AnOthermag.com’s book columnist Ana Kinsella has mixed feelings about the literary award

Autumn would be my favourite time of year, were it not for the existence of the Booker Prize. I have nothing against the prize itself, but as the announcement of the winner approaches each year, I have to field many questions from people who were seduced by a bookshop display table and have now read at least one book from the shortlist. Have I read Milkman? Because they have. And what did I think? I coast through the other nine months of the year in relative comfort, with nobody asking for my opinion about books I haven’t read. But autumn is fraught.

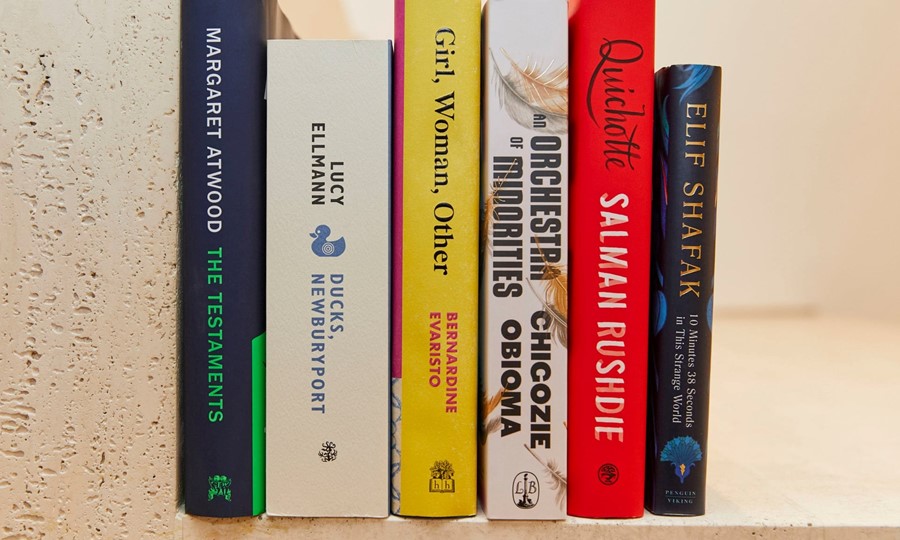

This year I decided to prepare myself. I bought some extra Audible credits and got stuck into the shortlist. It was enjoyable, at first. It was a way to get to some books I mightn’t have read otherwise, like the polyphonic anthology novel Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo. But when I realised, halfway through the list, that every novel I’d read from the list had a graphic scene of child abuse, and that each scene was used to advance a character’s depth or the novel’s plot in some meaningful way, I figured it was time to take a break.

I’m not sure why we feel such an obligation to read from the shortlist each year. Is it just because the Booker is the biggest prize in the UK? Is it a dependable sign that the shortlisted books must be good, or at least worthy, by some objective measure? When I studied English at university, that was sort of the idea. When one course had us read Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie, a book that won “The Booker of Bookers”, we joked that now we had read the best novel ever, so there was no need to read any more.

My bookshelves are now littered with nominated novels from previous years. Some of them are brilliant, and some not so. Most of them I’ve read not because they seemed in line with my own tastes or curiosity, but out of a sense that I should read them. After I set aside this year’s shortlist, I looked for something that would feel more like reading for pleasure than for duty: looking to the novels I’ve most enjoyed reading, and taking it from there. There isn’t much crossover with these books and the ones on the Booker shortlist: my favourites amongst the new novels I read this year – Tessa Hadley’s masterly Late in the Day and Jessie Burton’s wildly imaginative The Confession – didn’t earn a nod even on the longlist.

Then there is Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School, one of the best novels I’ve read in years, and one whose value probably can’t be measured in prizes. Lerner’s previous two novels stretched the limits of convention and genre, and helped earn him a MacArthur Fellowship, the esteemed prize known as a Genius grant, given to people doing important new work in any field. The $625,000 he received doesn’t make those novels, 10:04 and Leaving the Atocha Station, any better. And I thought The Topeka School was brilliant not because of its prestige, but because of the precision with which it captures gender politics and white male aggression. Lerner writes of a Kansas family very similar to his own, and he uses voices that share similarities with his own psychologist parents to tell multiple stories in the same orbit. It’s a novel about education, politics and what it is to be a teenager, but more than anything it’s a novel about the moment we’re in right now – a world where the impotent rage of the middle-class white man has become the dominant force in politics and society.

Reading The Topeka School was a reminder of what it is to read for pleasure – to follow the tracks laid by novels you love, and see what else you might find. By the end, my mind felt expanded the way it might after a wine-fuelled conversation with the smartest person at a party.

The Booker Prize jury have their own motives in choosing a list of books; for one thing, in 2019, issues of representation mean it’s vital to feature authors from diverse backgrounds not adequately served by the publishing industry. At a time when women’s rights are under threat around the world, it might be important for them to choose novels that highlight the violence that happens to women and girls, in order to maintain relevance. But the jury’s motives aren’t ever going to be the exact same as my own reasons for choosing a novel to read, nor yours, and nor should they. The British public loves to complain about the Booker Prize, and every year the jury has to contend with accusations of elitism or imperialism, homogeneity or a simple unwillingness to take risks. As a reader, all I have to do is find a book I might enjoy reading.