When I first met Zoe Bedeaux, I was struck by many things. Firstly, her appearance: besides being outstandingly beautiful, her dress sense is impossible to replicate because it is so inherently individual. Bedeaux’s aesthetic transcends time; she mixes Ossie Clark dresses with Pakistani textiles and a liberal application of jewellery. As a stylist, she is renowned for her eclectic ability to combine vintage clothing with the contemporary – a skill which, over the years, has led to her working with publications from The Face to Vogue.

It is not just the superficial that makes her so magnetic. Bedeaux's wit is infectious: she is a fountain of knowledge, and a cultural chameleon. Over the past 25 years, little has taken place in London that she hasn’t been a part of in some way. Now, however, with her two children having grown up and left home, she is focusing on her own work – a series of short stories and a book of prose entitled From The Mouth of Babes Speak I, which she will showcase in the autumn, and which we have previewed in a film clip here. I visited her home to find out a little more about her background, and how the atmosphere of the fashion industry has shifted over the career.

When did you move to London?

"I moved to London when I was 17, after spending a year on a foundation course at Harrow School of Art – the idea was to take a year out and then go to St Martin’s to study Fashion Journalism. Instead, I did a few internships, one at Elle and the other for the PR Marysia Woroniecka. Marysia was the hottest PR in London; she looked after Richmond and Cornejo, Nick Coleman, The Antwerp Six… to name a few. She had a very interesting roster, and a great eye. She was based in Chelsea, and all the girls who worked with her ended up at the 'more established' magazines like Vogue. There wasn’t a job going with her at the time, so she recommended me to Camilla Lowther – then I met up with her and we clicked. Camilla had offices near to Portobello Road, and represented a lot of the people who worked with the magazines that I read growing up – people like Mark Lebon, who worked with Ray Petri.

I was really interested in Ray’s work, and had even written to him when I was 15 – but the letter was returned to sender as he’d moved. Anyway, I became Camilla’s PA and basically did everything from casting to full-on production. It was weird to suddenly be immersed in a world full of all the people I had been reading about – I wasn’t the girl trying to get a job at Vogue, I wanted to work with people who created imagery that made my heart skip a beat. I wanted to be among those people who I considered visionaries, people who were breaking boundaries. Ray globalised fashion, he brought colour to the frame and defined what Britain is all about: a big melting pot of culture. As a young person growing up during that time, it was very important to be represented visually. I sometimes wonder what the fashion landscape would be like today if Ray had lived; his work is constantly being excavated. His voice was so important."

"I wasn’t the girl trying to get a job at Vogue. I wanted to be among those people who I considered visionaries, people who were breaking boundaries." Zoe Bedeaux

How did you meet Ray?

"I finally met him towards the end of his life and produced one of his last shoots, for Jockey underwear. He was amazing. I remember sitting next to him at one of Rifat Ozbek’s screenings – Rifat used to show his collections on film and John Maybury would make these amazing kaleidoscopic blue screen films which were fantastic. Ray turned to me and said, ‘you should be in this show’. The next season I was in the film, but unfortunately he had already died."

You must have seen a lot of friends pass away at that time.

"Yes, it was a surreal and sad time; people just disappeared. When Leigh died it was so sudden. I loved that man – I didn’t know him for very long, I had met him on a weekend away in Italy with Rifat Ozbek and some friends – I remember he had this day look: a sedate grey suit and a greyish wig. The next day, we went to the beach and he was swimming in the sea with his wig just floating next to him. He was a sensation – so funny. He got out of the sea and had a nap and when he woke up, he said that he’d had a prophetic dream about me, which was weird because I didn’t know him very well at all. He said he saw great things ahead of me. At the end of the weekend, he told me that I was the most eccentric person he’d ever met. I thought that was rich coming from him!"

Can you talk to me about how your career came about after working at CLM?

"Back then London was on fire and everything and anything was possible. When I was working at Camilla’s, I looked after Judy Blame, but I then left and moved to Paris. When I came back to London, I asked if I could work with him as his assistant – I loved what he was saying visually and we really got on. It was the early 90s and he was working with Neneh Cherry and Massive Attack, alongside doing lots of editorial.

Going to shows back then was amazing; they were a spectacle, but it went beyond that. You were viewing something that you hadn’t seen before, things that nobody had ever seen before. Rarely now do I see something in fashion and think, ‘wow, that’s amazing and original.’ It’s weird because I was never into ‘fashion’ in the sense of ‘the industry’. I love clothes, I love style, but fashion doesn’t appeal to me. Today fashion is very backwards in going forwards – I feel like I’ve seen it all before, which contradicts the very definition of fashion. That’s why working with someone like Judy was so great, because he’s a visionary. He has his own dialogue; the shoots were a visual commentary and there was always a backstory to the story that was not necessarily obvious."

"Going to shows back then was amazing; they were a spectacle, but it went beyond that. You were viewing something that you hadn’t seen before, things that nobody had ever seen before." Zoe Bedeaux

So do you think things are different now?

