British artist Gillian Wearing first encountered the work of Diane Arbus while she was a student at London’s Goldsmiths University in 1987. “It was the way she captured people,” says Wearing of the photographer. “Their haunted eyes, as if they were somewhere between this world and another, really captivated me ... I liken it to portrait painting, and how we appreciate individual styles of painters. The same happens in her photographs.”

Over the last three decades, Wearing has emerged as one of the most prolific talents from the Young British Artists generation. Looking at the Turner Prize winner’s surreal self-portraits, in which she wears masks to transform her face into those of others – from her own grandmother to Robert Mapplethorpe – it’s easy to see Wearing as a kind of prophet. The uncanny works were exploring notions of self(ie)-making, performativity and disguise years before the arrival of social media. “I think I happened upon ideas intuitively that were interesting to me that then somehow were ahead of their time,” Wearing says. “It has been really strange to see how ideas I had years ago become something that is being explored and celebrated now in a mainstream way.”

Besides her first North American survey, Wearing Masks, at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Wearing has recently collaborated with Public Art Fund to install a life-size bronze replica of Diane Arbus at the southeast entrance of Central Park; a spot where Arbus photographed many of her subjects. Diane Arbus – which joins the ranks of Wearing’s other photographic sculptures of women, such as that of the suffragist leader Millicent Fawcett in the Parliament Square – shows Arbus holding her Mamiyaflex camera.

Here, Wearing tells AnOther about her ongoing exploration of “becoming,” her fascination with Arbus’s photography, and the changing landscape of portraiture since her breakthrough in the early 1990s.

Osman Can Yerebakan: There is a contrast between Arbus’s and your work in terms of your approach to subjects. Her lens is disarming, stripping them of their layers, while yours is about layering, adding personality and story onto the body.

Gillian Wearing: I think we are very different artists, with different experiences in life. Also for me, it has always been listening to people and understanding how our stories shape us. I had that interest way back when I studied a foundation course at Chelsea Art School. It took years for me to come up with an idea like the Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say series from the early 1990s. The series really taught me about the interior and that we should never look through the lens of someone with any preconceived ideas. Because ultimately everyone is interesting.

OCY: How do you view the difference between photographing strangers, compared to your self-portraiture?

GW: One of the first things you learn in art school is to draw yourself. I have a small oil self-portrait from the 80s in the Guggenheim exhibition. I can remember spending the whole weekend alone just painting it. My influence had been Rembrandt, because he had looked so honestly at himself, and in some self portraits he had dressed up to play with the idea of self image. As an artist, you are always available to yourself, to exploring ideas. For instance, the inspiration for Dancing in Peckham (1994) started when I saw a woman dancing out of sync to jazz. My initial thought was to ask her if she could reprise this dance for a video, but something stopped me and the frustration of that gave way to the much better idea of me doing the dancing. I was the conduit, but also it was a self portrait. Something I had seen in her I eventually became.

Getting back to Arbus, there weren’t many photographs of her: she has become this mythological person. I wanted to capture the vulnerability of her waiting with her camera to take a photograph. Central Park was a studio to her, she was brought up in the area too. She is not on a plinth declaring her presence; she is amongst the visitors. A humble soul, like us all.

“I think the fear is how much we rely on and get hypnotised by new technological mediums. By the time we have learned not to let it consume us, something else will come along ” – Gillian Wearing

OCY: Do you follow social media as part of your research today? If so, could you talk about your observations?

GW: I follow it a bit. I don’t research but I get a sense of it. Like when Instagram first came along, it seemed like the 21st-century family album. I do like the curated accounts of people who offer thoughts on what to see, read, and watch etc. Technology has always changed who we are, and of course social media is no exception – it has positives and negatives. The great thing is that it has given a lot of voiceless people a place to find a community. Having grown up in the era of television I remember debates on how it could take over our lives. I think the fear is how much we rely on and get hypnotised by new mediums. By the time we have learned not to let it consume us, something else will come along that will do the same thing.

OCY: Do you like to play with the trustworthiness of photography? Your practice seems to test its reliability.

