Tomorrow, Jacqueline du Pré’s widower conducts a special concert to mark the 30th anniversary of her passing. Here we pay the cellist a small tribute of our own

“Jacqueline du Pré was a creature like none other: musically, cellistically and as a personality. Some things, very few, but some things are beyond words. And Jacqueline du Pré was beyond words,” says Toby Perlman in a new BBC4 documentary directed by Christopher Nupen. The hour-long film is comprised of archival footage from five of Nupen’s previous works on the late Du Pré, made prior to her premature death in 1987 from Multiple Sclerosis. Perlman, the partner of violinist Itzhak Perlman, was just one of the notable figures close to the cellist during her lifetime, which saw the musician rise to garner a widely accepted status as one of the most precocious musical talents of all time.

Renowned for her visceral and emotionally charged performances, which eschewed the logical and often po-faced attitude of classical music, Du Pré’s convulsing body appeared to become possessed by Dvořák, Brahms and, perhaps most notably Elgar, as she played his melancholic Cello Concerto in E Minor, a piece of music now synonymous with her gut-wrenching interpretation. Tomorrow, her widower, composer Daniel Barenboim, conducts a concert at London’s Southbank to mark the 30th anniversary of her death. Here, we pay Du Pré a small tribute of our own.

Defining Features

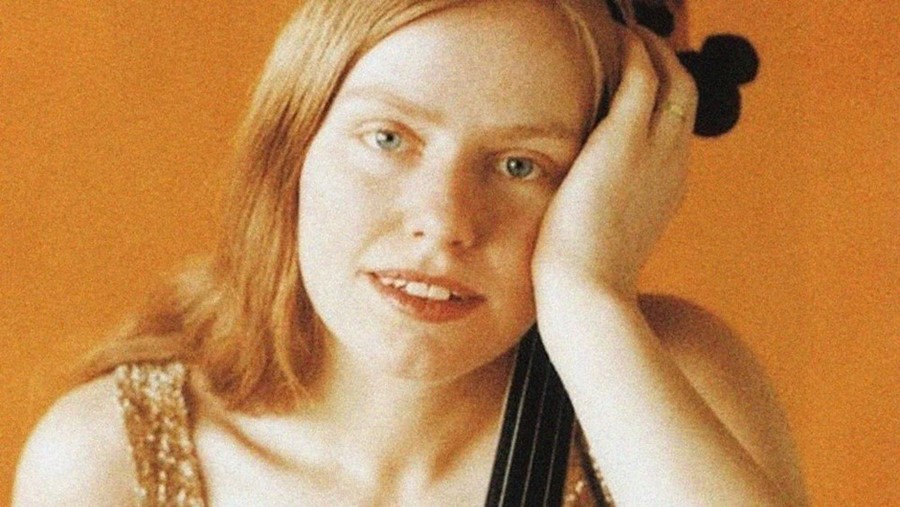

Du Pré was known as one of classical music’s most striking women, described by those who knew her as ‘Juno-esque’. Her pale complexion was offset by a mane of thick straw-coloured hair that fell about her face as she performed. Equally fair lashes and highly expressive brows framed her watery eyes. As musician John Williams recalls: “She was a bit like a schoolgirl, totally open, rather jolly – but she had these shrewd, discerning eyes. Someone else’s eyes in her round jolly face.”

She reached adolescence during the early 1960s, and wore clothes that were befitting of the era, yet also had many specialist gowns made for her to perform in, the designs lending themselves to the particularly spasmodic movement of her body. Later in life, after she married the Israeli-Argentinian Barenboim, she adopted a European-sounding accent, leaving a cut-glass English twang behind her.

Seminal Moments

Du Pré first picked up a cello at the age of six, and went on to enrol at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama at ten after winning an award that allowed her early entrance to the institution. Here, she learned her craft with the famous cellist William Pleeth, who she fondly nicknamed her “cello daddy”. She later studied under various world-famous classical musicians in Europe and Russia, with Mstislav Rostropovich exclaiming she was “the only cellist of the younger generation that could equal and overtake my own achievement”. With a particular skill for memorisation, Du Pré would instinctively learn her pieces without the need for much rehearsal, which allowed her to play with the kind of emotion, expression and command of her instrument that most cellists never achieve. Her debut performance took place at London’s Wigmore Hall at the age of 16, and four years later she would go on to record the now famous Elgar Cello Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra.

