For the past week, the Museum of Modern Art New York has been holding daily online screenings of Arthur Jafa’s film akingdoncomethas, with the final showing today (June 9, 2020) at 5pm BST. The 2018 film runs over 100 minutes, and comprises found footage of black church services, some showing well-known figures like Le’Andria Johnson, Al Green and TD Jakes. “I believe in black people believing,” Jafa said in an interview on MoMA’s Instagram with curator Thomas Lax, in which he describes how akingdoncomethas came about following the success of Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death. “For me, that’s what it’s about. It’s about black people’s capacity to believe things with such a level of intensity that those things become singularities, they become black holes.” Here, we republish an interview with Jafa from November 2019, published on AnotherManmag.com as Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death was exhibited in Italy.

Three years on from premiering Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death, the seven-minute film that marked Arthur Jafa’s unanimously lauded return to the art world, the Mississippi-born artist and filmmaker is still dissecting what exactly made it such an international sensation. “I envisioned that it would be uploaded to YouTube and maybe I would get a job directing a commercial,” he recalls with a smile. Since the film’s opening night at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in Harlem, Jafa’s artistic success has soared further still. Between producing music videos for Jay-Z and Solange, he affirmed his status as one of the most revered contemporary artists by winning the Golden Lion at this year’s Venice Bienniale for his new film, The White Album.

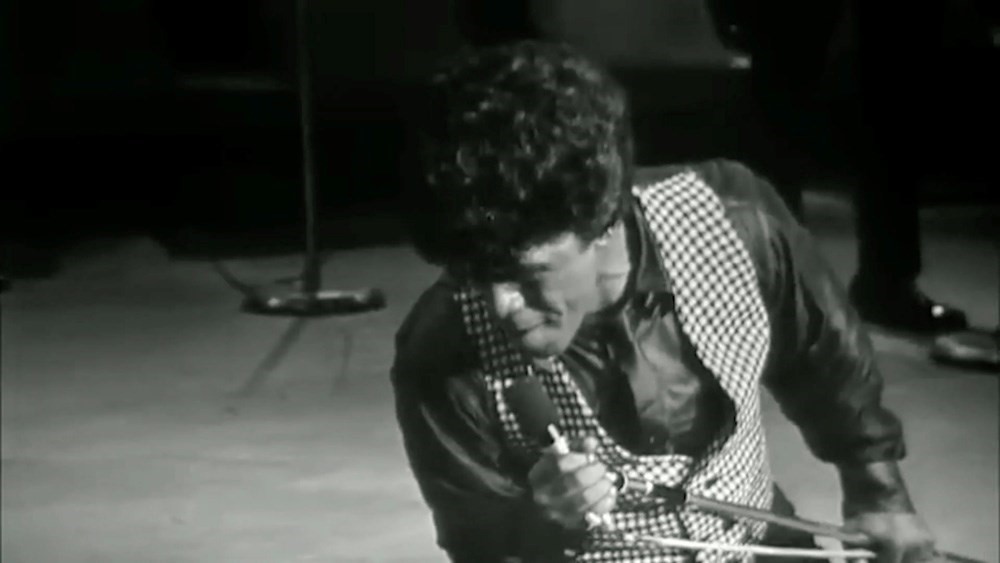

Despite their conceptual overlaps and joint use of film collage, where The White Album foregrounds a critical portrayal of whiteness, Love Is the Message explores blackness as a creative force and object of white violence. In the latter, found footage clips move rhythmically between civil rights marches, police brutality, twerking and the NBA, all to the sound of Kanye West’s gospel masterpiece, Ultralight Beam. From Obama’s Amazing Grace rendition to Derek Redmond pulling his hamstring at the 1992 Olympics, James Brown collapsing on-stage to a black teenage girl being thrown to the ground by a white police officer, it is in the words of Jafa, “a scream”, that is as difficult to watch as it is to tear your eyes away from.

With the film now showing at Turin’s Palazzo Madama following Jafa’s selection as winner of the 47th Prix International d’Art Contemporain, the artist discusses the work and everything it’s taught him since.

Finn Blythe: Are you happy to return to Love Is the Message and be talking about it again? How has its reading changed in the intervening years?

Arthur Jafa: I make a joke about it quite often, I say it’s my Purple Rain, almost as if I’m going to pull out a cigarette lighter or something [laughs]. There’s a kind of self-correcting, jaded cynicism about it just because, of everything I’ve done, it’s elicited a certain kind of emotional response from people. To a certain degree I don’t quite know what to do with that. You don’t want to discount people’s emotional responses but on a certain level too, if a hundred people have that response it sort of begs the question of whether the piece is manipulative in some fashion. So I have certainly developed, over the course of the last three or four years, a kind of reservation about that.

FB: That’s interesting because the film was met with such universal acclaim. Was there any part of that reaction you found confusing?

