AnOther speaks to Paul Smith, Margaret Howell, and Solange Azagury-Partridge: three British brands for whom keeping shop in the right way is of paramount importance

French revolutionary Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac was recorded saying in 1794 that Britain was "a nation of shopkeepers" but, not so long ago, the demise of bricks-and-mortar retail seemed to be writ large. Online retail offered convenience for consumers, low overheads for brands and a far more efficient management of stock, with all goods in one warehouse rather than being scattered across shops. Global audiences could be reached without hefty rents, and cautionary tales about over-expansion of physical stores abounded, having played a significant role in the fall of mega brands like Quiksilver and Billabong. However, in an interview with management consultants McKinsey & Company, Devin Wenig, president and CEO of eBay explained that “the death of the store” had been greatly exaggerated, and that now, on and offline retail, in fact, have a complementary relationship.

As buying branded goods in and of themselves becomes less important, with sales of logo-ed luxury dipping and the ‘experience economy’ on the ascendent, numerous studies show that shops are places that designers can cultivate a tactile, meaningful, experiential relationship with their customers. They can employ like-minded people who appreciate their design ethos to work within them, and create a space that relates in a meaningful way to the objects they produce. A customer who browses in-store will often buy online, and the sale will be prompted by the memory of that physical, curated context, a conversation with a sales assistant, and the opportunity to try something on.

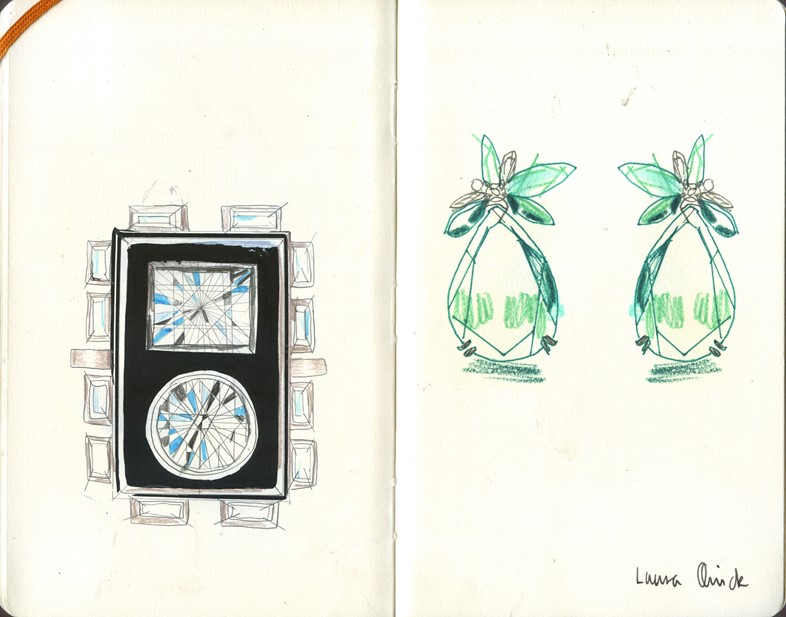

Of course, the shop has played a pivotal role in the success of several of Britain’s most successful global brands, notably Paul Smith and Margaret Howell, both of whom have substantial retail networks, particularly in Japan, where Smith has over 400 stores, and Howell around 100, as well as shops that helped to establish their brand DNA in London. Solange Azagury-Partridge, the highly influential luxury jeweller whose distinctive, playful work anticipated the likes of Delfina Delettrez, recently moved her London shop to a more intimate space in west London, realising that there was a disconnect between the multi-floored retail space she had in Mayfair, and the intimacy she wanted to cultivate for clients buying her jewellery. Here we speak to the three brands, to find and how and why they translate their design ethos into physical retail spaces.

Margaret Howell

For Margaret Howell, the presentation of other British-designed-and-made objects, alongside her clothing was a deciding factor in the move to the glorious, expansive shop on Wigmore Street, designed with Will Russell from Pentagram, in 2002. "We were finding the smaller shops frustrating, because one was wanting to put household goods, for want of a better word, alongside the clothing, so we looked for a bigger shop, but this one was enormous," Howell remembered. "But, because of the configuration of the whole space, we were able to bring the whole company here – admin, design and retail, and that was really perfect for us, because it felt like the complete workshop. It is so good to have design and retail close together, and to get that immediate feedback from retail staff," she continued.