"Today if you go on a fashion shoot, the whole brief has been discussed: the designers have been chosen, the editor will have stipulated who has to be used. There is a different energy propelling the vehicle of fashion today and that energy is money. It’s clear that you’re selling something – that’s the point now. Before, I would go on a shoot and we didn’t know what would happen; things were very spontaneous. It was about the synergy of all of the people and what each person brought to the shoot. We were working together to create fierce looks. We used whatever we wanted; we weren’t trying to sell clothes.

You have to remember that the luxury market wasn’t part of the repertoire in the same way that it is today. Luxury brands catered to the rich, the handbag was yet to be crowned queen. Perfumes and bags brought the luxury brands into the open market, and now it’s what everyone aspires to – be it the real thing or imitation on the high street. Judy used to play around with all of those luxury brands, cutting up their logos and rebranding them – brands like Moët, Chanel and Vuitton. i-D used to print letters that were sent in and Moët sent one in saying that they were looking for Judy – they wanted to prosecute ‘her’! I find it amusing that Judy recently went on to work for Louis Vuitton, as a consultant for Kim Jones showcasing the work of fellow Seditionary Christopher Nemeth, who was wanted by Royal Mail for his destruction of the Queen’s property. He would cut up Royal Mail sacks and use them in the construction of his early jackets. It’s all so wonderful, you couldn’t make it up!"

How would you describe your womanhood?

"I was a tomboy so I connected with my femininity much later in life – because I spent so much time with the boys, I saw myself as one of them. I didn’t realise that being a woman had its obstacles; I was brought up thinking that you could do whatever you wanted in life, that colour or gender were not to be a hindrance. I'm very much in touch with my animus and, from a performative perspective, I play around with that; I like to flip the script."

How did the film that you’ve been working on come about?