AJ: I wasn’t so much confused about it but I didn’t anticipate how universal it would be. I don’t know if that’s because I have a very depressed sense of other people’s capacity to empathise with black people, it may just be me, but then the question becomes, what are people responding to? You don’t really know if people are just responding to an evolved sense of empathy with respect to black people, you don’t know if people are just responding to the violence, or whether there’s something, as I said, problematic about the construction of the work that’s eliciting this kind of response. Going forward it’s made me somewhat reticent about utilising certain ... I hate to call them tricks but they are sort of tricks, I think; formal tricks.

FB: What lessons from the work and its reception did you bring to The White Album?

AJ: You know the life of an artist as I understand it, it’s really more the life of musicians, people working on albums. Elton John working on Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Brian Wilson working on Pet Sounds, you know what I mean? It’s like, you have a success and then people want to box you in on that. I think continuously about what it is I want to say, whether or not there is a space, and how do I make this space to articulate the things I find interesting in the world? Like I’ve said before, with regards to blackness I’m interested in at least two things: one is the black experience and the other is the experience of black people. Those things aren’t necessarily the same.

FB: You’ve collected images your whole life. On a general level I wanted to ask whether what you’ve articulated through Love Is the Message can be condensed into a single idea or emotion? When you were selecting clips to use, what guided your composition?

AJ: It’s hard to encapsulate. I think there’s a tendency, at least initially, to want to construct it as a kind of sociopolitical statement that dovetailed with Black Lives Matter. I guess that’s a way you can read it, but I’ve always felt there are things about it that are not so obvious. For example, people ask about Bernini in relationship to Love Is the Message. If you look at Love Is the Message from the frame of Bernini you can see how consistent it is in terms of black bodies torquing in a certain kind of way, which is one of the primary aspects of Bernini. I like to say great artworks are always serving multiple masters, meaning they’re not just creating, as a poem, beautiful imagery or saying something profound about the world or rhyming beautifully – they have to do all those things simultaneously.

FB: There’s an interesting confluence between your preoccupation with image-making and the internet. A lot of clips from the film were familiar to people of a certain age because of things like YouTube. What do you feel the currency of those viral videos is in your work?

AJ: I think the word you used hits it on the head: confluence. It’s a confluence of things because it wouldn’t have been possible for me to make that work prior to YouTube, just because of the access to archival footage. I’m very hesitant to even use that word because classically that’s not really what an archive is. Classically it means a contained body of material that has a protected access. That’s not what YouTube is. YouTube is like a free, floating thing ...

FB: And it doesn’t move linearly.

AJ: Not at all. So when people say my work is preoccupied with ‘the archive’ – I’m not preoccupied with ‘the archive’ at all. In the same way, if you’re a musician and you use certain notes, you’re not preoccupied with the archive of sound, it’s just the body of things to work with. So with Love Is the Message, the infinite body of things that are constantly going into mutual, collective access and out of mutual, collective access is what I was working with. It’s like the body of sound, it’s infinite. So it’s not about a preoccupation with archives, it’s a preoccupation with images.

FB: There’s an interesting comparison between the way viral videos, especially those of police brutality, spread through this intangible space you’ve just referred to. I recently spoke with Mark Bradford about his new paintings that visualise how riots spread across a city, from the Watts Rebellion to the Rodney King riots – which of course was one of the first instances in which footage of police brutality was circulated as a means of mobilisation.

AJ: Right. I mean Rodney King is ground zero. There’s a lot of complicated stuff that’s happening but one of them is the kind of tension around what black people have been insisting about the West since we’ve been here. That it’s violent, that it’s misogynistic, that it’s this and that, right? These things fly in the face of how the West wants to understand itself, and so we’re typically told we’re overstating it, we’re exaggerating. People would tell these fantastical tales about being put in a trash can and the question becomes, is this believable? Can we really see this? The first time someone told me they’re gonna put cameras in a phone I said that is the dumbest idea I’ve ever heard in my life, and that just shows what I know because it has transformed things on a fundamental level. It is the technological evolution of the capacity of a people to not just consume images, but to produce them.

FB: Well it means to no longer be passive, it gives agency, it’s mobilising and to a large degree, democratising.

AJ: Completely. It’s about not just hearing sounds but being able to speak. So in a sense, I think Love Is the Message certainly does operate in the space of: once we collectively have the capacity to be able to enunciate in this media space as opposed to just consuming it. In the 20th century, most people would go to see movies but people couldn’t make movies, you know what I mean? There’s a certain frisson, a cognitive dissonance that’s produced when a thing that a certain oppressed body of the overall population is insisting is true – which at the end of the day everybody knows is true – but we know there’s a power dynamic in place. It can’t be ‘verified’ because people always question the legitimacy of their interpretation; of their experiences. But now all of a sudden, here we are. Seeing is believing. It’s a kind of catalytic thing going on now in terms of a person being able to, from a minority position, a minority opinion, drop something into the pool that can catalytically transform what everybody has to collectively accept. I think that’s a little of the space that Love Is the Message is operating inside of.

MoMA is screening akingdoncomethas by Arthur Jafa at 5pm BST today, June 9, 2020.

Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death by Arthur Jafa was on show at Palazzo Madama, Turin, until November 13, 2019.