Apparently, we know more about the surface of the moon than we do the bottom of the ocean. The pickled menagerie currently on show at London’s Natural History Museum, certainly confirms that there’s far more going on beneath the waves than most of

Apparently, we know more about the surface of the moon than we do the bottom of the ocean. The pickled menagerie currently on show at London’s Natural History Museum, certainly confirms that there’s far more going on beneath the waves than most of us dream of. Included in The Deep, an exhibition chronicling the history of deep-sea exploration, sealed glass jars contain the preserved bodies of sea beasties with vampire teeth, too many legs and barbed shells. They might as well be from outer-space they’re so exquisitely alien.

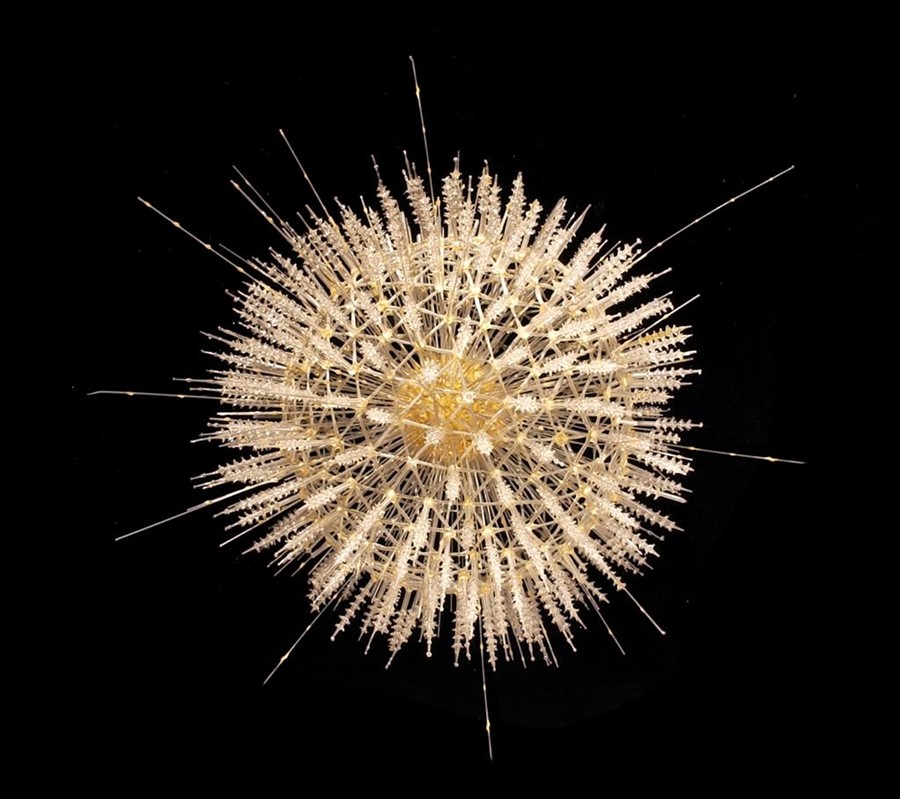

Yet, some of the most elusive exhibits here originated on dry land. Humbly displayed in a small glass case towards the show’s finale, one is about the size of a tennis ball and looks both as light as the flimsy tendrils of a dandelion head and as prickly as a fist full of needles. Lying next to this marvel, are equally diaphanous twins: crystalline bulbs that sprout delicate tentacles. Though as translucent as a jellyfish, they seem frozen. Look close and you can see they’re made not of organic matter, but of glass. Impossibly intricate in construction, these are two of the Blaschka’s rarely seen models of sea life.

Through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this Dresden-based father and son duo, Leopold and Rudolf, created thousands of such replicas of anenomes, squids, sea slugs, starfish, sea cucumbers, jellyfish and far more, for museums across the world. Originally in the business of glass eyes and ornaments, Blaschka junior’s passion for the burgeoning discipline of natural history lead them into uncharted realms for glassworkers. They developed extraordinarily refined techniques for simulating sea life at a time when it was otherwise impossible to preserve the delicate boneless and transparent bodies of the creatures marine explorers were fishing from the depths. To this day, no one knows exactly how they did it: when Leopold died childless he took the secret of their art to the grave.

The Deep is at the Natural History Museum , London until September 5.