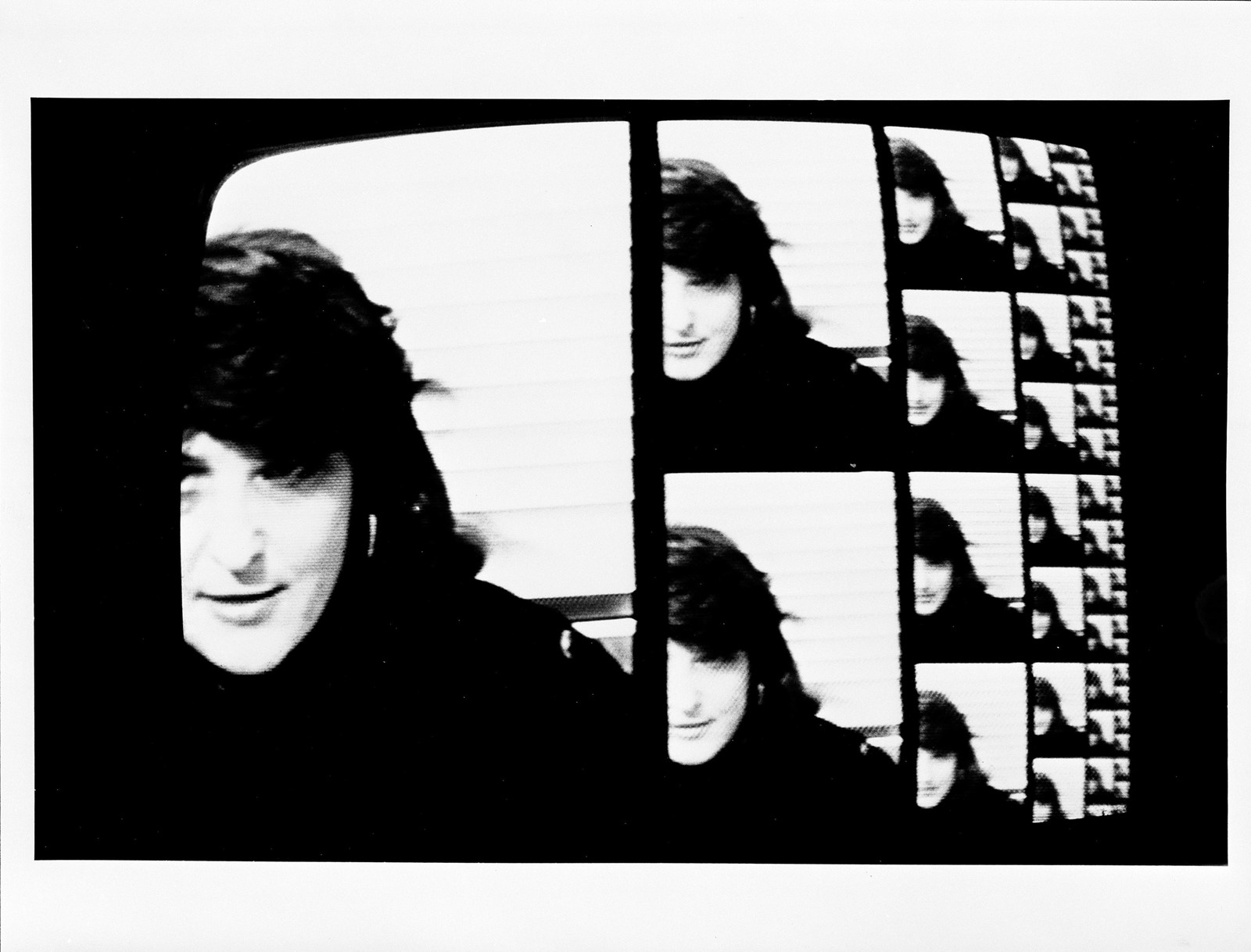

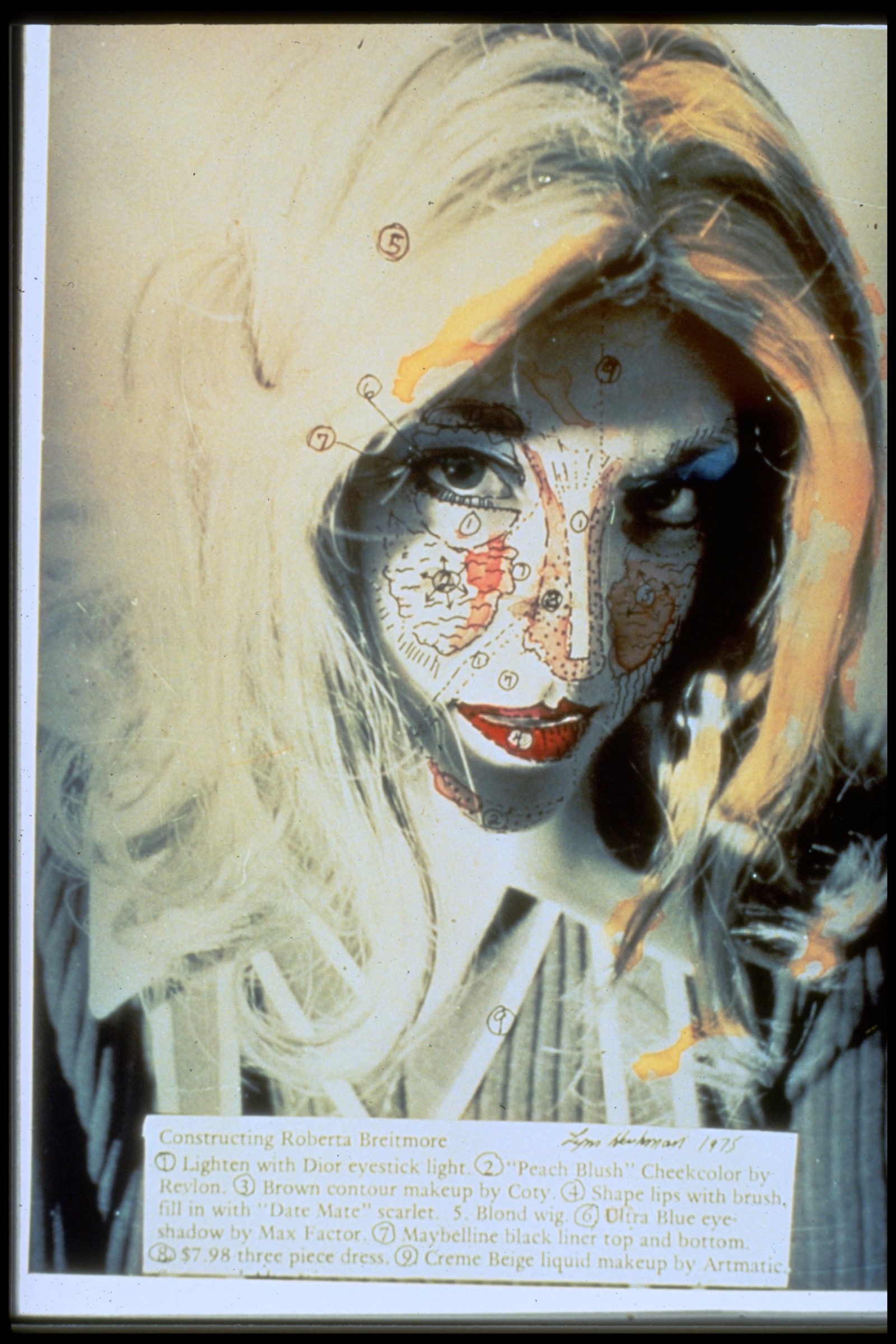

Among the rare early works by Lynn Hershman Leeson – now showing as part of group exhibition Code of Arms at London’s Gazelli Art House – is a small collage titled Looking Forward, from 1974. It shows a face in profile superimposed onto a backdrop of vertical lines, with the phrase “A Head Looking Forward” printed across the top half. As a metaphor for Hershman Leeson’s life and career, it couldn’t be more apt: with her pioneering, six-decade practise combining performance, film and biotechnologies, the artist has always been ahead of the times. A casual list of the now 80-year-old’s startlingly prescient works would have to include her disarmingly confessional videotapes, The Electronic Diaries; her “e-dream portal” AI chatbot, Agent Ruby; and of course, her years-long performance in the 1970s as alter ego Roberta Breitmore.

