The visionary American artist’s practice extended beyond the canvas and into her sartorial identity, as a new exhibition about her clothes neatly proves

Georgia O’Keeffe was an important figure of modern American art throughout her career, yet one of the most remarkable things about her might be her extraordinary capacity to stay true to her unique vision throughout that time. She developed a strong formal vocabulary, both on and off the canvas, and as Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern, a new exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, shows us, her vision extended far past the studio walls. Born into a severe Victorian world, O’Keeffe turned to progressive ideals from an early age, aligning herself with the principles of the Arts and Crafts Movement. She was drawn to the idea that every object we choose to live with should reflect an individual and unified vision, and she very seldom deviated from hers.

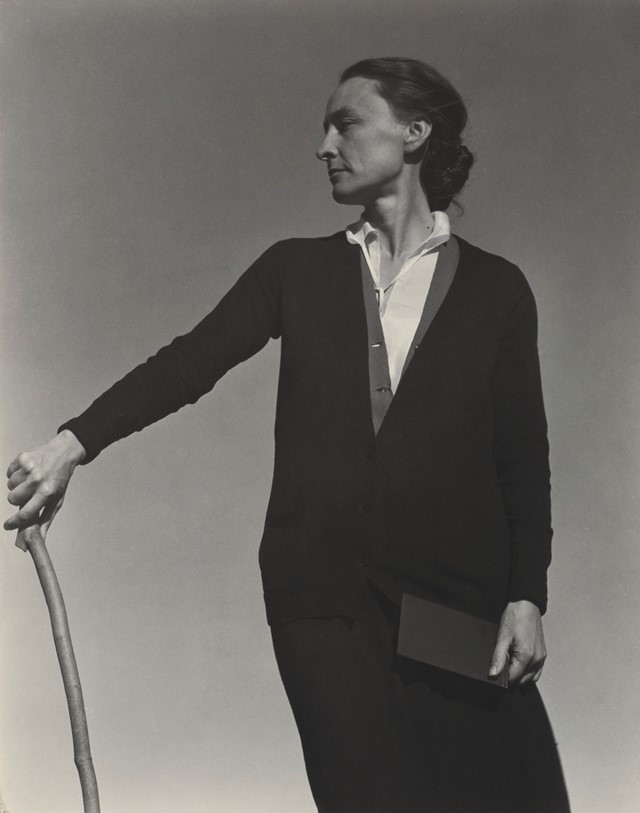

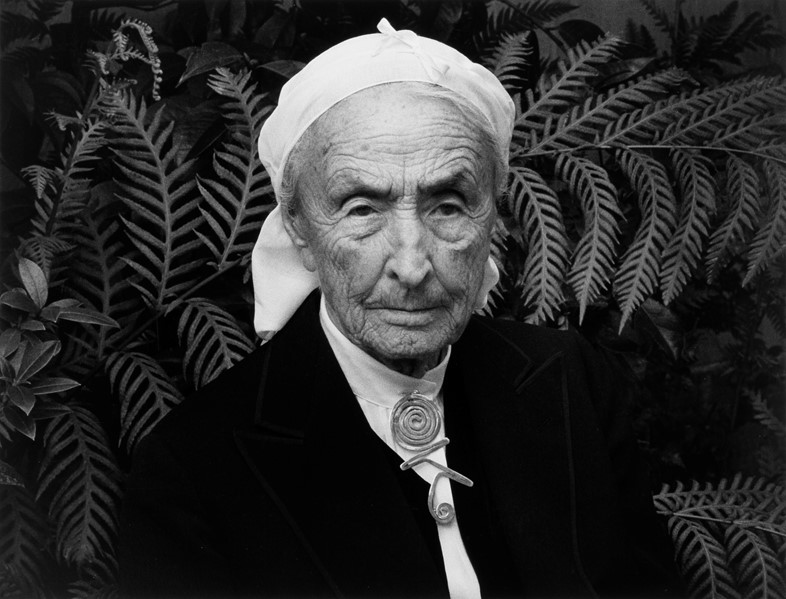

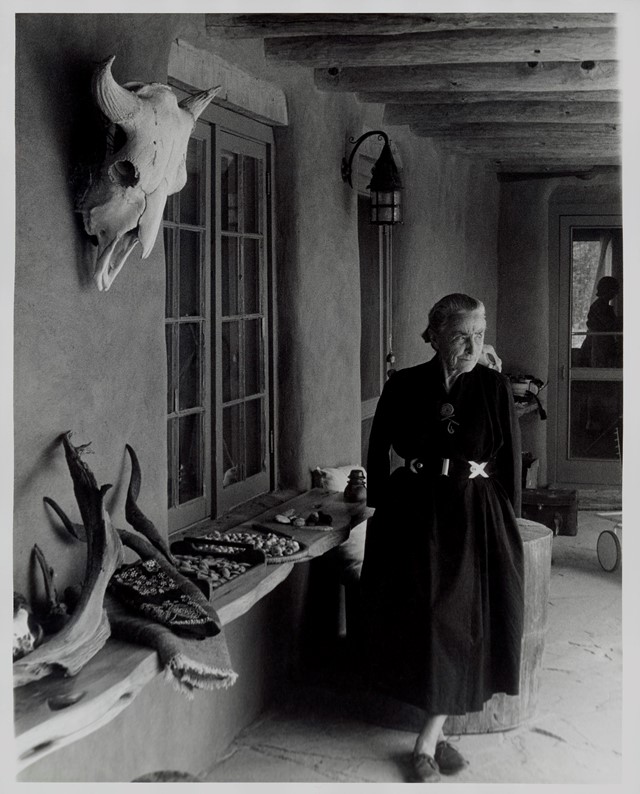

Key pieces of her wardrobe (which she meticulously took care of throughout her life, even keeping some early clothes she made as a child) will be on display alongside her paintings, drawings, and documentation of her residences – including the austere New York City apartment she shared with Alfred Stieglitz and her two homes in New Mexico. The many photographs that have been taken of O’Keeffe over the decades chart the evolution of her self-image but also draw attention to the ways in which both her character and style remained consistent throughout her life. On the occasion of the exhibition opening, we spoke to curator Wanda Corn about O’Keeffe’s precocious sense of self, her grave public persona, and her enduring mystique.

On how her independence informed her style...

