In honour of Fendi's imminent S/S16 show, we consider how the unsung Swiss Dadaist Sophie Taeuber-Arp inspired the house's A/W15 collection, in this revealing extract from the latest issue of AnOther Magazine

This year, the house of Fendi is celebrating its 90th anniversary, as well as 50 years of collaboration with creative director for ready-to-wear and fur, Karl Lagerfeld; a relationship between a maison and designer longer than any other in the fashion industry.

The history of the house is rich with artistic endeavour, both on the part of its designers and that of its associations. For the last few years, the collections have taken inspiration from art history and from particular artistic movements concerned with geometric patterns. Playing with graphics was part of the house aesthetic in previous decades, too. In 1965, Lagerfeld designed the beautifully distinctive double-F logo, a simple but puzzle-like formation: one upright F faces another inverted one to complete a rectangular shape.

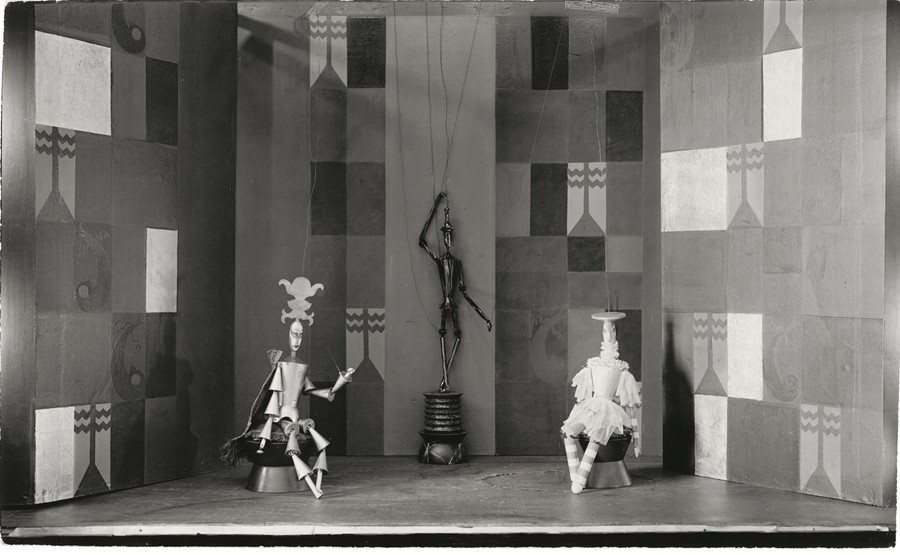

For A/W15, Fendi worked with the Sophie Taeuber-Arp Foundation to draw out the ideas of this interdisciplinary, early 20th century Swiss Dadaist. The set design for the show reproduced details of her graphic abstractions while recreations of the animal puppets she made for a performance of Carlo Gozzi’s The Stag King, commissioned by the Zürich Museum of Arts and Crafts in 1918, feature in the current Fendi advertising campaign.

Taeuber-Arp, who was highly respected and beloved by her peers and whose distinctive production influenced their practice at the time, has been less well recognised in the modern art canon, as Lagerfeld observed after the show in February. In part this is because her practice was wide-ranging: from sculpture and painting to performance, puppetry and textiles. Her broad working interests, however, reveal something important: as she would repeat and carry over individual designs between textile, paint, sculpture and performance, they became mobile symbolic gestures unreliant on a single form to retain their significance.

She was concerned with the translation of content between forms and structures, an inclination towards fluidity that might seem unexpected for an artist whose imagery was composed of inelastic geometries. But by taking the grid-pattern principles of decorative textile design into painting – from applied to fine art – she profoundly challenged traditional beliefs about art and its meaning, as well as freeing the artistic expression itself of restricting precedents. As art historian Nell Andrew wrote in the Art Journal last year, “Her work in every medium calls attention to the dynamics of space, rhythm and balance. It refers to dance.” Having trained in dance with the radical choreographer and theorist Rudolf Laban and befriended Mary Wigman, one of the founders of modern dance, Taeuber-Arp was instructed at the forefront of avant-garde changes to this medium, just as it was moving from a proscribed repertory and technique into a radically new system concerned with spatial and bodily relations. The dancer would become an object to be manipulated; identity and meaning constructed through gesture.

Abstraction was revolutionising painting and dance at the same time in Europe between 1910 and 1920, and Taeuber-Arp combined the two in her practice. She was photographed in 1916 dancing either for the Cabaret Voltaire or for the opening party of the Galerie Dada in Zürich, costumed in a Cubo-Dadaist collage of primitive forms with long, stiff cubes as sleeves and a mask as headpiece. These two integral sections of her costume covered the conventionally expressive parts of a dancer’s body, and in the photograph she resembles a puppet held in mid-air, as if on a string. Yet, when she moved, it was “with a grace not of this earth” as her contemporary, fellow Dadaist Hans Richter, described her.

The interdisciplinary nature of her work meant that she could draw on dance and textile design to further her art: the austere and angular lines of the costume were carried by her supple body with style; through the relationship between new modes of movement and pure colour, line and form, gestures became unfixed from their previous meanings. It also meant that her art was “durational”: a live performance, witnessed but not captured in motion, it was later re-staged for a still photograph to give some small access to past action.

It is a fitting addition to her legacy that, as the place and nature of live fashion shows are debated today, Fendi has evoked the powerful practice of Taeuber-Arp, in whose imagination and output there was no doubt that by bringing together the different media of textile and performance, each would affect and inspire the other for the better.

This article appears in the A/W15 edition of AnOther Magazine.