Fresh from a celebrated solo exhibition at Manhattan’s New Museum, in Code of Arms Hershman Leeson is honoured as part of a group of early adopters of Artificial Intelligence and machine learning in art. Though ostensibly analogue, the drawings by Hershman Leeson on display show a fascination with cyborgs and the relationship between humans and machines. It’s a fascination Hershman Leeson has carried throughout her career, including into her film work (her 2002 film Teknolust featured Tilda Swinton as a pioneering bio-geneticist, who replicates herself into three Yohji Yamamoto-clad cyborgs). But though Hershman Leeson has always been excited about the potential of new technologies, she has also always been aware of their potential for abuse. (Her 2019 short film, Shadow Stalker, starring Tessa Thompson and January Steward, explored the dangers of predictive policing and data mining.)

Here, she tells AnOther about her long career at the forefront of emerging artistic practices, her instinct to archive her own work and that of other pioneering women, and why we need to dissolve the boundaries between art and science.

Laura Allsop: Your work is so fascinating and wide-ranging, it’s difficult to focus on just one area. But let’s start with the early works in Code of Arms. What attracted you to the idea of the cyborg?

Lynn Hershman Leeson: Well, I had copied a Da Vinci drawing from the Cleveland Museum. It was a really good drawing and I wanted to show people, so I put it in a Xerox machine – which was new at the time; nobody had done that – and it got mashed. I was horrified. But then I found that it was better after that: the merging of the machine and my own drawing, even though it was mangled, [showed that] humans really were partners with machines, that we weren’t separate from them any more. So that’s when I started to think about cyborgs. The word cyborg was coined in 1960 and I think I started to do the cyborg works in the early 1960s, so I just felt like there was something coming where technology was not an enemy, but a partner.

LA: And you were hospitalised around that time, with struggles related to cardiomyopathy – was it your own physical fragility that made you think about what machines could do to help the body?

LHL: I think it was just my interaction with things like MRIs and EKGs, and having them become part of me. Once you go through that, it’s with you forever.

LA: There has been a narrative in recent years of women artists being rediscovered later in life. It must be gratifying having your work recognised but also frustrating that it’s taken this long.

LHL: Well the thing is, I wasn’t rediscovered because I was never discovered in the first place. The discovery came when I was 73 years old at the ZKM [Center for Art and Media in Germany, in 2014]. There are two parts to this: one is, what else are you going to do with your time? You don’t work to get discovered, you work to do the work. But it was frustrating because I had to take a lot of different jobs, and I saw the people around me who were a different gender selling their work and putting it in museums and getting reviewed, and all of that eluded me … It’s really a series of humiliations, being an artist – but particularly a female one, and particularly at my age.

LA: You’ve used the word entitlement a few times in interviews, and not in a pejorative way. Why do you think it’s important that younger and marginalised artists allow themselves to feel a sense of entitlement?

LHL: Because my generation didn’t. If somebody said you couldn’t show your work or somebody laughed at you, you didn’t have enough entitlement to tell them where to go or to tell them they were crazy. You had enough entitlement to keep working sometimes, but many people stopped – they were so thwarted by the oppression that they didn’t continue. So I think entitlement is confidence, and confidence allows you to do things no matter what. I think you need that force.

“It’s really a series of humiliations, being an artist – but particularly a female one, and particularly at my age” – Lynn Hershmann Leeson

LA: Did you have a sense that one day your work was going to get the recognition it deserves?