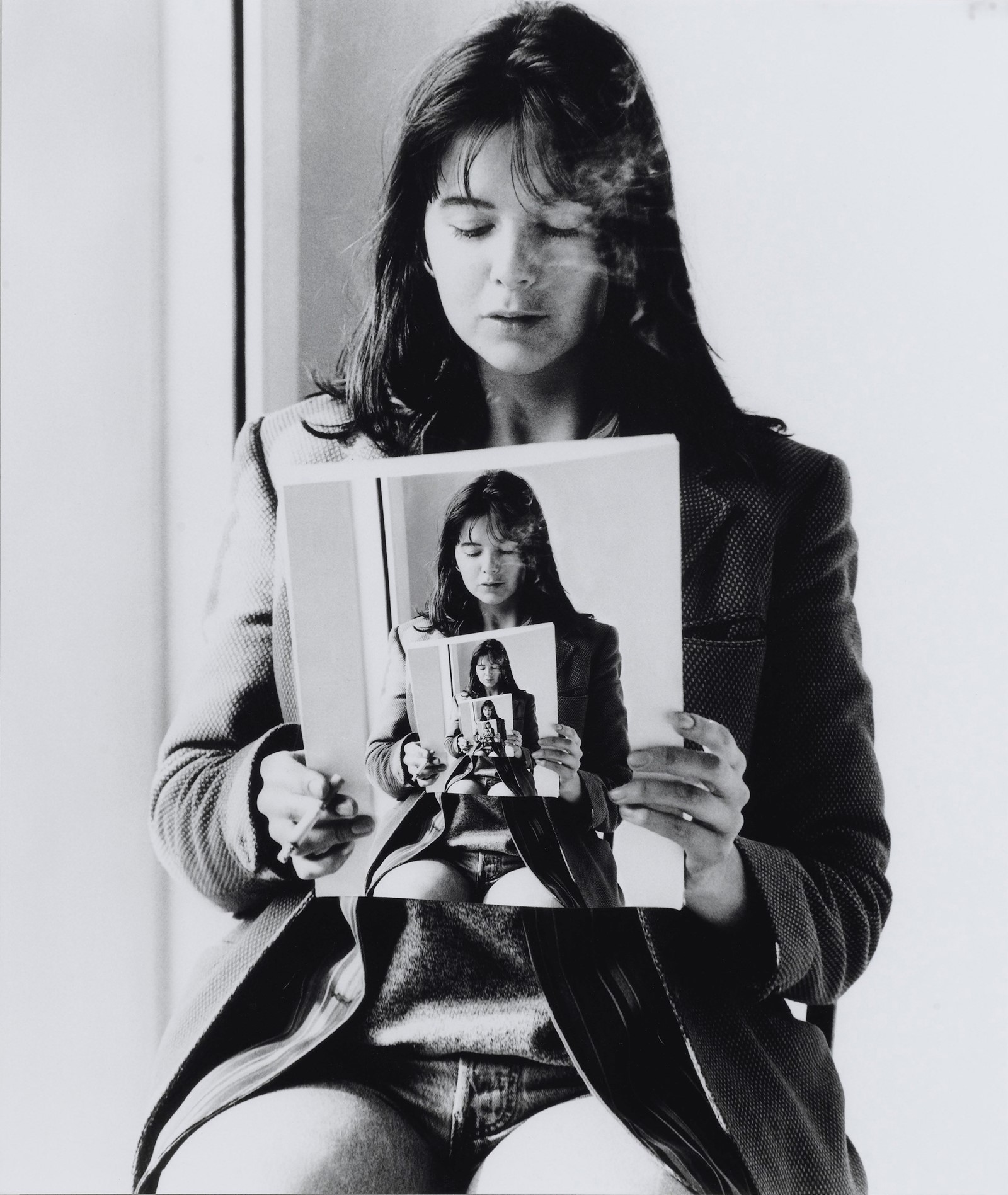

GW: I always want the apparatus of the idea to be part of the work, whether that is a sheet of white paper in the Signs series or the masks in the Album and Spiritual Family. For the Guggenheim exhibition, I exhibited my masks in a vitrine to further highlight that the work is made with real masks as opposed to digital technology. Analogue is hard for people to imagine when it comes to disguise now, because so many apps and Photoshop can change your face and physical identity – something that was unheard of even ten years ago. But there is nothing like working with a real mask. My images are large so you can get close to the detail and see the seams. I intentionally make the holes around the eyes visible so you can get a double-take between me and the façade. That quality wouldn’t work in a digital image. Also the work is performative and the mask is essential: I look in the mirror and see the person I am going to photograph myself as. My shoots take hours and when I take off the mask at the end of the day, it feels that my face is now the mask and I had just taken off my face. It’s as if the mask can reveal as well as conceal.

Throughout my work, I have been interested in what is real and what is not real. It’s such a complex question because we live mostly in our heads: we have thousands of thoughts a day, some of those thoughts are projections of ideas, of how our days or weeks might be. They are subjective, but real to us.

