While Alexander McQueen moved many to tears with his extraordinary London shows – shows that included Bellmer La Poupee, Joan and The Overlook – he himself would regularly claim that he wasn’t sure what all the fuss was about. No. 13, he said, was "the only one that actually made me cry". It was staged, as all the collections of that period were, at Gatliff Warehouse, an unused former bus depot in Victoria, for the spring/summer 1999 season. There was no celebrity front row. Victoria Beckham famously asked to be invited to No. 13 and received a polite thanks but no thanks: her presence would detract from the main event. McQueen and his team worked too hard on their shows for the focus to be on any guest, the story goes. No. 13, in particular, was sensitive as far as subject matter was concerned. And so McQueen’s friends and the world’s most important buyers and press walked in to find a ground-level set made out of nothing more grand than unvarnished floorboards with a lowered, lit ceiling suspended above it and all quietly took their seats.

The Show

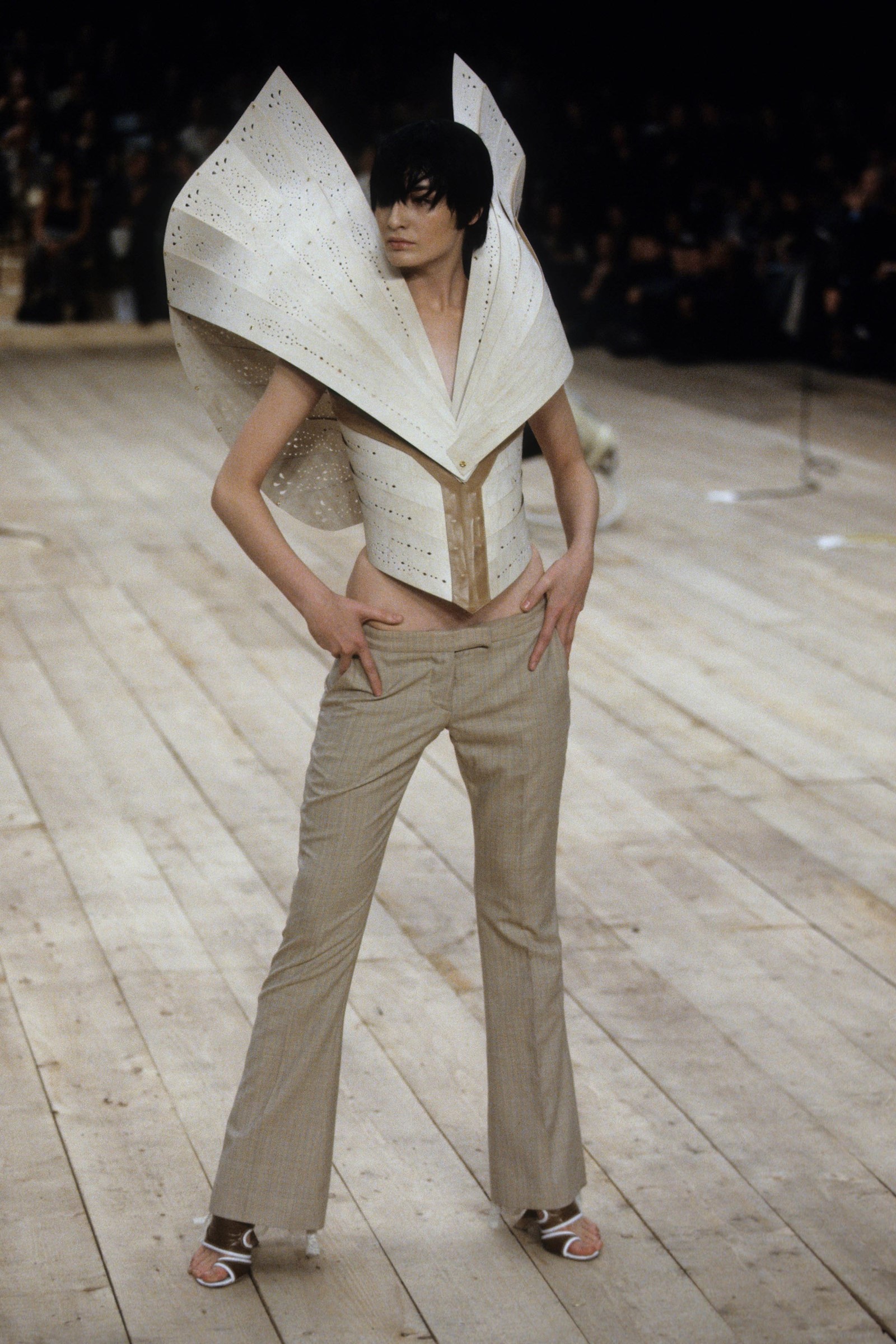

No. 13 – named as such because it was the designer’s 13th show – was McQueen’s most open tribute to the Arts and Crafts Movement, the main protagonists of which interested him throughout his career. Designs were constructed in predominantly natural tones including tan, beige and ivory and used everything from raffia, for intricate bodices and fringed skirts, to balsa-wood, cut into strips and punched then manipulated into delicate fan-like designs, and from tiered, ruffled lace to leather. The latter formed asymmetric belts, corsets and moulded harnessing, often crudely stitched, and inspired by the workshops of Queen Mary’s Hospital in Roehampton, which pioneered prosthetics for those injured during World War I. These invested a gentle and romantic vision with the typically tough, even sinister undertones that characterised McQueen’s greatest work. Shoes, too, had a vaguely orthopaedic look about them. And McQueen had good reason for that.