"At the time, the company had grown to the extent that my role was design director, and I been designing for 30 years and was wanting more stimulus myself in the design area. I thought some of our British designers are undersung – or were – and I had already been collecting Ercol and I suddenly found it quite apt for today’s living, so I thought, "well we have the space’ and so I put the furniture in. One was collecting Robert Welch through charity shops and things too, and that is how it developed – putting in one’s own choice of things, and because it’s one’s own design values that run through both, they compliment each other – things are well made, fairly practical, British."

Paul Smith

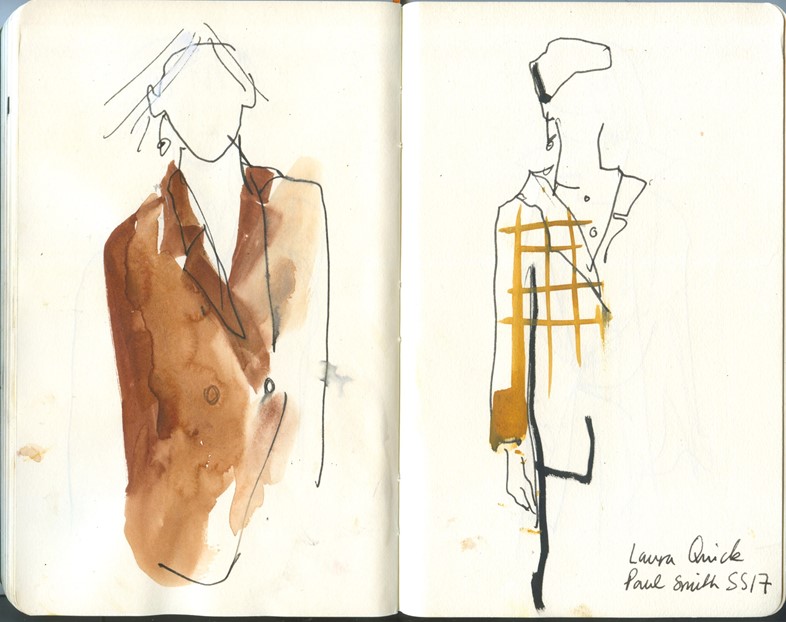

Just as synonymous with Paul Smith’s brand as his stripes, are his shops. Unlike designers whose creative vision came before the challenge of grappling with customers and sales, for Smith shop work came first. “I’ve never been one of those designers who vanishes into an ivory tower and loses sight of the people who buy their kit,” Smith commented. “I started out running my own three-metre-by-three-metre shop in a windowless basement in Nottingham. The rules I had for myself back then still apply today – trying to offer people something exciting and sometimes unexpected,” he continued.

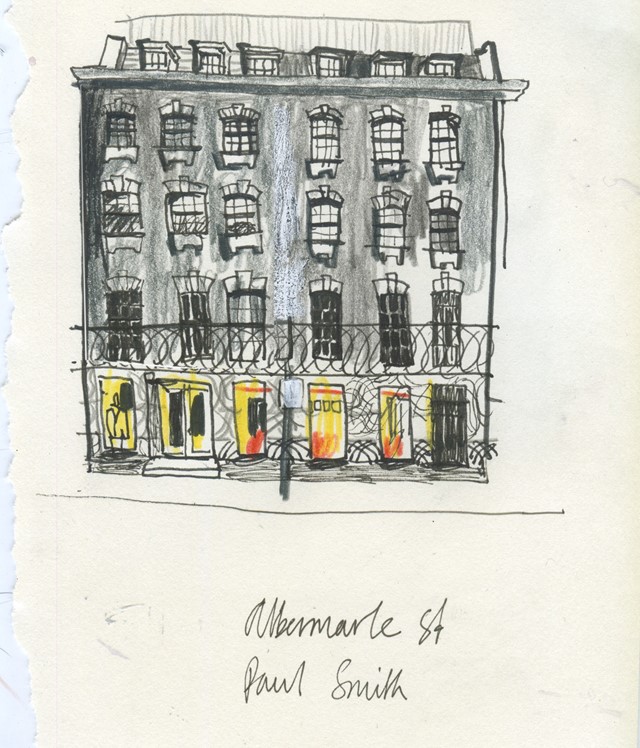

Indeed, every one of Smith’s shops is different, relating closely to its surroundings, its cultural context, not imposing a cookie-cutter design on an established environment, an ethos in line with his brand. “I’m fairly unique in that I have an in-house shop design team,” he said. “Most companies will work with an external agency for that sort of thing. But I work very closely with my team to make sure each shop is suited to its local surroundings – from a bright pink cube on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles that stands out against the pure blue sky, to a Victorian townhouse in Mayfair, London that has a cast iron façade inspired by the metalwork on local lamp-posts and stairwells, every single one is different. I hate the idea of a corporate roll-out!”

