This article is part of an ongoing series on Michael Clark, tied to the Barbican’s major exhibition of the radical dancer and choreographer: Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer.

Once upon a time, Jarvis Cocker thought ballet was poncey, but working with radical dancer and choreographer Michael Clark put paid to that. Both products of relocating to London in the 80s from industrial cities further north, their paths didn’t cross until 30 years later, although Cocker does remember his younger, immature self being perplexed by a poster for I Am Curious, Orange, Clark’s 1988 collaboration with The Fall. Their creative friendship started in the 2010s when Clark asked to use music from A Heavy Nite With Relaxed Muscle, the post-Pulp project Cocker released in 2003, and grew to include live shows and new compositions for the Michael Clark Company. So, when the Barbican commissioned A Musical Response to Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer, an exclusive performance to coincide with their major Clark exhibition, Cocker and his latest band JARV IS … were the obvious choice.

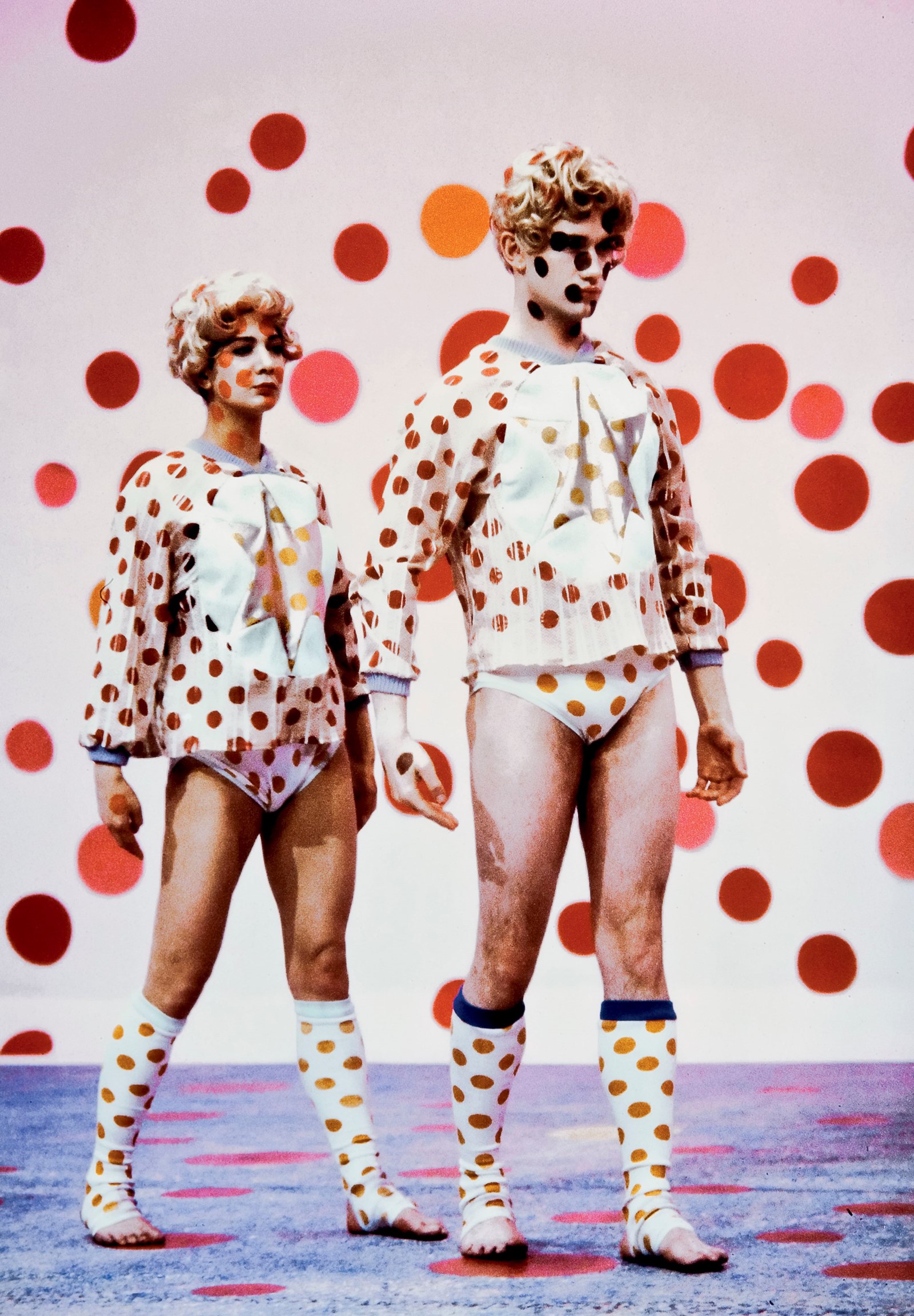

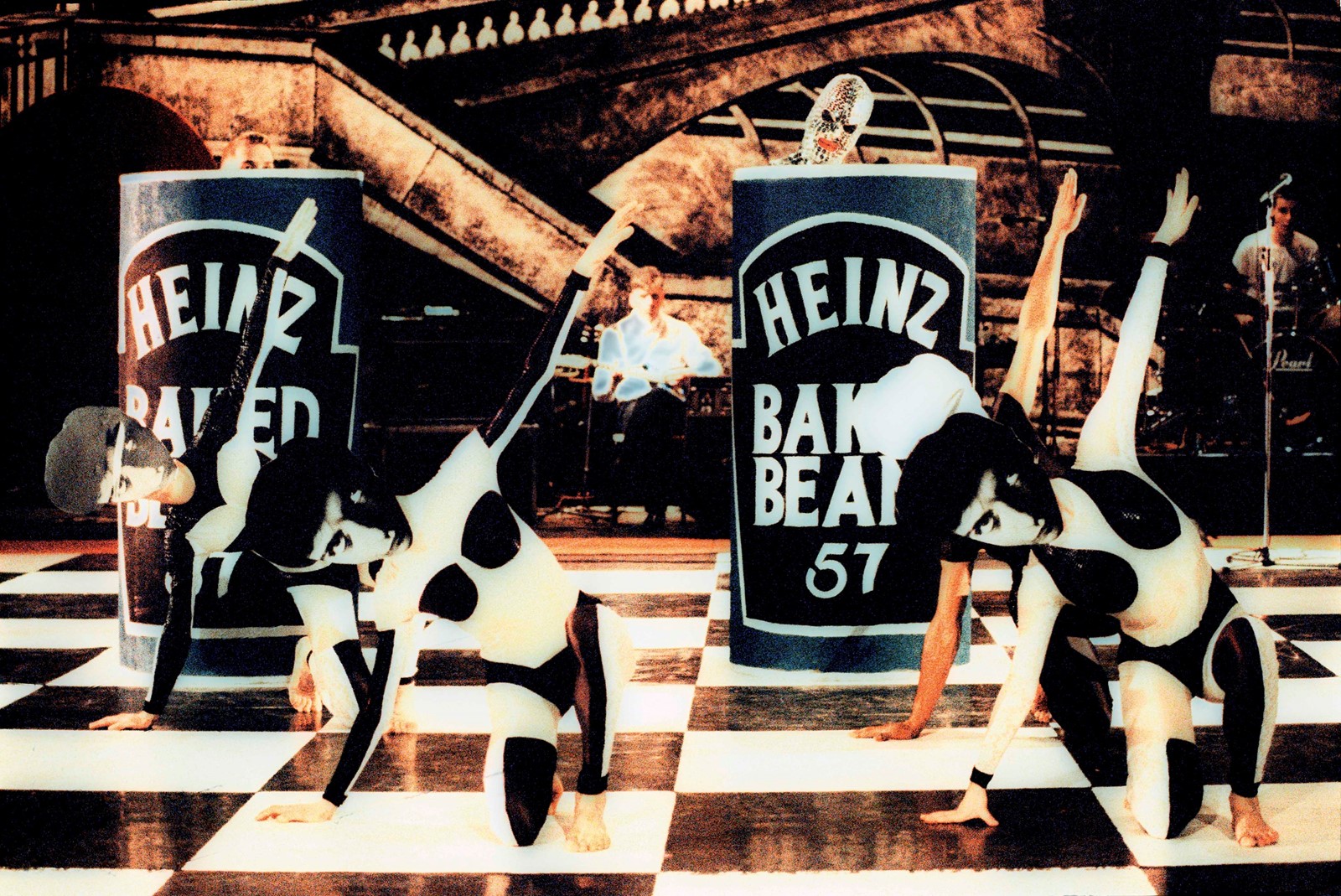

Streaming on the gallery’s website, this one-off set was captured among the installations that bring Clark’s world to life, and features tracks that Cocker picked based on his reaction to the show’s rooms. Including House Music All Night Long from the JARV IS … album Beyond the Pale, against a backdrop of Sarah Lucas’s Tits in Space, a cover of Venus in Furs by the Velvet Underground surrounded by Charles Atlas video screens, and to make amends for his earlier misconceptions another cover of Big New Prinz by The Fall, shot inside a recreation of the Sadler’s Wells set for I Am Curious, Orange.

