that the thing that’s missing the most – that space and that freedom to just turn up somewhere and just find a couch and dance or not dance, chat or not. That’s what I miss.

Pre-order a copy of Junglist by Two Fingas and James T Kirk (Andrew Green and Eddie Otchere) on Rough Trade.