How and why do men dress the way they do today? The V&A’s new exhibition Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear attempts to answer this question – but it doesn’t necessarily provide the answers, writes Daniel Rodgers

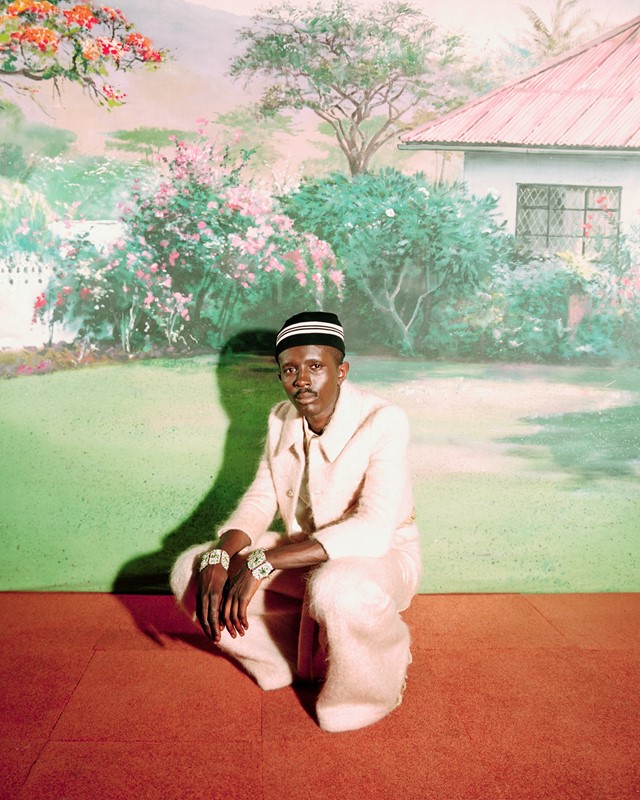

As members of the fashion press were ushered into the atrium of the Victoria and Albert museum, Kojey Radical stared upwards at an eight-foot portrait of Charles Coote, the 1st Earl of Bellamont. One of them was wearing a lime green Crêpe de Chine blouse and a rhinestone-monogrammed suit from Gucci, while the other had been styled in a salmon-pink cape and an ostrich-feathered headpiece. Born 300 years apart, both men were being showcased that night as part of the V&A’s new exhibition, Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear.

From Apollo Belvedere to George Bryan Brummell and Bimini Bon Boulash, co-curators Claire Wilcox and Rosalind McKever have embarked on the V&A’s first, and perhaps last, menswear retrospective. Set across three galleries – Undressed, Overdressed, and Redressed – the exhibition is a sprawling attempt to trace the ways in which clothing has refuted and restated staid notions of masculinity. To do this, Wilson and McKever skew chronology, housing the work of contemporary designers alongside historic artefacts, making blunt the parallels between past and present.

This is, at times, an engaging device. The relationship between classical sculptures and the beauty standards upheld by Calvin Klein campaigns, Jean-Paul Gaultier, and gender-affirming Spanx – which cinch the silhouette to Greco-Roman proportions – was elucidating. But as the exhibition snaked into its second and third act, this style of assemblage began to feel lean too heavily on comparisons to silhouette, fabrication, and form, while flattening the respective designers’ extraordinarily different contexts of production. Beyond their aesthetic similarities, the lamé, pussy-bowed jumpsuits of Harris Reed and a 1759 portrait of a British politician wearing a cerise cloak had very little in common, for example.

Backdropped by a swell of anti-trans rhetoric in the British media, the exhibition understood that men’s fashion is a profoundly political set of principles, so potent that others will try to oppress it. Nigerian designer Adebayo Oke-Lawal of Orange Culture, who lent a piece to the exhibition says, “where I’m from, we’re attacked and killed for talking about this, so it’s imperative to have these kinds of conversations.” With this in mind, an Alessandro Michele quote, stamped on the entrance of the show, seemed to set the agenda. “It seems necessary to suggest a desertion away from patriarchal uniforms. Deconstructing the idea of masculinity as it has been historically established”. But this messaging was thwarted by the sheer amount of ephemera on show. Two rooms were dedicated to the significance of colour and print, yet there was no real focus on sportswear, workwear, hipster or hypebeast culture, all of which have done more to shape masculine identity than 19th-century teapots.

Trite as it may sound, logo hoodies and branded trainers are just as worthy of a glass plinth in the V&A. The most disappointing omission, however, was the lack of hip-hop references, the proponents of which have done more to whittle away at the edges of gendered dress than pop stars like Harry Styles. A fleeting music video clip of A$AP Rocky’s Babushka Boi did little to telegraph the genre’s impact on fashion – these kinds of gaps punctured holes in Wilcox and McKever’s mapping of masculinity. A section on Anglomania included a Burberry puffer jacket by Riccardo Tisci, but it was deserving of the same designer’s leather Givenchy kilts, which were worn by Kanye West and his contemporaries – “the kilt is an inherently gender-fluid piece,” as exhibitor Nicholas Daley explains of his own creation, “which has been deconstructed and reconstructed by subcultures throughout the years”. For those hoping to understand how and why men dress the way they do today – cis, trans-masc, nonbinary, or otherwise – Fashioning Masculinities does not provide the answers.

That being said, with limited space, access, and archives, the V&A has proven that menswear is just as much a site of experimentation as womenswear. And when so much of engaging with fashion is based on conjecture (ie; observed through a phone screen, with most garments never making it onto the shop floor, let alone a wardrobe) it was exhilarating to see so many cultural lodestones brought to life, from Marlene Dietrich’s 1930s suits to Gary Oldman’s cold-blooded turn at Prada’s Autumn/Winter 2012 show. A constant referencing to the past underscored the methodology of many young designers too, like Priya Ahluwalia, whose vibration-raising Joy tracksuit stood alongside ensembles by Martine Rose, Orange Culture, and Rahemur Rahman. “I’m always interested in looking at historical garments,” says Priya. “But I like to experiment with details, shapes, colour, and print. Men have been wearing practically the same clothes for 50 years, so you have to slowly push them with each piece.”

Illuminated by floor-to-ceiling video screens, the final room positioned Harry Styles’ US Vogue dress, Bimini Bon Boulash’s finale gown from Ru Paul’s Drag Race, and the tuxedo-skirt worn by Billy Porter to the Oscars as the next frontier of menswear. But fashion has forever been a space in which non-normative gender identities have been accepted, powered by subcultural figures, whose shape-shifting approach to dress gave onlookers a sense of freedom and agency in their own identity formation. (Leigh Bowery would have snarled at the sight of Porter’s red carpet looks.) The porosity between menswear and womenswear, as evidenced during Miu Miu’s latest A/W22 show, would have been a more interesting proposal, speaking to gender ambivalence rather than ambiguity.

For all its frustrations, Fashioning Masculinities is a good example of how gender fluidity has moved from the margins of activism to enter public consciousness. As menswear continues to develop and explore new terrains, new cultural tendencies will emerge, and while the spectre of effeminacy is no longer feared, the fetishisation of fluidity can prove a buttress to the binary more than it does a bulwark. And though Fashioning Masculinities is sweeping in its survey of gender, the opening of masculinity is clearly prodigious and that, perhaps more than ever, is something to be celebrated.

Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear is on at the V&A until 6 November 2022.