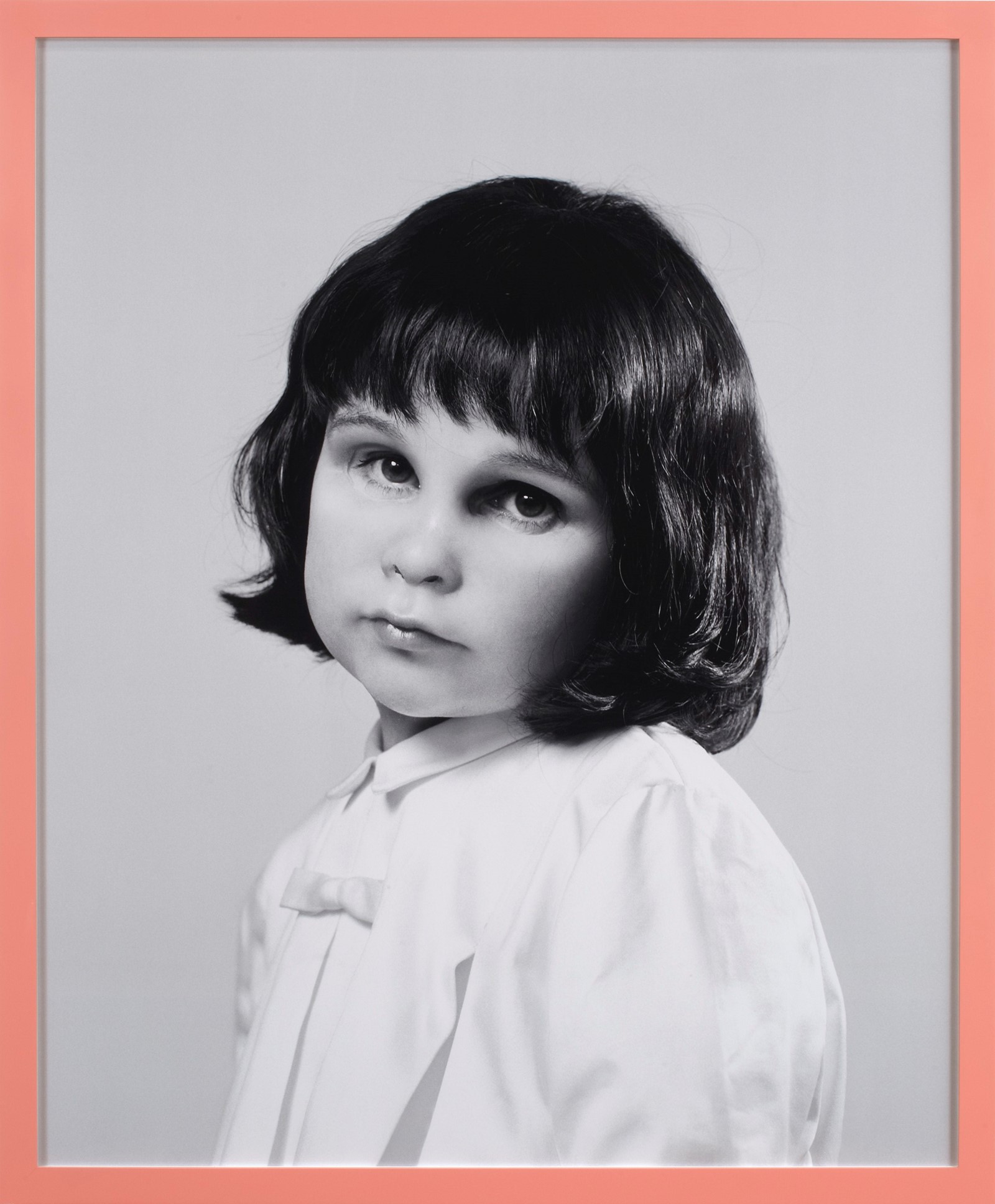

OCY: I remember seeing for the first time Self-Portrait at Three Years Old (2004), in which you wear a mask of your childhood face. There is a moment of not knowing the construction of the image, and suddenly seeing all the layering of faces. What do you think about the eeriness of this moment for the viewer?

GW: None of the masks from a distance look like disguises; it’s only when you get closer you can see they are. A sense of uncanniness comes from realising that. The masks are made with great care to detail and realism. We are used to thinking of masks within horror, dressing for fun, going in disguise to a party, something to shock and surprise people. Seeing a real detailed face as a mask is surprising.

When I was being my younger self, there is that layering of the past with the present – we carry all our younger selves around with us all our lives. In fact, I was looking at an old photo of myself the other day and thinking that was me at one point. It is so hard to imagine how time elapses in your own life and that each day you grow further away from where you started. We can be both protectors of our pasts, like a parent to them. But also there is a distance, like looking at someone else who had different life and different ideas of the future.

OCY: Do you see a challenge in exhibiting work in public compared to a museum?

GW: A museum can exhibit anything; it is literally a blank canvas so it has a huge potential for different perspectives. A public space literally means it belongs to the public, there is an engagement with how to fit in with its use. Doris C. Freedman Plaza at the entrance to Central Park is special in that it works a little like a museum under Public Art Fund and has temporary exhibits of all sizes and content. Knowing that really helps as an artist. The organization’s Artistic & Executive Director Nicholas Baume suggested placing the sculpture slightly off centre, further adding to the casualness of the piece. What I love about public work is that people who may not go to museums are introduced to art this way.

Gillian Wearing: Wearing Masks is on view at The Guggenheim through April 4, 2022.

Gillian Wearing: Diane Arbus remains on view at the Doris C. Freedman Plaza through August 14, 2022.