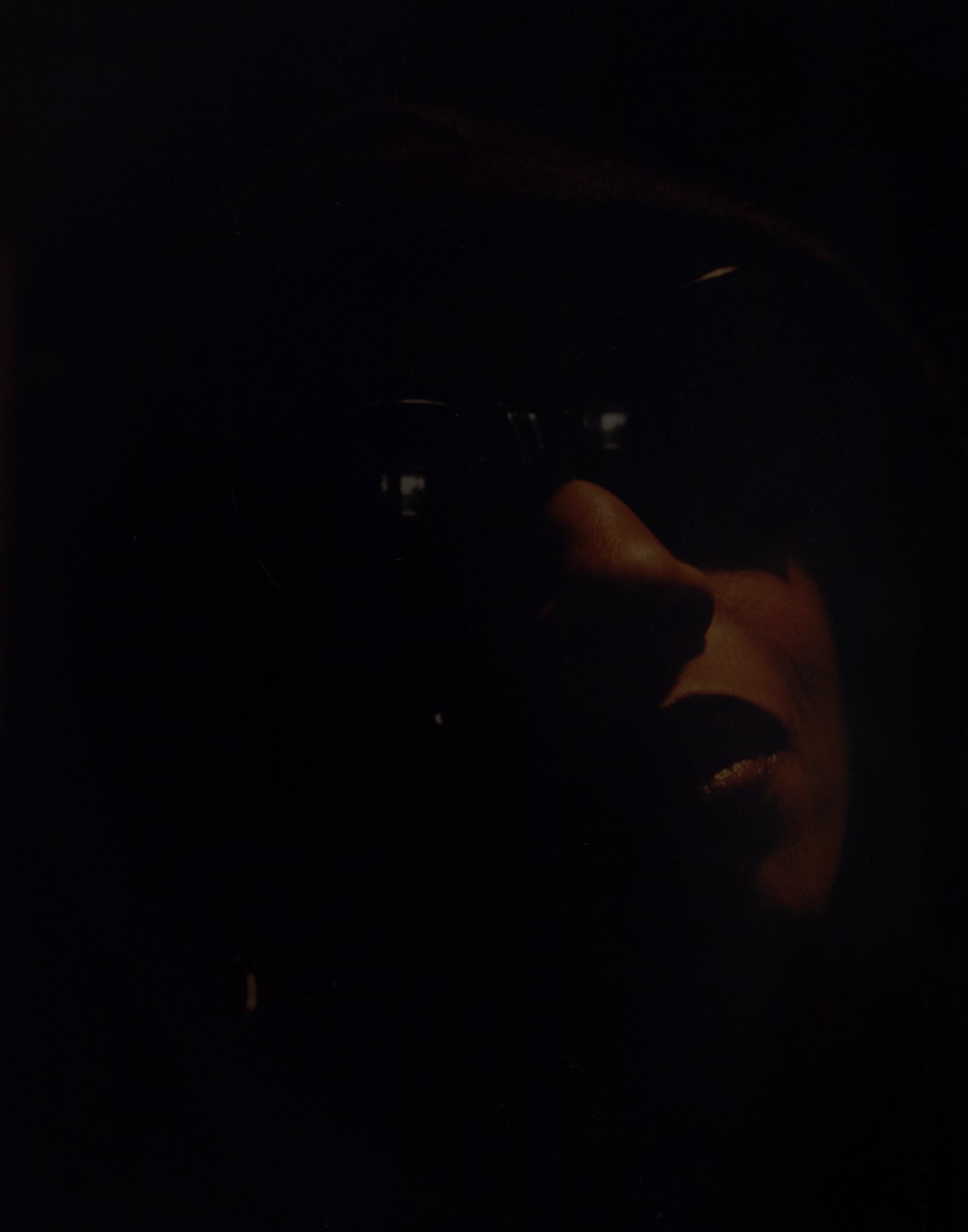

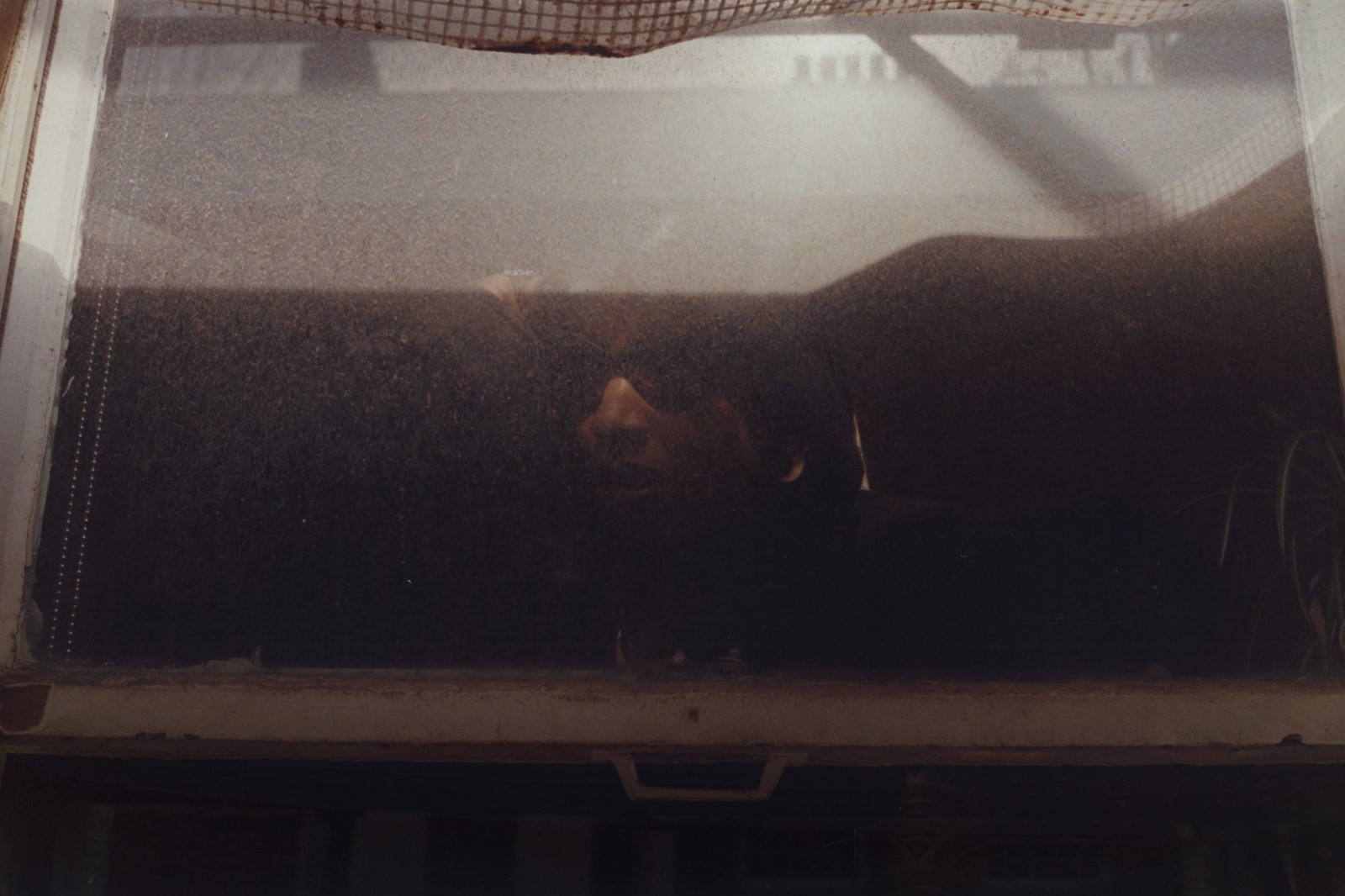

"I made a soft sculpture which was exhibited in a group show two years ago. I named the piece From The Mouths Of Babes Speak I but I didn't want to sell it because I knew that I wanted to work with it further, so I marked it sold. I’m not a performer – in fact, I call myself a non-performance artist – but I had all of this material that I wanted to bring to life and From The Mouths Of Babes was the perfect vehicle. I just had to figure out a way to do it without feeling too personally exposed, and make-up provided the perfect camouflage. My friend Janeen Witherspoon came and did a make-up trial, which took hours as it had to be just right. I asked my friend Jez Tozer if he'd come over and take some stills and shoot a bit of film and that was it! From the Mouth of Babes Speak I will be presented as a live show later this year."