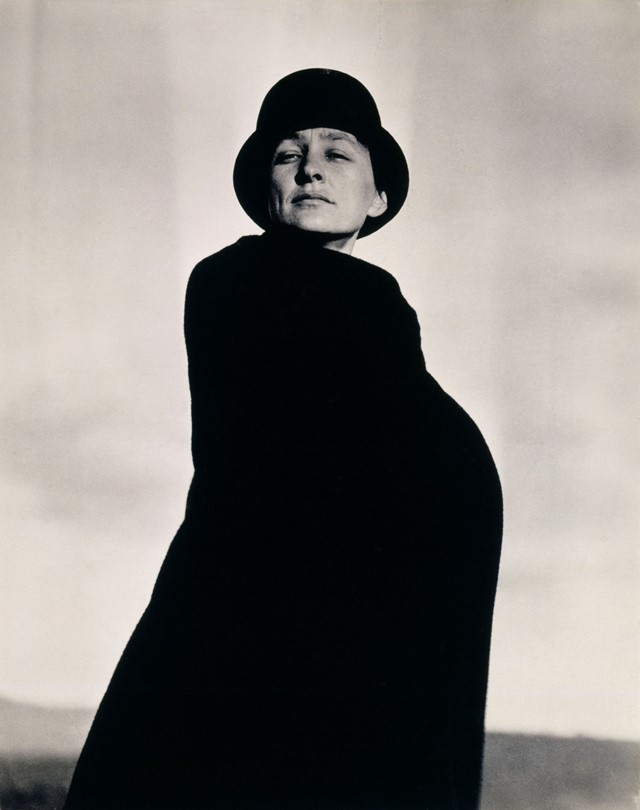

“[O’Keeffe] always liked to be independent of others, and not be a groupie; you can see that personality trait already in her childhood. In her high school yearbook she’s characterised as independent, without much care for traditional notions of femininity. A girl who would be different in habit, style and dress. A girl who doesn’t give a cent for men and boys still less. That character was just in her DNA. She grew up at the same time that women began having this notion of there being a new way of dressing. She never dramatically changed her style from X to Y, she was very consistent. She watched what was going on and then created her own version, always at the more radical end of the fashion world. She was part of the feminist movement in her youth, very early on. If she ever had corsets, she got rid of them and started wearing very full dresses. She started to limit herself to a palette of black and white – mostly black when she took photographs – and she was very thoughtful about how she could adapt the emerging reformed dress style to her own internal need to always look under-decorated, almost elementary, and to be practical and comfortable but still have a beautiful shape.”

On the influence of the New Mexico landscape…

“To my surprise, she had most of the elements of her New York wardrobe when she arrived from Texas. She made new pieces when she was with Stieglitz but she had already decided that black and white was her palette, that she was going to wear loose clothing with soft lines, that she liked monochromatic outfits – no figural patterns, and that she had an eye for really pure, beautiful materials – she liked wools, cottons and silks, organic fibres. She brought all that with her to New York.

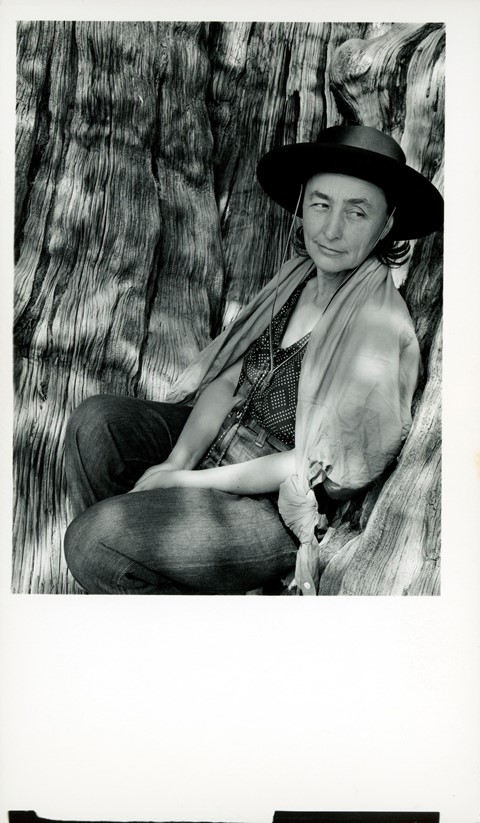

After Stieglitz died in 1946 she moved to New Mexico and changed to a more regional wardrobe. Place had a profound role on that transformation. She started wearing denim once she moved to the Southwest. She wore jeans and denim shirts with this beautiful white felt hat, like a gaucho hat. She also started using colour in her everyday dress. Particularly after WWII, black seemed rather gloomy and America went colour, women went colour, and so did she. She also bought four Marimekko dresses around 1950. And it was in New Mexico that she created the style of wrap dress that became a staple. Her favourite designer, if she had one, was Claire McCardell, and she created a wrap dress around 1950, and then other versions of it circulated. Georgia bought her first wrap dress from Nieman Marcus and she realised it was her favourite way of dressing in the Southwest. She never wore them when she travelled to cities, but she did wear them in New Mexico. And the colours that she was drawn to were very tied to the landscape of New Mexico – beautiful yellows, blues, pinks.”

On her evolving relationships with photographers…

“When she started to be photographed by Alfred Stieglitz – he was the first to make art photographs and portraits of her – she did not have any experience modeling. She had modeled for painters, but she hadn’t been a photographer’s model before. It’s clear that he had a lot of say – he often used extreme poses that she would not have fallen into naturally, so it was apparent that she was being directed. In the early years, she learned how to be a model for him and then in the later years that he was photographing her, she knew what pleased him. My sense is that after being very much his subject, she begins to work with Stieglitz. Later, when he dies and all these other photographers come rushing in to fill the vacuum, she still takes directions but she also made suggestions. Her relationship to photographers evolved into a partnership.”

