The story of Dennis Hopper’s Out of the Blue is also the story of a teen actress whose brief career was an unforgettable punk gesture – and Sevigny is championing its restoration and re-release

Girlhood Studies: How has visual culture shaped ideas of girlhood? In a new column for AnOthermag.com, Dazed’s editor Claire Marie Healy considers overlooked moments of coming-of-age on screen.

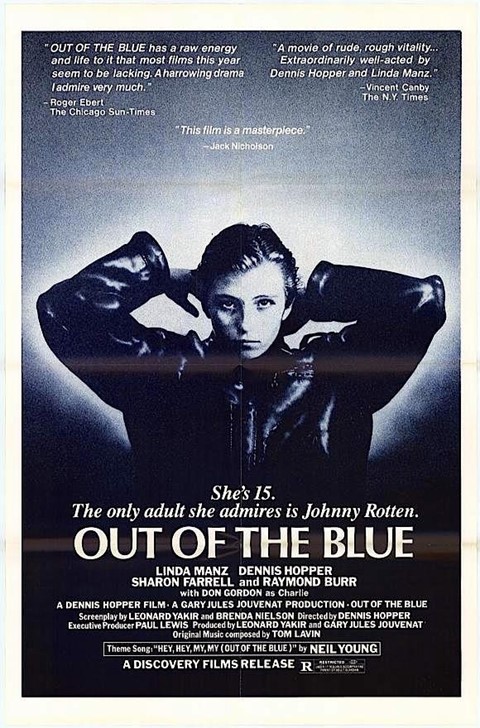

Is it better to burn out than to fade away? Yes, goes the refrain on Neil Young’s lips in My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue), the song which soundtracks Dennis Hopper’s 1980 cult classic, Out of the Blue. The same question lies at the heart of the controversial visionary’s masterpiece, which stars Linda Manz: the androgynous New Yorker who brought a raw, exposed kind of girlhood to screens like nobody else had, or ever would. That she did so over the course of leading roles in only two movies – Days of Heaven (1978), as well as Out of the Blue – is all the more incredible. But while the former has been widely watched in the years since, Hopper’s cult classic has been incredibly hard to see. Today though, figures like Chloë Sevigny are championing its restoration and re-release: more than just an exercise in nostalgia, the mission to do so is a tribute to the film’s everlasting relevance for any girl who has ever wanted to escape her environment.

A brutal record of dysfunction across generations, Out of the Blue follows the exploits of Cebe, a 15-year-old delinquent whose alcoholic father Don (played by Hopper) is serving time for crashing his truck into a school bus full of children – while Cebe was in there with him. From there, the film details the dissolution of Cebe’s parents – her mother falls into drug addiction, and Don goes back to his old ways when he is released from prison – but also the lonely exploits of the girl at the film’s centre. We watch Cebe run away from home, hitchhiking and wandering the city; whether impromptu-performing onstage at a punk show, crashing a stolen car or shoving ice cream into another girl’s face, her interactions with the world at large crash and clash like the cymbals on her drum set. Like all true-blue punks, Cebe’s voice operates at one volume – loud – like she’s trying to prove she exists.

But there’s a quiet magic to Cebe’s moments alone. Watching Manz kill time feels somehow hypnotic, her every glance and movement a key to the scared child behind the punk bravado. Her long face, solemn in concentration as she sets aflame an image of Elvis on his wedding day in twisted tribute, is somehow very old and very young – lived-in, but childish. She hugs her teddy, and sucks her thumb; even her punk proclamations seem naive. “Subvert normality! Pretty vacant, ey?” she brightly repeats into a walkie talkie in one scene, like she’s proud of her one-line in the school play – except, she’s broadcasting to bemused late-night truck drivers from the shell of the lorry where her dad nearly killed her.

We don’t actually see Cebe in school until the final 20 minutes of the film. This feels deliberate: seeing this teen-girl character being sent to the principal’s office, like every other ‘rebel without a cause’ in the movies, starkly reminds you how delinquent girls are actually always seen by other teenagers. (That is, without the useful context of the home environment that formed them.)

