As a compelling new documentary about the extraordinary life of the intrepid explorer arrives in the UK, we examine her forgotten legacy

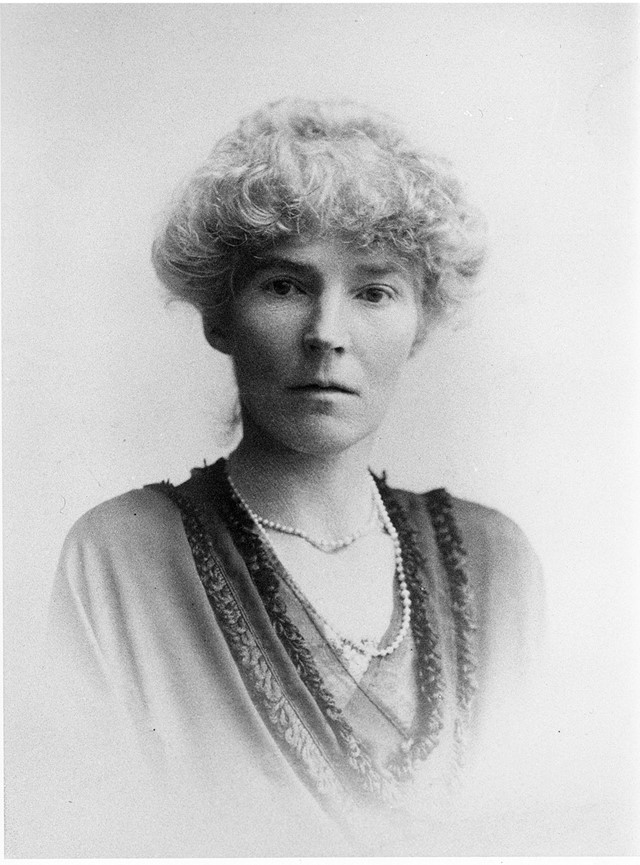

Who? Writer, traveller, archaeologist, diplomat, spy – Gertrude Bell was at one time described as “the most powerful woman in the British Empire”, her legacy acknowledged as being more profound than that of her revered contemporary T.E. Lawrence (AKA Lawrence of Arabia). Yet, as a female in a male dominated world, her death in 1926 saw her myriad political and cultural contributions swiftly forgotten, and today her name is most typically met with a blank stare by anyone who hasn’t encountered Werner Herzog’s (critically panned) 2012 biopic Queen of the Desert, starring Nicole Kidman as the intrepid explorer. However, as a new documentary Letters from Baghdad hits cinemas in the UK, we take the opportunity to pay homage to the female adventurer that time forgot.

Bell was born in 1868 in Durham to a wealthy industrialist family. Her mother died when she was just a child, but she fostered a cherished relationship with her father, stepmother and four siblings throughout her life, frequently writing letters home and punctuating her travels with visits to the family abode in Yorkshire. She attended Oxford, achieving a first class honors degree in history, and in 1892, shortly after graduating, embarked on a trip to Tehran, where her uncle was serving as British minister. She was beguiled, and thus began her lifelong love affair with the Middle East. A quick spell in western Europe ensued thereafter, during which time she indulged her inner-thrill seeker while deftly clambering mountain summits; before long she had returned eastwards hell-bent on adventure.

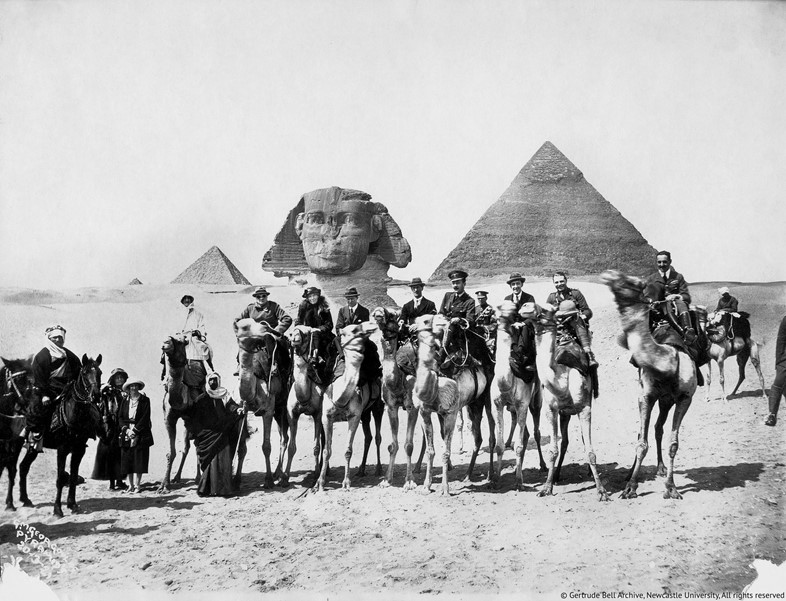

“I prefer the East to the West,” Bell wrote in one of her evocative, early correspondences. “You will find… a wider tolerance borne of greater diversity. A man may go in public veiled up to the eyes or clad, if he pleases, only in a girdle. He will excite no remark. Why should he? He’s only obeying his own law. So too the European will be wiser if he doesn’t ape their habits. He will meet with far greater respect if he adheres strictly to his own.” From the start, as her words evidence, Bell was blessed with an inherent understanding of the traditions and the people she encountered, and how best to gain their confidence. The letter also explains her insistence in wearing fashionable and elaborate clothing regardless of her location. In countless images, taken over the years in the sweltering desert climes, she is decked in long, heavy dresses, while draped in white pearls and fur stoles, her pointy featured face topped with eccentrically feathered hats.

What? Over the next 20 years, Bell voyaged extensively through the Middle East, taking photographs, attending archaeological digs, honing her Arabic and befriending locals, both rich and poor, to gain a greater awareness of the inner-workings of their countries. She began writing travel books to inform the British, with unprecedented detail, about the far-flung corners of their then-empire. Such was the extent of her knowledge that she was recruited by the British Intelligence during the First World War to help guide soldiers through the deserts and in 1917 she was appointed Oriental Secretary of the Arab Bureau in Cairo, tasked with forging alliances with Arab tribes alongside T.E. Lawrence. When the war ended, she was kept on by the British Government as a diplomat and was involved in the delineation of Iraq’s borders and the establishment of the state. Her tact and fluency in Arabic saw her assume the position of mediator between the Arab government and British officials and she was the only woman invited to attend the Cairo Conference of 1921, hosted by Winston Churchill, where her opinions on the future of Middle East were keenly heard.

She remained in Baghdad after King Faisal I’s appointment that same year, and became the Director of Antiquities – a role which saw her construct the city’s now famous archeological museum, filling it with the country’s treasures, which she believed should be preserved in situ rather than transported to European centres of learning as they had been previously. Sadly, however, her dwindling political involvement, earlier misfortunes in love, and an ongoing battle with depression, which she described as a “black cloud”, saw her take her own life two days before her 58th birthday.

Why? After years of relative unknown, Bell is finally being given the recognition she deserves in a new documentary by Zeva Oelbaum and Sabine Krayenbühl. The elegantly shot film, titled Letters From Baghdad, features an unseen Tilda Swinton as the voice of Bell, reading extracts from over 1,600 of her compelling letters and evoking her complex personality – by turns determined, troubled and romantic – with a moving vitality. An array of actors play her friends and colleagues in a collection of mock interviews, while never-before-seen filmed historical footage from the Middle East, and many of Bell’s accomplished photographs, enliven these accounts.

Letters from Baghdad is in select cinemas nationwide now.