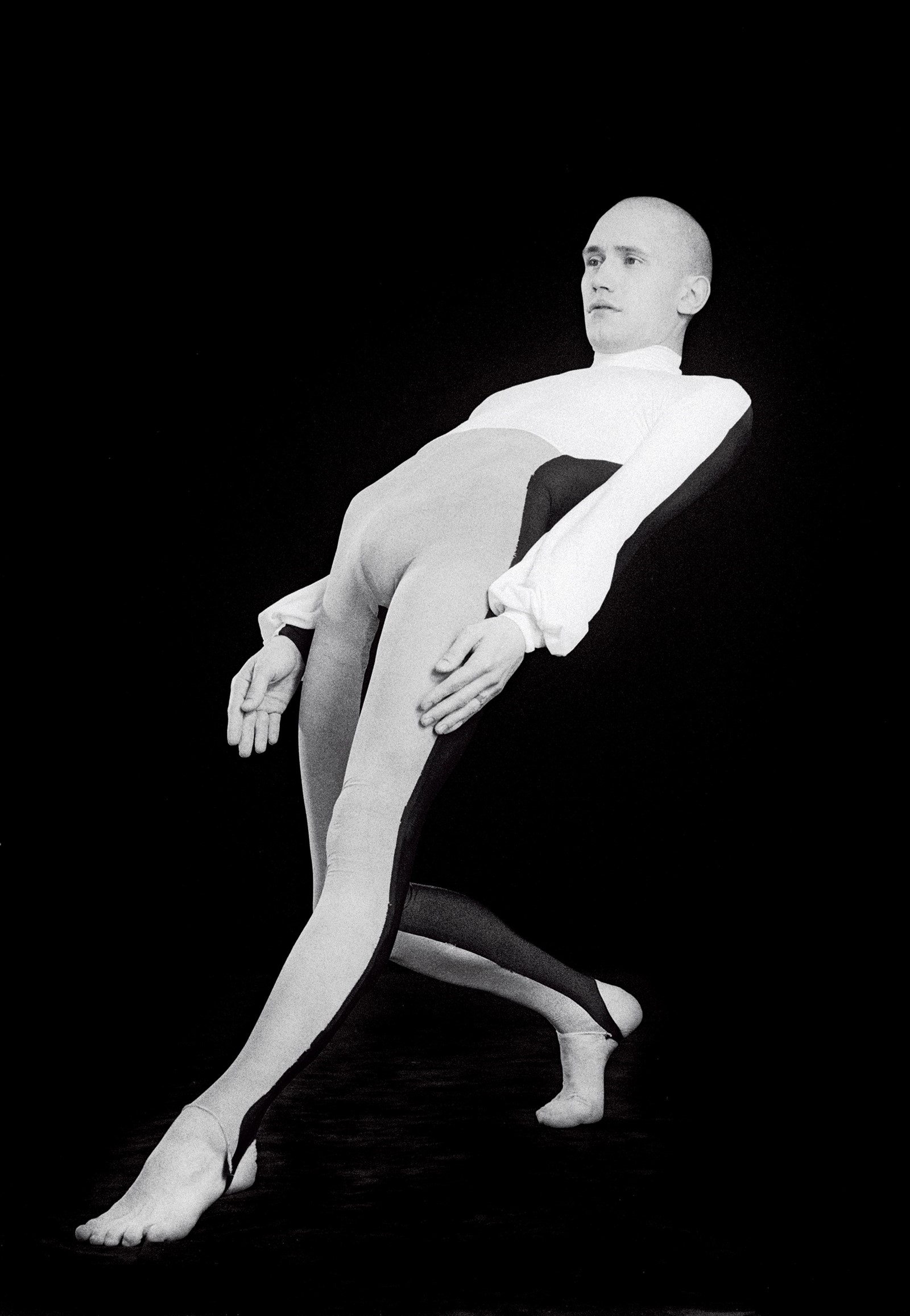

With the exhibition temporarily shut thanks to a second lockdown in place when we spoke, that gaping chasm between the hedonistic lifestyle of London’s underground scene in the 80s and how controlled and cautious we seem today isn’t lost on Cocker. “Seeing the energy of people in Clark’s films, living without concern for their own safety when we’re in a situation now where everybody’s sat at home worried about germs, is mind-blowing I think,” he says. “That’s why I feel that the exhibition came at a good time. It’s an inspirational thing to watch people using their bodies and being so alive, when to be alive is quite difficult at the moment. I’m very proud to be part of that.”

Talking on the phone from the relative freedom of the Peak District, Cocker discusses domestic nightmares, glittery pop music, and how if dance is the language of the human body then no one speaks it better than Michael Clark.

Ben Perdue: How did you first come into contact with Michael Clark and his work, were you aware of him in the 80s?

Jarvis Cocker: It was was quite strange really. I had a project called Relaxed Muscle with my friend Jason Buckle, who is now in JARV IS … , and we started doing music in the aftermath of Pulp. Towards the end, Pulp had been very slow, like an iceberg. Slower than an iceberg, it was a glacier. So, we made a record in the basement, A Heavy Nite With Relaxed Muscle, that cost about a quid to produce. It came out in 2003 and nobody noticed. Then weirdly, seven or eight years later, I got a message that Michael Clark wanted to use it. I thought, fucking hell, somebody’s actually heard of this record! I knew of Michael Clark obviously, but when I first moved down to London at the end of the 80s to study at Central Saint Martins, I remember seeing posters for I Am Curious, Orange with The Fall and thinking, why are The Fall doing ballet? To my then ill-informed and ignorant mind ballet seemed poncey.

BP: So that obscure Relaxed Muscle album was how you ended up collaborating on live performances together?