However, while all are decked out individually, Smith’s shops also manage to be instantly recognisable as ‘Paul Smith’, echoing his offices in London – a mix of bright, unexpected objects and prints and the lean lines of his suiting. A mirror of his brand, the shops are friendly and fun spaces that always charm, without forgetting the customer – no wonder he sells so many suits. As for why physical retail has the edge over online, he comments, “Online doesn’t have a smell!”

Solange Azagury-Partridge

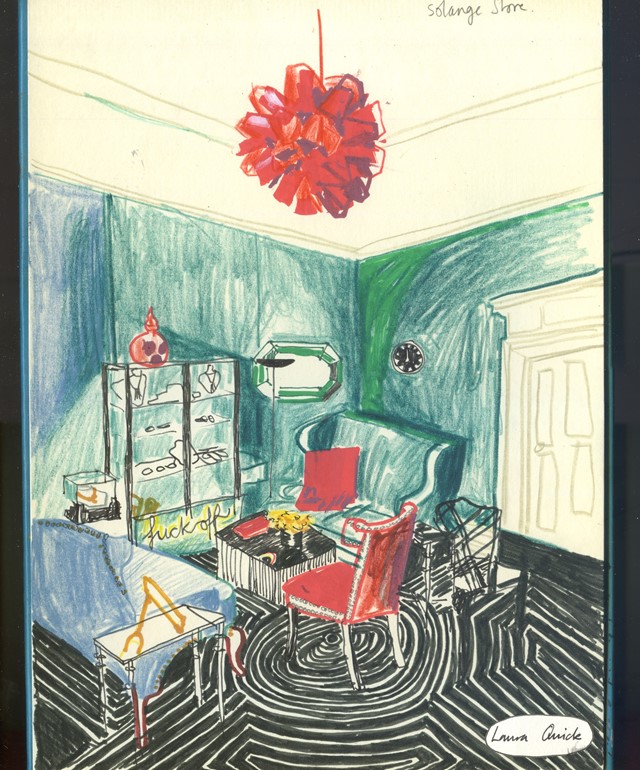

Entering Solange Azagury Patridge’s jewellery shop on Chilworth Street in west London is like walking into a deep green, velvet-walled jewel box. The light comes in through brightly-hued stained glass windows, and an array of rainbow coloured jewels glitter from cabinets all around. It’s a cosy space, with just enough room to pick out what you want to try, and a few sofas to sit down and play with the pieces – a far cry from Azagury-Patridge’s vast, 5000 square foot former site on Mayfair’s Carlos Place, situated among the likes of Roland Mouret and Christopher Kane.

Here, the jeweller has no shop sign and there are no other luxury shops on the street, indeed, it is not a luxury-shopping destination, period. So, why scale down, other than the obvious drop in rent? “The move was driven by the need to live a life led by freedom and imagination. My enormous shop on Carlos Place was beautiful but ended up feeling like a burden,” Azagury-Partridge recounted. “This move was a totally personal choice that is not in a location anyone else would ever choose to be. It's close to my home. It's convenient, easy and relaxed as well as being financially and emotionally low maintenance. If my clients need to come to the shop for whatever reason, it's just as easy for them to come here as it would be to Mayfair or Knightsbridge.”

Having a smaller shop for Azagury-Partridge is about having a business at the scale at which she lives her life. The Chilworth Street site is round the corner from her home in Bayswater and allows regular, direct contact with clients, many of whom are local. It’s also a reaction to the situation when she was owned by Labelux, who wanted to scale the business up and up into a global mega brand, which didn’t feel right to her. Since Azagury-Partridge bought back 100 percent of her company in 2012, she has set about re-shaping it to reflect her personal ethos, and for her, that process begins with setting up shop in the right way.