In the stucco and mirror salons of Balenciaga’s headquarters on rue du Cherche-Midi, the shaven-headed Demna Gvasalia looks out of place. He’s wrapped in a giant black blanket of a coat and a heavily-hooded sweatshirt (the hood is down), at a modern round table flanked by leather chairs. On a mantelpiece sits a black and white striped ceramic vase that may or may not be by Ettore Sottsass. Along with the table and chairs, it looks left over from the lauded 15-year tenure of Nicolas Ghesquière, whose modernist reinterpretations of Balenciaga’s legacy and silhouettes (cocoon-backed coats and dresses coated in latex, plated in metal or in floral-smothered neoprenes) left Balenciaga in a winter of discontent upon his departure in 2012. In an adjacent room, the final collection of Gvasalia’s predecessor Alexander Wang flutters prettily, but inconsequentially. It’s November 2015. In four months’ time, Gvasalia’s debut collection is due.

Gvasalia isn’t used to salons. At least, so the story goes. He’s the head of the Vetements label, a Paris-based collective that has hitherto shown in gay sex clubs and Chinese restaurants, gaining much traction and attention. Its showrooms were in an old concrete furniture showroom near the Gare du Nord, and its peripatetic studio spaces have shifted around the enclaves of the down-at-heel 10th arrondissement. Vetements propelled Gvasalia to Balenciaga – it was short-listed for the LVMH Prize, and showed a critically lauded Spring/Summer 2016 collection days before Gvasalia’s appointment was announced. That collection was its fourth – Vetements has existed for just over two years.

The proposition of the two labels, on paper, seems diametrically opposed. Vetements is obsessed with street culture, with the trashy, the bad taste. It makes clothes from polyester lurex, from fake leather, and the kind of slithery, clingy velour previously utilised for Juicy Couture tracksuits, before they fell so decidedly out of fashion. Balenciaga, by contrast, is the home of thoroughbred elegance; a name synonymous with midcentury couture, revered within the lifetime of the house’s founder, Cristóbal Balenciaga, and near-deified since his death in 1972. Christian Dior dubbed him “the master of us all”; Madeleine Vionnet reputedly wore the robe he made her until she died. Balenciaga’s favourite fabric was gazar, a textile invented for him by the Swiss fabric house of Abraham, with the sheen of silk and the holding power roughly equivalent to corrugated cardboard. It allowed Balenciaga to create the sculpted shapes he adored, and which became synonymous with his name. The only similarity between the two is a love of unconventional fit: Balenciaga invented the semi-fitted suit; Vetements reinvented the baggy sweatshirt. Even then, they’re unlikely bedfellows. “Grand” is the word for Balenciaga. Vetements is more “grubby”.

“For me, it wasn’t so much about clothes, to be honest. It was more about finding out about Cristóbal – his method of designing, of making clothes.” Demna Gvasalia

How to ally Gvasalia with Balenciaga, bar a vague half-rhyme and a love of the oversized? Gvasalia first did his research: watching documentaries, reading, spending a day early in his tenure immersed in the archive where Cristóbal Balenciaga’s own garments are encased in white calico and those of his successors in black (Mark Borthwick photographed the pre-Fall 2016 Balenciaga lookbook there). “But for me, it wasn’t so much about clothes, to be honest,” says Gvasalia, the heresy echoing around the salon. “It was more about finding out about Cristóbal – his method of designing, of making clothes. This method was, for me, the reference, starting the collection, rather than a certain garment or known shapes.”