JC: We were invited to his show at the Barbican, where he has a long association, and it had lots of Bowie music in it. Everybody says they love David Bowie nowadays, but this was while he was alive, before everybody jumped on the bandwagon. I was just really impressed; it wasn’t poncey at all. Rock music sounded great played loud in a different kind of setting. The way people moved and how the music was interpreted really opened my eyes. I was touched, so I said Michael could use our stuff. Next, the Michael Clark Company had a residency at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, and they asked us to play while they danced. That led to more shows there, then at the Whitney Museum in New York, and we got to know him and his company really well.

BP: How did it feel to experience that dialogue between the dancers and the music live on stage, could your energy help influence their movements?

JC: Seeing what the human body can do is really impressive. I do think it’s a language, like somebody is trying to tell you something without words. When we played along with them it was nerve-wracking because their choreography is worked out really precisely, but when I’m performing on stage I just make it up as I go along. I thought I’d get in the way and fuck it all up. But they just said do what you do, and we’ll work around you. I’m not a trained dancer but movement is important to me, and I like to move on stage because that’s when you feel the music move through you. It’s like you’re expressing it. That’s similar to Michael’s choreography, he’s just trying to express his feelings about a piece of music that he really loves.

BP: Did you choose the tracks you performed as part of the response based on your favourites from previous Michael Clark projects?

JC: Kind of. I thought it was an interesting idea to be invited to do something. Relaxed Muscle have relaxed to the point of non-movement these days, so I knew JARV IS … would be involved, and I thought it could be good to do something specific, not just play songs for the sake of it. I heard they were recreating The Fall set from I Am Curious, Orange, so I already figured we could use a song from that. Maybe because of what I said earlier, you know, that I was aware of that show but because of being a bit immature at the time I didn’t go and see it. When Mark E Smith died, I heard Big New Prinz a lot, and I thought it can’t be that complicated to play so we thought we’d do that. Then a couple of weeks before the performance we had a look at the space, and downstairs I heard Venus in Furs on the soundtrack of one of the Charles Atlas videos. I’m not really that superstitious, but I think that if you walk into a room and a song happens to be playing, maybe that’s a sign.