The People

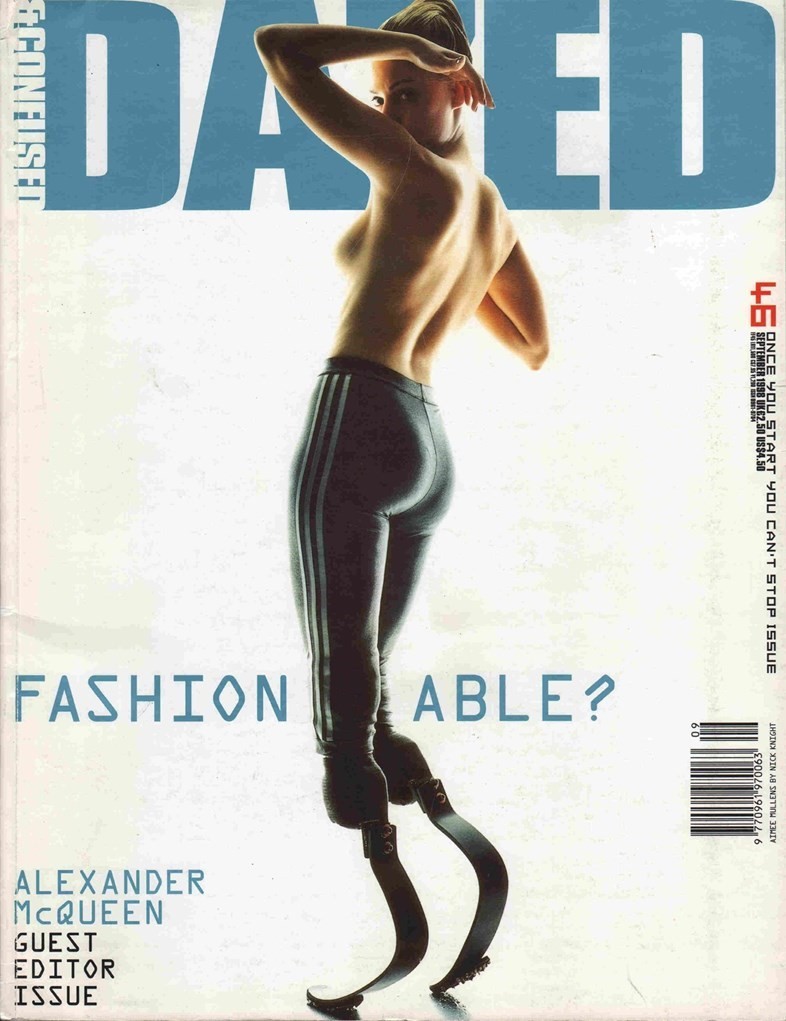

McQueen famously guest-edited the September 1998 issue of Dazed & Confused magazine which came out only days before No. 13 was staged and put Paralympic champion Aimee Mullins on the cover, shot by Nick Knight and styled by his then creative director, Katy England. Mullins was wearing metal ‘sprinting’ legs, the shape of which was based on a cheetah’s foot. Inside, a series of other subjects, all with physical disabilities, were also photographed in designs by McQueen himself, but also Hussein Chalayan, Roland Mouret, Owen Gaster, Philip Treacy and Comme des Garçons. Mullins also opened No. 13, this time in a pair of cherry wood prosthetic legs hand-carved to a design dictated by McQueen that whispered of the work of the Dutch-British sculptor and wood-carver, Grinling Gibbons, another recurrent reference in his work. In an interview for The Guardian covering both projects, Mullins told me that she was keen to be involved in the project because it was her ‘mission’ to challenge prevailing attitudes towards beauty. "I want to be seen as beautiful because of my disability, not in spite of it," she said. "People keep asking me: 'why do you want to get into this world that’s so bitchy and so much about physical perfection?' That’s why. That’s why I want to do it," she continued.

In the end, perhaps the most remarkable thing about her appearance on the catwalk was that only very few there knew that Mullins’ legs had been amputated from the knee down following an accident as a child. More than one in attendance went so far as to ask immediately afterwards if they could borrow her ‘boots’. And perhaps with that both her mission, and indeed McQueen’s own, had come some way towards being accomplished. "I’m not doing this to save the world or anything," he, for his part, said, "I suppose the idea is to show that beauty comes from within. You look at all the mainstream magazines, from GQ to Company to Vogue, and it’s all about the beautiful people, all of the time. I wouldn’t swap these people I’ve been working with for a supermodel. They’d got so much dignity and there’s not a lot of dignity in high fashion. I think they’re all really beautiful. I just wanted them to be treated like everyone else."

"I wouldn’t swap these people I’ve been working with for a supermodel. They’d got so much dignity and there’s not a lot of dignity in high fashion." Alexander McQueen

The Impact