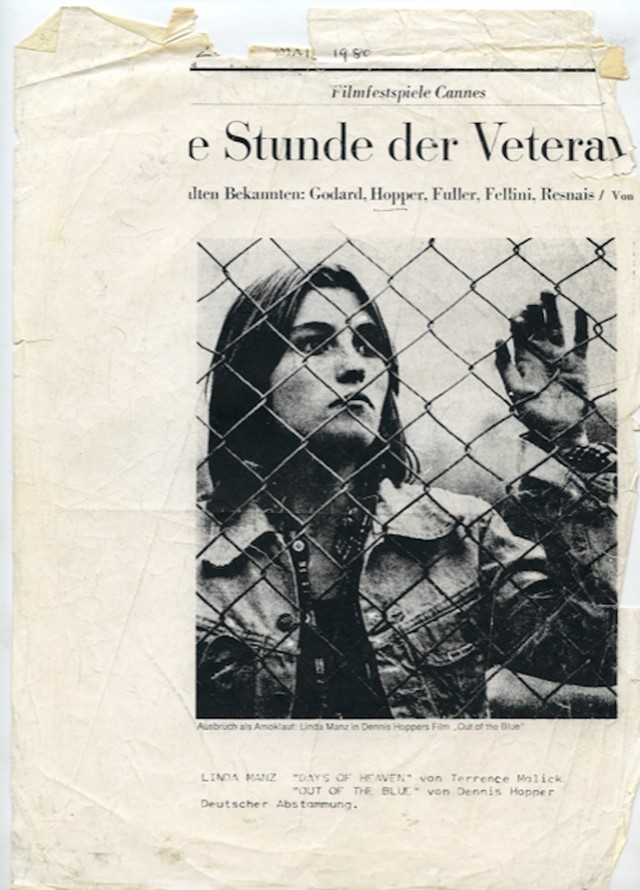

With its dark depiction of a family mired in abuse of all kinds, the picture practically fireballed into 1980’s Cannes Film Festival, where astonished, booing audiences ensured it would slip through the net of history in the years to come. If the raging nuclear family at the movie’s core seem hell-bound, Out of the Blue has been obscurity-bound.

For those who did manage to see the film, Manz’s performance has been an inspiration, even a lifeline. For Chloë Sevigny, writing on her Instagram last month, Cebe is “arguably one of the best teen actresses ever portrayed on screen”; interviewed by Paper magazine back in 1995, she even said she wanted a career like Manz’s. “As for acting, I’d like to have a career like Linda Manz. She’s my favourite actress. She did three movies and all of them are masterpieces, except for The Wanderers. Now she lives in a trailer park with three or four kids, I think. But I’d rather do that than do ten movies and make millions of dollars and have them all be trashy films.” For Natasha Lyonne, herself a child star, watching Cebe as a teenager helped her feel less alone. “The world at large doesn’t always make sense to me, and there are safe havens,” she told Interview magazine in 2013. “Linda Manz in Out of the Blue is one of them.”

I first saw – and more importantly, heard – Manz in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven. She stars as the younger sister of Bill (Richard Gere), a steel worker on the run who seeks work in the Texas Panhandle with his lover Abby (Brooke Adams), where they plot to trick the wealthy landowner out of his fortune. After Malick spent two years trying to make the narrative flow of his film work, Manz’s own voice provided the solution: as an experiment, he asked his lead to watch the film’s scenes, and simply describe what she saw. The result goes beyond narration, opening up the events of the adult world through the eyes of a teenage girl, exposing the magic and human frailty underneath it all. It’s a voice to make you shiver. (At one point, she whispers, “Sometimes I’d feel very old, like my whole life is over, like I’m not around no more.”)

The fact that Manz practically took over the films she worked on – becoming their magnetising force in a way she was never supposed to – is resounding proof of her influence. Just like in Days of Heaven, her role in Out of the Blue was never meant to be so central. Originally envisaged as a cheesy made-for-TV movie with another director, The Case of Cindy Barnes, Hopper took over the direction two weeks into filming, redirecting the film’s focus onto Cebe herself, changing the ending and adding the crucial punk rock elements. Hopper, himself in the midst of his darkest, most drug-addled days, doubtless invested the character and the mood of the movie with his own experience. But without these events, we may never have been given the gift of Elvis-humming, chain-smoking, trail-blazing Cebe – or even the nihilistic conclusion to her story, another Hopper addition. “It’s a punk gesture,” says Cebe as she lights the fuse on the film’s final moments. “There’s nothing behind it.”