On mystique…

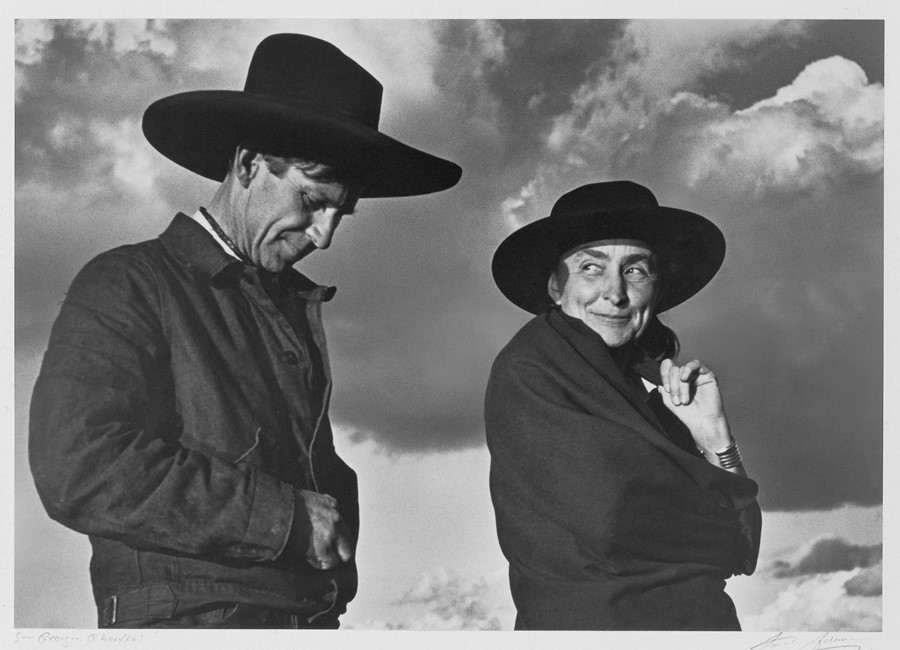

“We have lots of evidence of her telling photographers “Don’t photograph me smiling” or “I won’t smile”. I think that grave, mystical look you often see in the photographs was something she worked on with Stieglitz, but it really became one of her ground rules. But then there were some photographers in the new, younger generations who were able to show a side of her that was softer, a little mischievous, even flirtatious, occasionally. Ansel Adams made photographs like that. She could be very informal – especially if she liked a photographer and if she was familiar with them. But those are not the photographs that become the iconic ones. That’s the point, I think. The photographs that show her as the great saintly presence on the desert – those are the ones with the mystique that is commonly thought to be her public persona.”

On iconicity…

“She never saw herself as a fashion icon. We made her into that, but I don’t believe that she had any desire to become known for instigating a particular fashion or popularising a particular fashion – I don’t think she was interested in that part of the fashion industry at all. If anything, she wanted to do things her way – because they looked like her and made her feel good. And she liked it because it made her look a little differently from other women at that time, she liked the way she could get an individuality of the body by using clothes, but she always insisted that those clothes also had to be comfortable, unornamented, and, as I tell many people who think she was bohemian – I wouldn’t call her that at all – bohemians like to dress counterculture, to do things as outrageous and unexpected and experimental as possible. That wasn’t her mode at all. Her mode was to look around closely at what women were wearing at the time because she never wanted to be contrary to fashion, she just wanted to be a more minimalist, severe version of anything that was fashionable at the time. In that way I would say she’s at the edge of fashion, not in the middle of it.

I don’t know what she would think of this show, frankly. I don’t think she would be upset, but she’d think it curious that anybody would be interested in her clothes at the same time that they’re interested in her art. I think she might be flattered too in a way. She had this notion that what she did was always ‘fill space in a beautiful way’, as she put it, and I think she would appreciate that someone noticed that quality in all aspects of her life, not just in the studio.”

Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern runs from March 3 – July 23, 2017, at The Brooklyn Museum. The corresponding book is out now, published by Prestel.