Gvasalia is 35, was born in Georgia in the former Soviet Union, raised partly in Germany and educated in Antwerp. He originally studied economics, under the parental yoke, and pursued a career in banking before breaking free and travelling to Belgium to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp. “I had no money,” he says now. “When I had to buy five metres of cotton, I knew that that day, there probably wasn’t going to be dinner. But that was also the fun part, because we managed to make things out of nothing.” After graduating in 2006, Gvasalia worked for Maison Martin Margiela, in the years following the founder’s departure, from 2009 to 2013. He then worked for a year at Louis Vuitton, under Marc Jacobs and former Balenciaga designer Nicolas Ghesquière. Vetements was established with a pair of friends, also working at other houses. It was financed with the money Gvasalia earned from his Vuitton gig – hence he became titular head. The nascent company – named “Vetements” to hide the moonlighting status of the two other designers – showed its first collection on a rail in the Marais for the Autumn/Winter 2014 season.

“The attraction of the house was, definitely, the idea of couture. The idea of a certain noble elegance, and the idea of beauty that he had. That, for me, is something that I would never be able to do with my own brand.” Demna Gvasalia

Many question how Gvasalia could shift from Vetements’ apparently vehement anti-fashion stance into a company like Balenciaga. Part of the Kering conglomerate, Balenciaga’s turnover stands at about 350 million Euros. The brand has around 100 freestanding stores, and a voracious e-commerce business delivering to some 95 countries across the world. Yet Vetements was not born out of a crusade against corporate fashion, says Gvasalia, but frustration. “Basically we [Gvasalia and his fellow Vetements founders] had these frustrated, horrible talks about fashion, hating everything, hating our jobs even though we had good salaries. We could have a nice lifestyle, but boring.” And Balenciaga offers something different to other houses – and something different to Vetements, too. “The attraction of the house was, definitely, the idea of couture,” says Gvasalia, softly and unexpectedly. “The idea of a certain noble elegance, and the idea of beauty that he had. That, for me, is something that I would never be able to do with my own brand. Aesthetically, or in any way. The word elegant doesn’t work there, it’s out of that vocabulary. For me, here, it’s that. And I was really very curious and hungry to discover that. I felt like I had a sensibility towards that, but I could never explore it.” Balenciaga doesn’t create couture – only about a dozen houses do, most of those employing corner-cutting to make the exercise profitable or at least not as prohibitively expensive. But Gvasalia does have an atelier of skilled craftspeople, to help engineer his ideas – which he insists aren’t retro (a word he spits out). “Originally it was, ‘Let’s not do a bomber here – because we have a bomber there’,” Gvasalia says, of Balenciaga and Vetements respectively.

It’s now a couple of days later, outside the salon and close to Vetements' base in the 10th arrondissement. He’s wearing a hoodie in green sweatshirting that’s faded to a mouldy khaki. A long-sleeved T-shirt from the Spring/Summer 2016 Vetements collection pokes out from beneath; on each forearm, lurid, horrormovie scarlet typography scrawls out the words “COMING SOON”, as if advertising the yet-to-be-designed Balenciaga collection. “But how do you do that differently?” he continues, as I look at that instantly indentifiable Vetements outfit and also wonder how. “I think that’s where it’s the hardest, but the most exciting too. I think I’m starting to find those instruments at Balenciaga as well, which makes it easier. It’s a beauty aspect; at Vetements it’s always very much like, ‘It’s ugly, that’s why we like it’,” Gvasalia laughs. “There it doesn’t exist at all. That I like a lot.”

“At Vetements it’s always very much like, ‘It’s ugly, that’s why we like it’. [At Balenciaga] it doesn’t exist at all.” Demna Gvasalia

I meet Demna Gvasalia again, months later, a few days before his Balenciaga show. Vetements has already shown its offering for Autumn/Winter 2016, among the pews of the American Cathedral in Paris – a symbolic stone’s throw from 10 Avenue George V, where Balenciaga’s couture house was originally located (that of Hubert de Givenchy, Cristóbal’s protégé, is still across the road). Back on the Left Bank, the Balenciaga studio isn’t a salon, but rather a grey carpeted, boxlike office filled with racks of clothes, across the road from our original rendezvous. Balenciaga’s operations have expanded to a scattered collection of buildings around a showroom on rue Cassette, where Nicolas Ghesquière frequently showed his collections. (Two months after Gvasalia’s debut, they will be pulled under a single roof, of the former Hôpital Laennec, named after the inventor of the stethoscope.)

