As Somerset House prepares to stage a blockbuster exhibition of artworks inspired by Kubrick's inimitable vision, we explore the impact and legacy of the film provocateur

When Stanley Kubrick paired soaring Beethoven with depraved violence in A Clockwork Orange (1971), audiences were shocked. He was behind so many innovations in cinema that “Kubrickian” has become a shorthand adjective for touches inspired by him, from anachronistic music to the fluid camerawork he favoured. Homages and parodies of iconic scenes in his films are endless, and directors from David Lynch to Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese and George A. Romero sing his praises. His legacy continues. An immersive new exhibition at London’s Somerset House titled Daydreaming With Stanley Kubrick shows soundtracked installations inspired by the auteur from musicians and artists such as James Lavelle, Marc Quinn and Sarah Lucas. Brush up on his film oeuvre before the doors open with our digestible guide to the director.

Painstaking Perfection

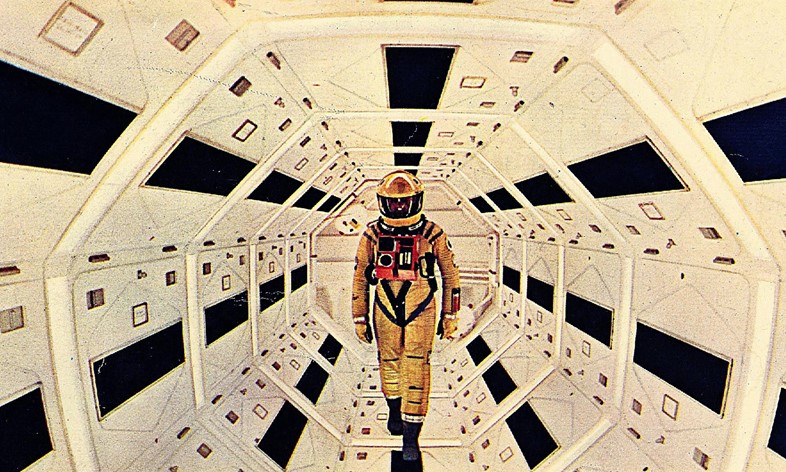

Kubrick is famed – and notorious – for his perfectionism. His obsession with getting every detail just right led him to painstaking research, and he demanded a gruelling number of retakes from his actors. His careful eye led to iconic sets. The bright red modernist Djinn chairs of the space station in slick sci-fi vision 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) are now known as “2001 chairs”. For some scenes of period drama Barry Lyndon – a wonder of cinematography using authentic candlelight – Jack Nicholson is said to have weathered as many as 60 re-tries. After a take Nicholson would ask: “That was pretty good, wasn’t it, Stanley?” Kubrick replied: “Yes it was. Now let’s do it again.”

New Hollywood Audacity

Kubrick was part of the New Hollywood generation of directors. They injected fresh energy into American filmmaking with their risks and taste for young rebellion. His A Clockwork Orange pits vicious teen delinquency against extreme experiments in mind control as the state tries to curb the ways of sociopath Alex (Malcolm McDowell), who has gone on a gleeful crime spree with his gang, fuelled by drug-laced milk. It’s set in a dystopian UK, where its unprecedented violence caused a huge scandal.

The Blackest Laughter

Kubrick often confronted society’s greatest fears – and not without humour. We have him to thank for some of the most surreal, biting black satires of the screen. Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learnt to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) played on prevailing Cold War fears of a nuclear attack, as a bunch of warmongering loons high on testosterone careen perilously close to the button. Kubrick said: “A satirist is someone who has a very sceptical view of human nature, but who still has the optimism to make some sort of a joke out of it.”

Troubling Desires

“How did they ever make a film out of Lolita?” posters for Kubrick’s 1962 take on Vladimir Nabokov’s hugely controversial novel were taglined. He adapted the book – about a middle-aged professor’s infatuation with a prepubescent girl - despite the strict censorship climate of the ‘60s, toning down its salacious aspects. Sexual transgression pops up often in Kubrick’s work. It leads again to an extravagantly absurdist unravelling of bourgeois family life in his final movie Eyes Wide Shut (1999), as fantasies, jealousy and an occult-style secret society tempt a married doctor (Tom Cruise) on an odyssey through the Manhattan night.

Novel Beginnings

For all his innovative spirit, Kubrick favoured adapting films from existing novels or short stories – but looked far and wide for material. Eyes Wide Shut (1999), for instance, grew out of decadent Viennese avant-gardist Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 erotic tale Dream Story. Horror masterpiece The Shining is based on Stephen King’s novel about a recovering alcoholic who unravels at a creepy snowed-in hotel, written when the author was himself battling the bottle. King has said he didn’t like the film – but it has such a massive cult following there has even been a great documentary made (Rodney Ascher’s Room 237) about fan interpretations.

Daydreaming With Stanley Kubrick is on view at Somerset House from July 6 – August 24, 2016.