BP: Is that how you decided which songs to perform in which rooms?

JC: Well, looking around upstairs, I was very struck by the Sarah Lucas room with this figure sat on top of a toilet on top of a ham sandwich. And then you’ve got this kind of weird wallpaper, with breasts made out of fag ends. To me that installation was like a domestic nightmare – staying in and smoking – it was kind of horrible. We’ve got this song, House Music All Night Long, about the claustrophobia of being stuck indoors during lockdown, and I thought a more mournful version of that would fit the section perfectly. So, it really was a response to the work. Then we just had to sort out the practicalities of setting up, playing, then moving everything into another room, which was quite problematic.

BP: Did you get to speak with Michael Clark at all while you were putting the response together and discuss ideas?

JC: I tried to speak to him. I thought he’d be into it, because it was a direct reaction to the show. So, I let him know that we were planning to do those two covers, just in case it might disturb him in some way. The nice thing was that I hadn’t seen Michael for a long time, and he came down on the day we were performing.

BP: What’s he like to work with?

JC: He’s a very good collaborator because he does crazy research and knows everything about you. Like he discovered that Relaxed Muscle record, which maybe ten people had bought, listened to it and worked out choreography that fit with it. But then when it comes to work, he gives you a lot of freedom, he wasn’t precious about sharing the stage at all. That’s the best kind of collaboration, when you feel that somebody gets what you’re doing and trusts you to get on with it.

BP: You both left working-class cities and came to London to pursue a career in the arts. If you’d known more about him in the 80s, do you think you’d have been able to relate or see parallels with your own life?

JC: Yeah, I think so. Michael came on one week when I was doing my Sunday Service show for BBC Radio 6. It was David Bowie’s birthday and I knew he was obsessed – Bowie had inspired him to dream about something else and escape his background. He chose some really obscure music I’d never heard before, like this fantastic version of Bowie singing America by Simon & Garfunkel. His first ever record was a Bowie single that you had to collect ice lolly wrappers to get. You can’t get much more pop than a record you get by eating ice cream. We’re a similar age, and if you were stuck in a backwater pop was something glittery and enticing that could inspire you to dream of doing something different with your life.

BP: Looking back at some of the other people he’s worked with you belong to an impressive list, like Leigh Bowery, Mark E Smith and Charles Atlas. What does that mean to you?

JC: That’s why I was so keen to be involved in this exhibition. It’s a pain that it’s been temporarily closed due to lockdown because in a year when people have been stuck inside, and underground culture has basically stopped, films like Hail the New Puritan show you the real picture of what living under the radar in the mid-80s was like.

BP: Are you finding lockdown difficult in terms of sharing those kinds of experiences?

JC: Yeah, but I’m not alone in that. We were set to tour and play festivals last summer. But I’m glad we released the record during lockdown, and that was a conscious decision, because a lot of people I speak to say they’ve gone back to listening to music again. Sitting and intently listening, not just having it wafting around in the background while they peel potatoes. And I think we benefited. We released an album at a time when people were ready to take notice of it.

BP: With venues shut have you managed to explore any alternative ways of performing the album live for people?

JC: We’ve been lucky with this event at the Barbican. And we also did a show down a cave. Near where I’m talking to you now there’s a village called Castleton and it has lots of caverns. We performed the full JARV IS … album from a chamber deep within the cave system there and that’s streaming now. It’s called Live from the Centre of the Earth, which is not strictly true, but it’s near enough.

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer is at the Barbican until 3 January 2021. The exhibition’s opening hours have been extended until 9pm from Thursday to Saturday. Full opening hours are: Monday-Wednesday 11am-7pm; Thursday-Friday 11am-9pm; Saturday 10am-9pm; Sunday 10am-7pm; 24-27 December Closed; New Year’s Day 12-7pm.