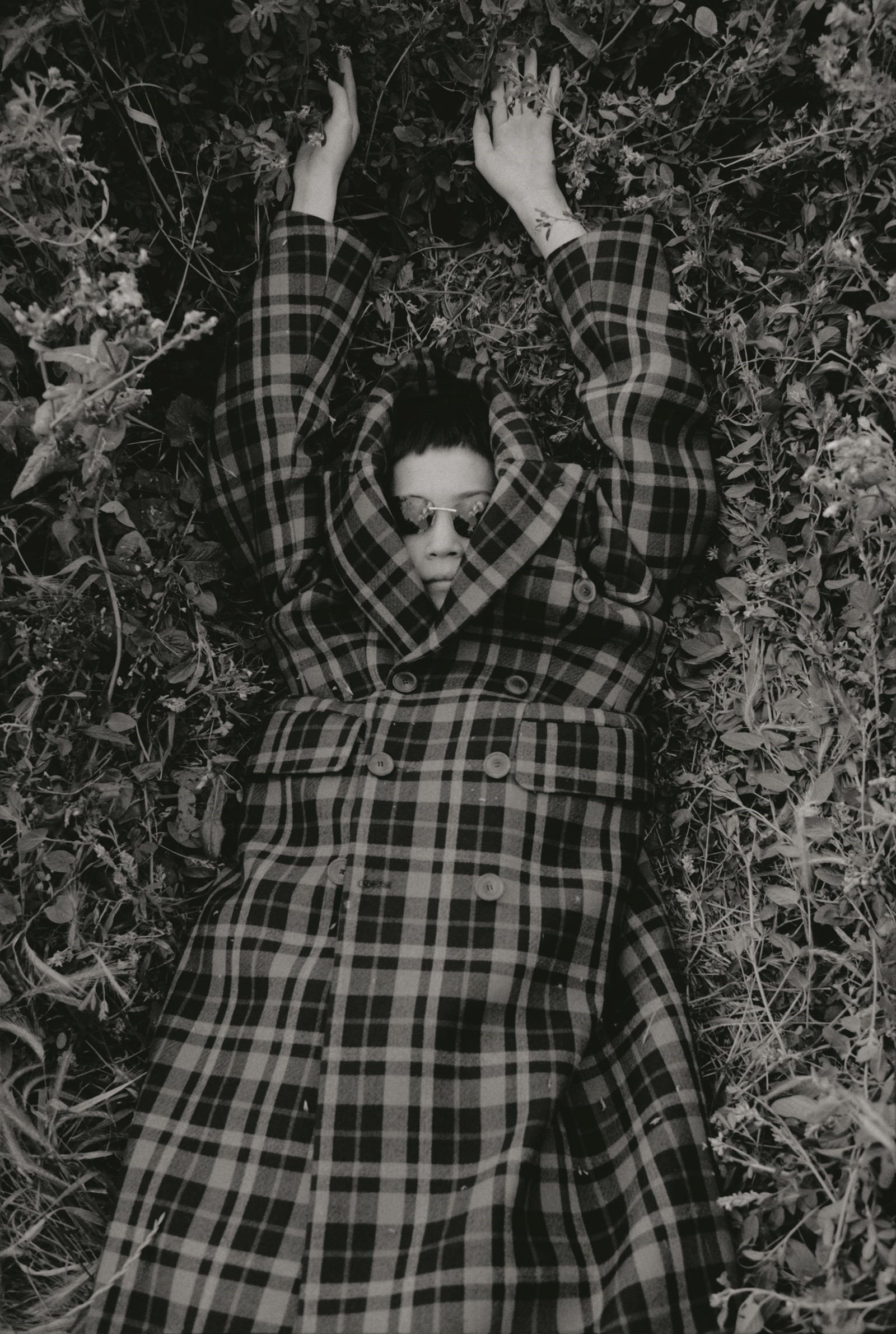

Gvasalia seems more at home in the boxy studio, which is ugly, Vetements-style, for want of a better Balenciaga-ism. Alongside him in the studio, Lotta Volkova, the Vladivostok-born stylist for Vetements and Balenciaga, and the only member of the team to accompany Gvasalia in the move, dresses models in garments, frequently trying them on herself with glee. At the back of the studio, a board is pinned with imagery – mostly 50s couture mannequins, dourfaced and holding numbers. There are also a clutch of photographs of preschoolers in vastly oversized coats by the Norwegian outerwear manufacturer Helly Hansen. Their laughing faces sit alongside Irving Penn’s icily perfect image of his wife, Lisa Fonssagrives, veiled above a cocoa-coloured Balenciaga taffeta dress from 1950.

“I read this story about him draping fabric on a dummy of an old client,” says Gvasalia, “who had this posture...” He hunches over, arching his back into a hump. “I remember Givenchy saying he was there and he saw it happen – this old woman suddenly became straight. He changed the posture and the attitude by this architecture of draping, how he worked the volumes. For me, that was really the most important part. The source of inspiration. How do we do that today?” Gvasalia talks a lot about attitudes when speaking about his Balenciaga. What he’s interested in, he says, is the notion of transforming the body through the clothes that dress it, of the garments helping to redefine the form inside. Cristóbal Balenciaga did a lot of that – his cut-away collars elongated necks, his cropped sleeves attenuated limbs. “He wanted the woman to be better than she was, with everything he did,” emphasises Gvasalia. The architecture of Balenciaga was aimed, ultimately, to flatter a woman.