It’s not news that London Fashion Week in the mid- to late-90s was home to fashion shows more akin to performance art than any traditional runway presentation. This was the heyday of Brit Art, Brit Pop and Britannia, apparently, was cool. McQueen’s shows were every bit as impactful as Oasis’ Definitely Maybe or Sensation at the Royal Academy, No. 13 perhaps most of all. There were several set pieces in the show which, incidentally, lasted over 20 minutes, which is unprecedented by today’s standards. The first two of these featured models spinning on circular disks at the four corners of the stage like precious music-box dolls dressed in gauzy silks or metal mesh that sparkled in the light. Above all, though, No. 13 will be remembered for its finale, featuring Shalom Harlow, a former ballerina, dancing on a fifth, centrally placed disk, between two metal robots hired from a car manufacturing plant. Their interaction began gently before the level of menace increased and the model’s pure white cotton trapeze dress was sprayed black and yellow as she turned.

This moment has been analysed extensively: some said Harlow was McQueen’s dying swan (he was, after all, obsessed with birds), others saw it as a thinly veiled reference to sexual climax (male). In fact, McQueen later said he had been inspired by artist Rebecca Horn’s 1991 installation, High Moon, for which two guns shot blood red paint at one another. On the hub launched to accompany the Savage Beauty exhibition that opened at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York a little over a year after Alexander McQueen died, Harlow said: "I walked right up to it and stood on top of this circular platform and as soon as I gained my footing the circular platform started a slow, steady rotation. It was almost like the mechanical robots were stretching and moving their parts after an extended period of slumber. And as they sort of gained consciousness they recognised that there was another presence among them and that was myself. At some point, the curiosity switched and it became slightly more aggressive and frenetic and engaged on their part. And an agenda became solidified somehow. And my relationship with them shifted at that moment because I started to lose control over my own experience and they were taking over. So they began to spray and paint and create the futuristic design on this very simple dress. And when they were finished, they sort of receded and I walked, almost staggered, up to the audience and splayed myself in front of them with complete abandon and surrender."