LHL: Yeah. I was talking to some museum about doing a show, but they would never give it a date, and I said “well, someday, you’re going to do it, but it’d be nice to do it when I can come to it.” [Laughs]. So I really had confidence in my work, and I really knew what was bad work. I knew what was original, and I knew that the work I was doing was completely original – nobody had ever thought about these things.

LA: Your work prefigured the way that people engage with things like Instagram, and how they perform for it. How do you find using social media?

LHL: I just use it as news communication and promotion of exhibitions. So I don’t perform for it the way I did with [the Roberta Breitmore series].

LA: Do you think about Roberta much these days?

LHL: I think about her because I’m putting together the last remaining archive of her; edition one of three. So I’m trying to organise that. But when she needs to surface she does. I don’t think about it. She just insists on coming out in some way.

LA: You said in an interview that if had you done the Roberta project later, you could have risked potential arrest for identity fraud.

LHL: For sure. Somebody tried to and they were sent to prison for identity theft. They tried to do it as an artwork to get banking accounts and credit cards, but nobody believed it was an artwork. I was lucky [with Roberta that] it was pre-computers, so nobody caught on.

LA: I was thinking about Roberta in terms of the notion of the “scammer.” It’s migrated from real fraudsters to artists proposing different personae. Someone like Amalia Ulman, for example, or JT LeRoy, who you made a short film about – they have audiences who feel cheated by a narrative they feel they’ve invested in, and are upset that it’s not actually real. What do you think about this?

LHL: Well, I think whenever you go out and meet someone new, you’re never guaranteed what’s going to happen. But with Roberta, I did limit her meetings to three because I didn’t want people to get attached to her; I didn't think that was fair. So she never saw anybody more than that. But you don’t know when you go out and answer an ad or go and meet someone that you’ve found on Instagram. [It’s] a risk.

LA: What are you excited about for the future? And what frightens you?

LHL: I think that the younger generations always find ways to survive. What’s frightening is the onslaught of extinction, but what’s exciting is that we have the possibility to subvert extinction if we use hope, human spirit and resilience. I don’t think the planet or humans have been under the kind of speeding pressure towards extinction that [they’re under] now, and it’s spiralling into a global catastrophe. But I also think that there’s human behaviour that can change that.

“What’s frightening is the onslaught of extinction, but what’s exciting is that we have the possibility to subvert extinction if we use hope, human spirit and resilience”

LA: Is there anything you might be able to tell me about the work you’re doing now?

LHL: Well, I just finished a piece with Harvard, with the Wyss Institute, that was commissioned by the New Museum, and it showed at Gwangju Biennial. It was a way of converting plastic from water, dissolving it, using electrical pulses, and also using bacteria. So that was really successful. I’d like to do something next with carbon but I haven't started it yet.

LA: If you can solve that problem ...

LHL: I mean if we could dissolve plastic from water, which we did … One of the scientists quit their job at Harvard to start his own company to do this.

LA: What would you say that you're proudest of in your work?

LHL: That it exists. That I took the risks. Much of the work I did was before the language existed for it. I'm proud of the pioneering work: The Breathing Machines were the first sound work and touchscreen anybody had done; Agent Ruby was the first AI chatbot that anyone had done. It was going with my instincts, and working until something relevant emerged. I’m also proud that I didn’t throw anything away – I threw a lot away, but there’s a lot still left over that I can show.

LA: People often think about the arts and sciences as distinct. Are you hoping, through your work, to disabuse that idea?

LHL: We have to really destroy the boundaries of disciplines, because they’re too logical. The name of my new piece is Logic Paralyses the Heart, and when you have too much logic, you don’t have compassion and feeling. You have to have porous edges, and be able to move between disciplines in order to really get a full picture. Now, with global connectivity, we’re not limited to the oppression of any one system being correct.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Code of Arms is at Gazelli Art House until January 15, 2022. Lynn will be part of a talk on the history of AI in art on November 30.