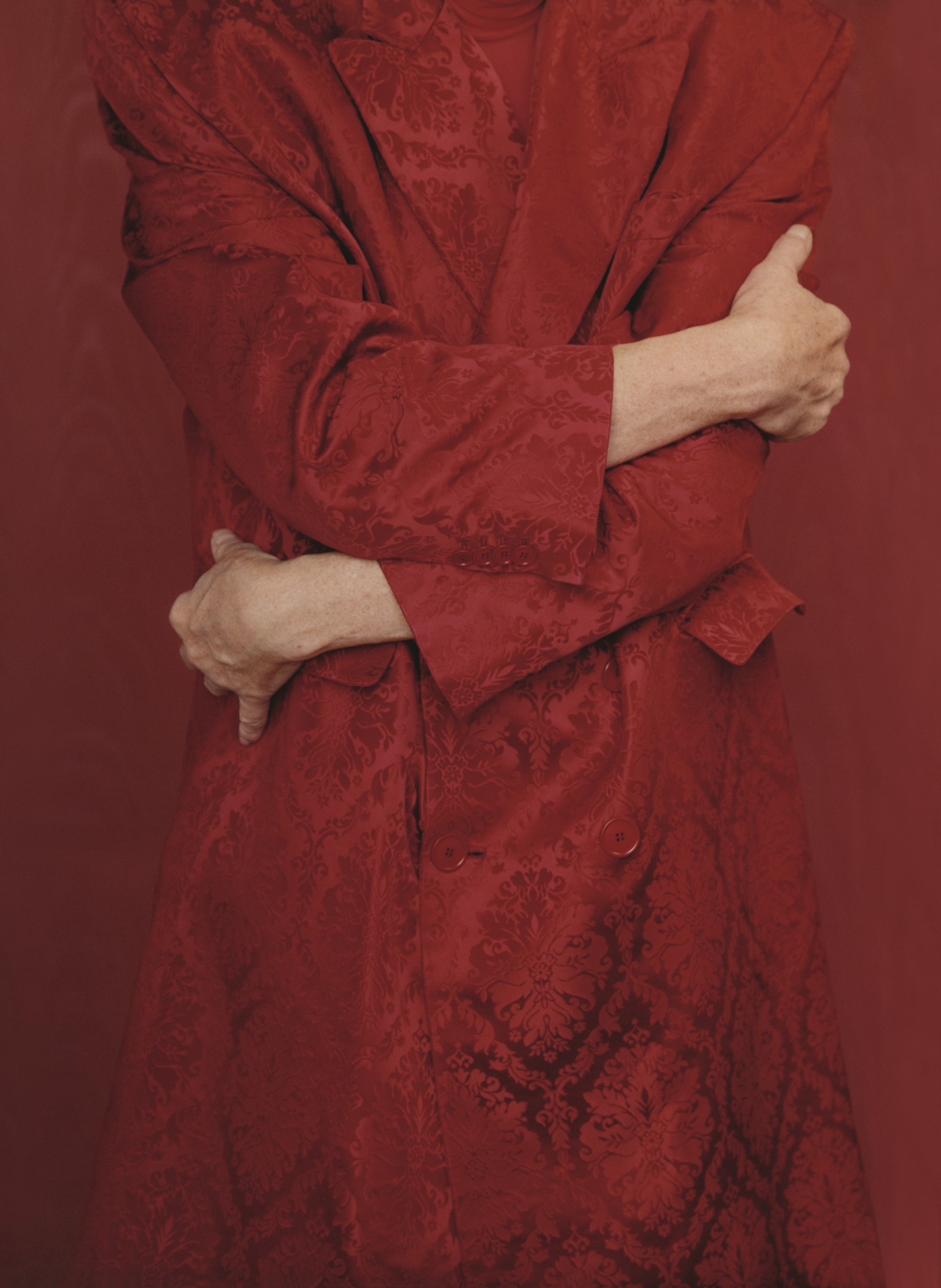

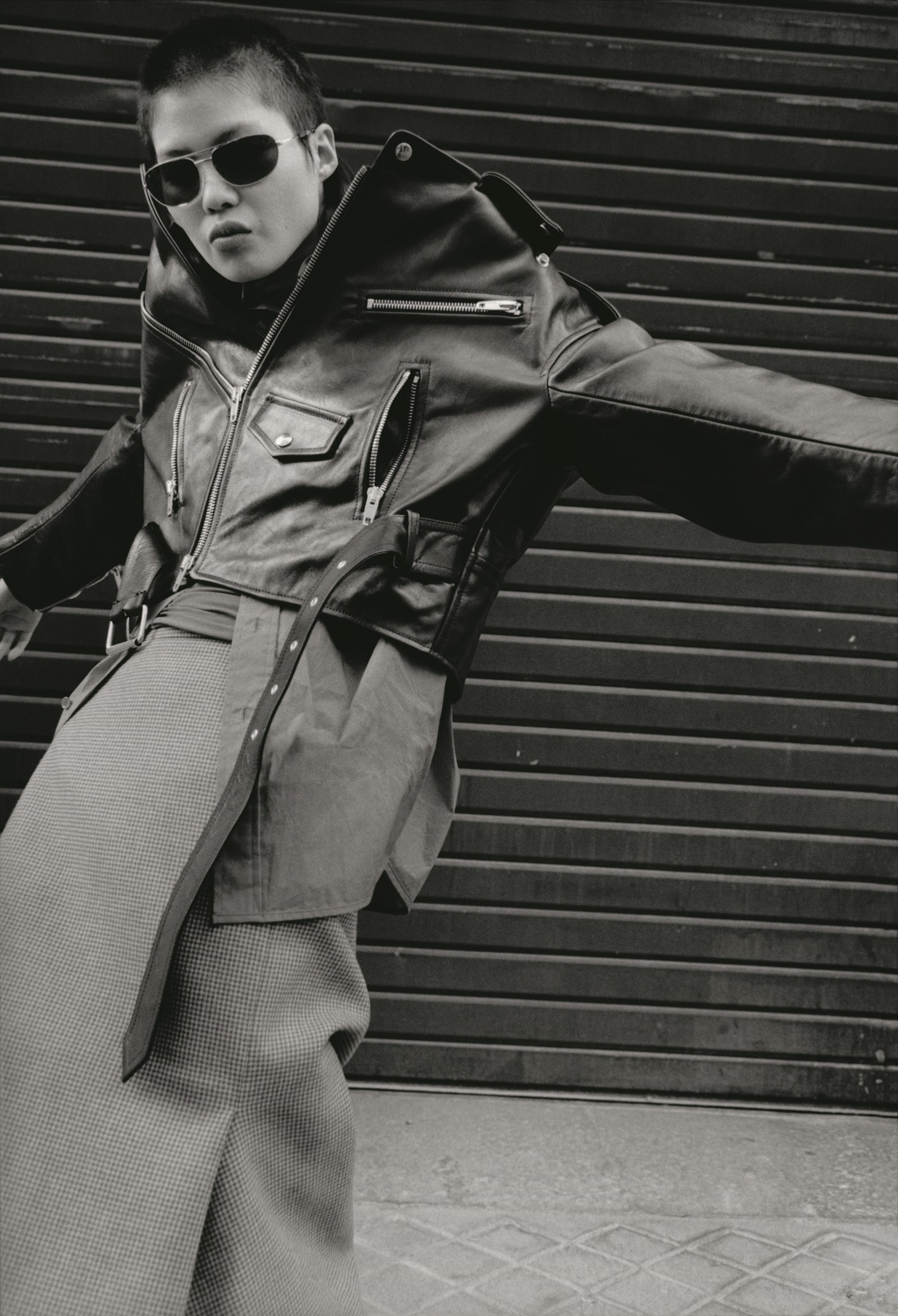

A few days later and that is the starting point for Gvasalia’s first exploration of Balenciaga, founded in the method rather than, perhaps, the archetypal garments you’d automatically associate with, say, Mona von Bismarck (a socialite aristocrat who had every garment in her wardrobe – including her gardening clothes – made by Balenciaga, and who withdrew from society for three days following his retirement in 1968). Gvasalia too is obsessed with the notion of designing a wardrobe: Mona would have baulked at his though, at a downpuffed jacket, an anorak, a billowing tentdress in jarring florals, or a beaten-up, 70s-style leather trench coat. Even when he went conventional and offered embroidered evening dresses, with custom fabrics created