We talk to the 2018 Hyères fashion prize winners as they show their latest collection at this year’s festival

- Who is it? Paris-based label Botter, winner of the 2018 Hyères fashion festival

- Why do I want it? Climate-conscious clothing which draws on designers Rushemy Botter and Lisi Herrebrugh’s Caribbean origins

- Where can I find it? At Botter’s online store; coming soon to Selfridges and Dover Street Market

Who is it? It’s a year since Rushemy Botter and Lisi Herrebrugh – collectively, Paris-based label Botter – won the Hyères fashion prize, and they are back at Villa Noailles, a vast Modernist property in the south of France where the festival is set (once upon a time Picasso and Jean Cocteau holidayed in the Robert Mallet-Stevens-designed home). The evening before, they showed their latest collection; now, they are in Mercedes-Benz’s ‘The Formers’ showroom, alongside those they competed against the previous year. “It’s nice to relax, you know, we’re not having the stress of the competition,” Botter laughs. “It’s such a special place; everybody has their own world, and their own vision.”

The last twelve months have been a whirlwind: in July, they showed a co-ed collection at Berlin Fashion Week, supported by Mercedes-Benz and their Fashion Talent program; that August, storied Parisian house Nina Ricci named Botter and Herrebrugh creative directors. (They also join the Hyères panel, led this time by Natacha Ramsay-Levi, creative director of Chloé.) “I think we are trying to make it all a bit more polished,” Herrebrugh explains of the latest collection, which in part documents this displacement: from just-graduated students to the vaunted salons of Paris’ Avenue Montaigne. “With this collection I think you can really see already that we moved to Paris and are working for a big house,” she says. (Accordingly, T-shirts and sweatshirts are printed with ‘Botter in Paris’.)

Living in Paris also revealed to Botter and Herrebrugh (who each have links to the Caribbean, he grew up in Curaçao, she lived between Dominican Republic and Amsterdam) a very different side of the city, too: the waves of refugees from various countries, each adapting to situations far away from home and building a new life, often with discarded objects and clothing. “I think it’s about these people working with what they have,” Botter says. “That’s the story we were trying to tell; we’ve always tried to create something from the things we already have.”

Why do I want it? Their Autumn/Winter 2019 collection showed new refinement – something they attribute to support from last year’s festival, where alongside the monetary prize they were able to select one of Chanel’s Métiers d’Art, the various craft arms of the house who make buttons, hats, embroidery and the like. Botter and Herrebrugh chose Atelier de Verneuil en Halattes, the factory where several of Chanel’s most recognisable handbags are made – including the 2.55 – to create their “upside-down bag”, a leather bag with an “upside-down” handle and B-for-Botter clasp. “In the factory there are just Chanel bags everywhere,” says Herrebrugh. “You just see the women working and it’s really special.” (At the fair they also released a short film which detailed the complex process, directed by Alexandre Silberstein.)

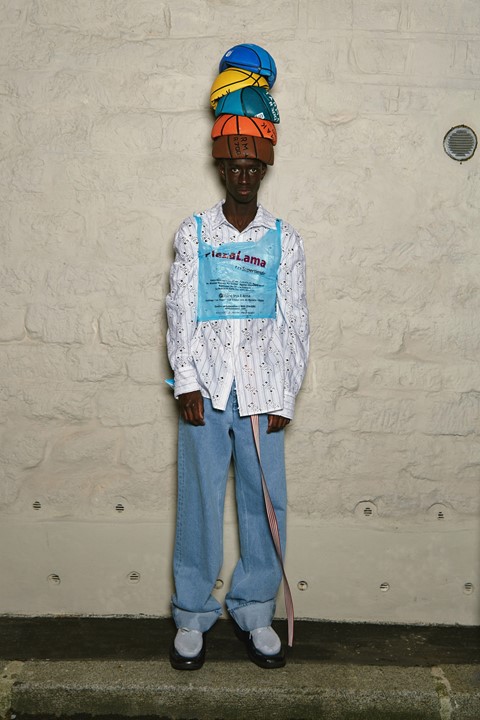

Elsewhere, this upside-down motif – in part inspired by the make-do attitude of Paris’ marginalised communities – was translated into deconstructed outerwear and shirts, where panels were placed top-down and adjusted by toggle fastenings. A top, in plissé fabric, was inspired by the shape of a plastic bag, while oversized bonded polo shirts were left raw at the seams, as if made from torn-up leftovers. The playful elements that won the Grand Prix at Hyères – piled-up caps, inflatable dolphins and the like – returned, reimagined for a real-life consumer (the dolphins, for example, had now shrunk to the size of large keyrings). “We wanted to make it a little more wearable,” says Botter. “You know, we need to be in stores and it needs to be an appealing for the customer.”

And, though technically menswear, the pieces are just as easily adopted by women – Herrebrugh is often seen wearing Botter pieces, and their show in Berlin was co-ed (Mercedes-Benz support the winners of Hyères with a unisex show in the city; next season, they will support the 2019 winner Christoph Rumpf). Part of this is down to their joint roles: Botter will undertake the original sketches, while Herrebrugh will look at the pieces once they are on a mannequin. “I like to approach his [Botter’s] designs very technically,” says Herrebrugh. “We work all day together, but he is more about the atmosphere, the story.”

Part of that story is ecology – their Grand Prix-winning collection at Hyères contained plastic fishing nets and the Shell logo (minus the S), each a nod to ocean pollution. This time, they thought about people protecting themselves from the changing climate: an installation at the Villa Noailles recalled the shaded seaside yard of Botter’s grandmother in the Carribean; the notes referred to sealife who have lost their natural homes, forced to reside in bottle cups or drinks cans. “We respond to what we see around us,” says Botter. “Our collections are like a diary.”

Where can I find it? At Botter’s online store and stockists worldwide.

With thanks to Mercedes-Benz.