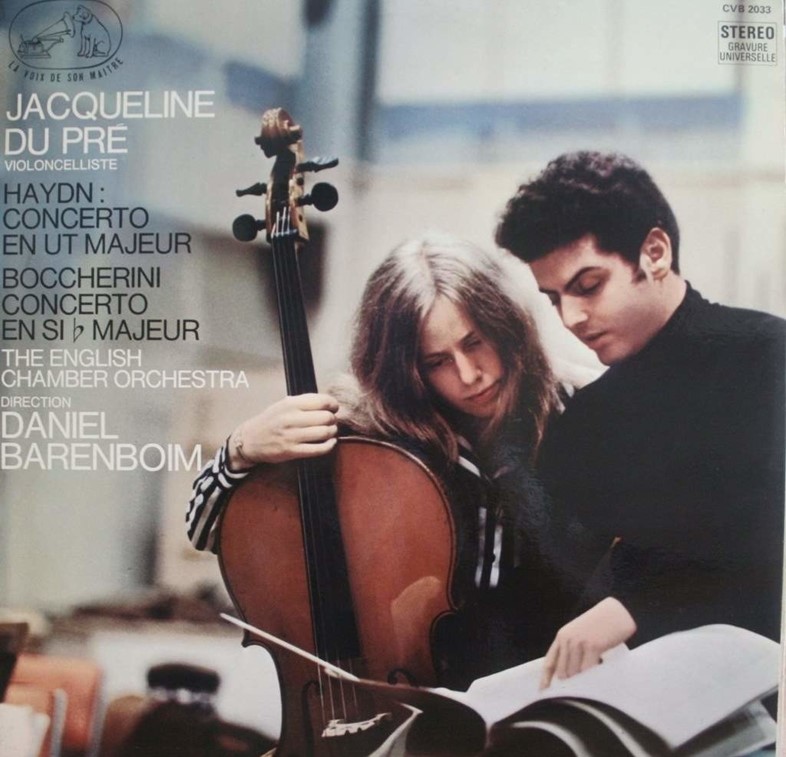

Not long after studying in Russia, Du Pré met pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim (incidentally, while they both had glandular fever) and the two fell deeply in love. “Instead of saying good evening we sat down and played Brahms,” the musician recalled of their relationship. She soon converted to Judaism, marrying Barenboim in Jerusalem a while later. The pair would often draw comparisons between Robert and Clara Schumann through their outstanding collaborative work.

But, tragically, it wasn’t to last. By 1971 Du Pré’s playing began to falter: she could no longer feel the strings or the weight of her bow and was prone to bouts of clinical depression. Diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis, Du Pré was robbed of her ability to play the cello by the age of 28, ultimately ending up wheelchair-bound and unable to feed or dress herself. Her body – once such an integral part of her performance – had ultimately failed her. She passed away at the age of 42. After her death, a book titled A Genius in the Family was written by Du Pré’s siblings Hilary and Piers. In 1998, it was turned into biopic Hilary and Jackie, starring Emily Watson as Jacqueline and Rachel Griffiths as Hilary. Despite the film receiving high praise from critics – Watson and Griffiths each received Best Actress and Supporting Actress Academy Award nominations for their challenging roles – it was also met with furore from those who knew Du Pré personally, with director Anand Tucker accused of over-dramatising Du Pré’s life.

She’s an AnOther Woman Because...

Du Pré’s unyielding love for performance broke with formal conventions of classical music, imbuing concertos with a romantic spirit, not least through her expressive and frenzied bodily movements which were often met with criticism and shock. Nonetheless, she continued to work in her own way until she was no longer able, with the bow of her cello communicating something truly transcendent. In her personal life, Du Pré was known for her unashamed honesty and openness, reflected in the candid performances that have moved even the most stoic of men into tears. “She didn’t give people what they wanted, but she gave people who she was,” says Nupen’s documentary.

Daniel Barenboim and West-Eastern Divan Orchestra perform at the Southbank Centre, London, on October 28 & 29, 2017.