by Schlaepfer, they mimicked cheap evening gowns that Gvasalia and his team had found in discount Paris stores, themselves alluding to the idea of couture stereotypes.

But there is a similarity in attitude between Gvasalia and Balenciaga. A connection in approach – a parka cut to fall off the shoulders, intentionally, and frame the décolletage like a grand opera coat; suits with jutting basques emphasising a handspan waist; and a series of garments seamed into a distinct curve, imitating the concave-torso stance of Fonssagrives et al in the imagery that still cements Balenciaga’s identity in contemporary consciousness. “Clothing cannot be static,” comments Gvasalia. Then, he laughs. “Unless you’re dead!”

Gvasalia is talking, specifically, about clothes actually shifting around on the body – but ideologically, the phrase is also true. Balenciaga cannot be mired in its own past, for Cristóbal Balenciaga himself never was. What made Gvasalia’s debut so compelling was the fusion of tradition with innovation, of a new aesthetic with an old approach. A rethinking of the Balenciaga legacy, beyond the tired, trite clichés of architectural volume and haute couture hauteur. It was, however, distinctly Balenciaga – a link that the first Mark Borthwick look-book, shot in the archives, visibly forged. “You’re not coming to a blank page. There are certain recipes you need to consider,” comments Gvasalia the next time we meet. “Every time I see a piece, during a fitting, or if there’s an idea, it’s like, is it Balenciaga? Not, Does it remind you of Balenciaga? Can it stand? Do you understand why it is Balenciaga? It can be jogging pants, but why?"