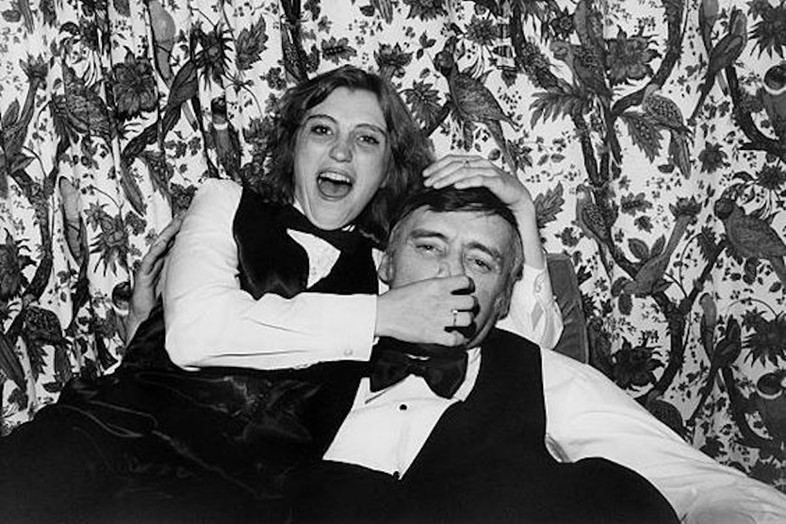

In the end, the story of Out of the Blue goes a little bit like Linda Manz’s career. With the other roles available to her at that time – like a part in a short-lived sitcom that got cancelled, Dorothy – her raw power would have only been diluted over time. Her working-class background, not as dark as Cebe’s, nevertheless shares something of the same experiences: her father walked out when she was two, and she frequently ran away from home and dropped out of different schools. Now, when you look at post-Days of Heaven photos of Manz eating cake at Matt Dillon’s birthday party with Brooke Shields, or standing with a surfboard in People magazine, they point at the starry life she totally re-routed from. But she feels like an outsider, even when she’s inside.

In a rare interview in Time Out New York in 1997, Manz revealed why she simply had to quit after Out of the Blue. “There was a whole bunch of new young actors out there, and I was kind of getting lost in the shuffle,” she said. “So I laid back and had three kids. Now I enjoy just staying home and cooking soup.” For actress Elizabeth Karr, who has led the current initiative to restore and re-release the classic, Out of the Blue’s tenderness ultimately lies in its vision of “outsiders and underdogs trying to find a way back to normal life”; for Manz, an outsider and an underdog, she actually did find her way back to normal life.

Even the denim jacket Manz wears throughout the film, embroidered with the word ‘Elvis’, eventually becomes a symbol of Manz leaving everything behind. Emerging from her very early retirement to play Solomon’s mum in Harmony Korine’s Gummo, Sevigny asked Manz if she still had the jacket. Manz sold it to her, and it has been in her wardrobe ever since. I like to think of it as her passing the baton to the next generation of youth culture chroniclers.

With the support of figures like Sevigny and Lyonne, hundreds of donations have helped crowdfund the cult classic to its former glory. It just showed at Venice Film Festival to rapturous applause – contrary to its original reception some four decades ago – and you can expect a re-release soon. The dark product of a dark place (much of it, Hopper’s own demons), out of that chaos emerges one of the greatest reflections on the brutality of adolescence for girls ever seen on screen. It speaks to anyone who has felt outside the norm, then decides to subvert normality anyway. Why not, when it feels like nobody wants you in the first place? Hopper, directing his most everlasting punk poem, knew the power of Manz telling her own story: as in the closing moments of Out of the Blue, she is the teen actress of the 20th century who burns brightest, like an explosion.