He’s speaking to me well after his debut, from his new office in the Hôpital Laennec. It’s now April and after that first show, and the overwhelming reaction (varying from glowing to incandescent in praise), it’s easier to make a case for Gvasalia and Monsieur Balenciaga sharing an approach without seeming like a Vetements evangelist. Although there are many of those, the symbolism of Paris fashion’s oft-perceived great white hope showing in a church was lost on few. Like Balenciaga, Gvasalia can sketch, but doesn’t. “It’s so two-dimensional,” he says, deadpan, before reasoning that, with the current schedule of work, it’s also simply not possible. Gvasalia has a point – he’s already knee-deep in preparations for the next Vetements show (a deadline jumped forward to July, as part of the Haute Couture season, rather than the usual October), as well as his first Balenciaga pre-collection and the house’s first ever menswear catwalk show in June.

“I prefer working with either existing or recycled garments... I believe you have to destroy a garment to make a new one.” Demna Gvasalia

Incidentally, Balenciaga did make clothes for men – for himself. Gvasalia and his team are basing the collection around that notion. Behind me hang a few pieces of the forthcoming Balenciaga Resort collection: striped poplin shirting, a toile of a nylon windcheater with a dip cut into the back of the neckline – a reflection of the shoulder-swathing parkas from Autumn/Winter, Gvasalia says. The windcheater is some cheap, shop-bought piece, but every other seam has been ripped open, and a slab of calico inserted into the nape. It’s been re-engineered. “We started to cut existing pieces, and twist the shapes, to get to this,” says Gvasalia, tweaking the jacket. “This is my approach, to working with clothes. For me, it’s sculpture.” There are shades of Cristóbal there, for sure. “I prefer working with either existing or recycled garments,” he continues, “to be able to cut them, destroy them, make new proportions. I believe you have to destroy a garment to make a new one.”

I wonder if, perhaps, you have to destroy a fashion house to make a new one; if Gvasalia has to tear down our preconceptions about Balenciaga’s refined, aristocratic but formaldehyde-preserved mid-century pedigree in order to progress? If it’s necessary for him to tear Balenciaga apart at the seams, like that nylon windcheater, to create something new? But the house is already unrecognisable from what Cristóbal Balenciaga created – a couturier who refused to compromise or commercialise, who bowed out rather than kowtow to the burgeoning world of ready-to-wear, declaring he would not prostitute his art.

Downstairs at the Hôpital Laennec, in a giant cruciform atrium, the personal orders of Balenciaga staff have begun to arrive, black polythene bags taped up and stacked three-deep and several hundred metres long. Gvasalia seems thrilled when he sees them – he says he really wants people at Balenciaga to wear the clothes. First and foremost, above all else. “For me it was really this challenge,” reasons Gvasalia, plainly. “I want Balenciaga to sell clothes, to dress women.” It sounds like something of a revolution at a house known, in its earliest days, for proposing women as walking abstract columns of taffeta or globulous bows of satin. In its latter incarnation, the focus was on accessories and catwalk impression, rather than translating those statements onto people’s backs. But fundamentally, what Gvasalia wants to do is to return Balenciaga to its core values – no party tricks, no catwalk theatrics. Pure clothing, true and simple. A real wardrobe. “That’s what he did,” says Gvasalia, earnestly. And you really want to believe what he believes.

Hair Gary Gill for Wella Professionals using EIMI; Make-up: Inge Grognard at Jed Root using MAC Cosmetics; Models Manami Kinoshita, Patricia Lu and Nick Zedd; Photographic assistants Rachel Lamb and Mourad Boudrahem; Styling assistants Elena Cavagnara and Margaux Dague; Hair assistants Tom Wright and Mikio Aizawa; Make-up assistant Josephine Bouchereau; Post-production Upper Studio; Production Art Partner; Onset Production Shape Production; Special thanks to Mires Locations.

This article was originally published in AnOther Magazine A/W16.