The textile design icon is the subject of a long-overdue exhibition at Tate Modern – the first ever of her work in the UK

As curator Ann Coxon explains, it is somewhat unconventional to place a loom at the entrance of a major Tate retrospective. “It’s very surprising to have a show that is predominantly textiles at Tate Modern,” says Coxon. “We’ve shown work by Sonia Delaunay, for example, but you start with paintings and progress through to later see that she did something with fashion, but to actually start with a loom, and for it to be all about weaving, is quite unusual for us.”

Born in Berlin in 1899, Anni Albers was a pioneer of textile design, a pivotal educator in her field and one of the poster women for the radical Bauhaus school. Shockingly, Anni Albers at Tate Modern is the first ever exhibition of her work in the UK and has taken curators Coxon and Professor Briony Fer more than two years to complete, working closely with the Alberses’ friend and foundation director Nicholas Fox Weber. “Having known Anni very well, I must say that she feels present today. She would be utterly thrilled,” says Fox Weber, speaking at the opening of the retrospective. He continues: “What Maria [Müller-Schareck], Frances [Morris], Briony and Ann have done is create the single finest Anni Albers exhibition ever, and to make her come alive exactly as she wanted to be – as a great artist.”

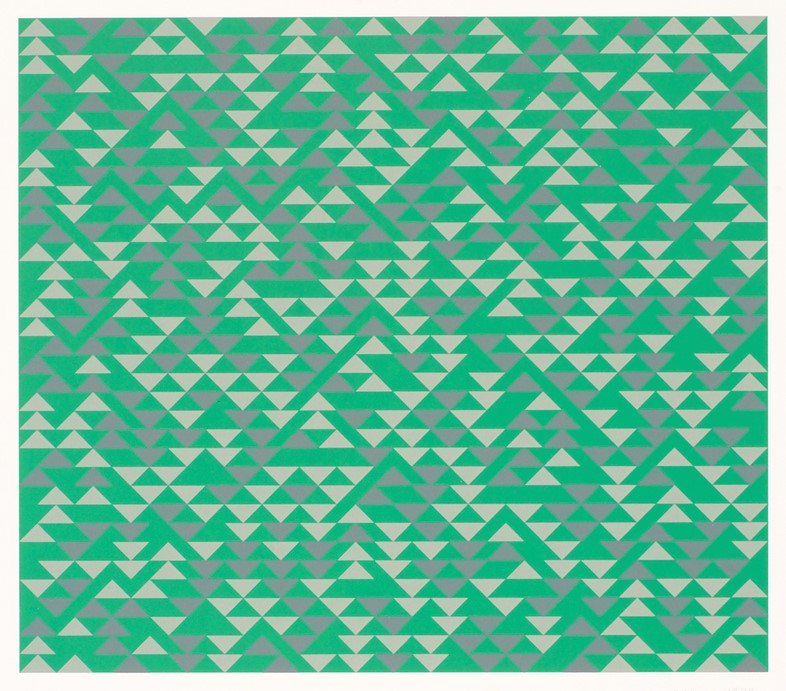

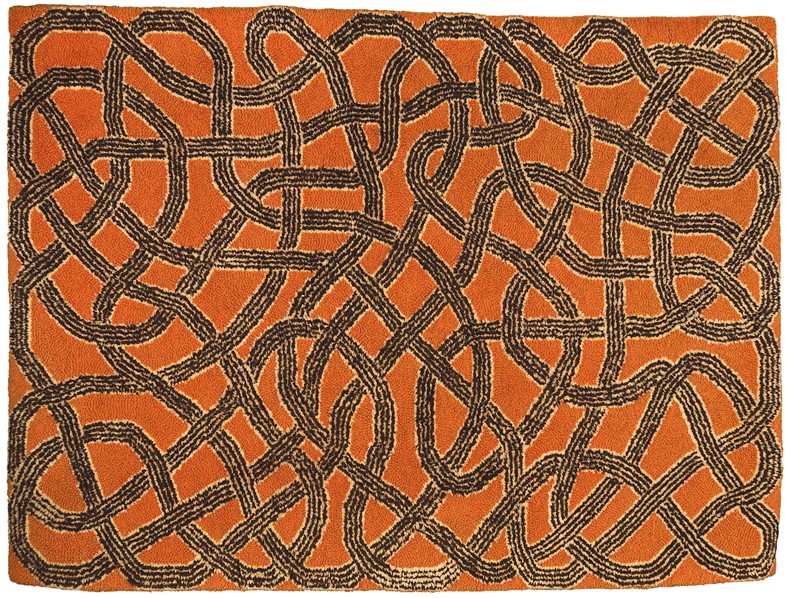

The exhibition, which comes ahead of the centenary of the Bauhaus school, is centred around Albers’ seminal texts, On Designing (1959) and On Weaving (1965). The designer’s approach to handweaving and textile design as a tool for documentation and communication saw her force expansion upon the boundaries of what it means to be an artist. In these texts, she reflects on the history of weaving as a global phenomenon, refocusing it as an artform rooted in skill and technical process. Fusing an ancient craft with the language of modern art, the artist found an untapped opportunity to express the eccentricities of modern living in a medium that dates back millenia.

Despite her career-long devotion to textiles, Albers initially found herself in the weaving workshop essentially by default. Although renowned historically for its progressive approach to design and societal identities, Walter Gropius’ groundbreaking institute was not without its complexities. The female alumni of the Bauhaus are recognised as trailblazers in disrupting gender roles in the worlds of architecture and design, but it has been suggested that some women, such as Albers herself, were steered toward more ‘feminine’ disciplines. “The thing is, the Bauhaus was so formative in these artists’ careers. You know it really gave Anni Albers contact with a medium that became her lifelong passion. And then of course what happened – with the outbreak of the second world war and the rise of Naziism – the Alberses were lucky enough to be offered teaching posts in America so they went off to Black Mountain College and a lot of the Bauhaus teachers moved over the US and spread the movement globally,” explains Coxon as she contemplates the potential for criticism of the school.

“The answer to the gender question, I suppose, is a complicated thing. There are conflicting accounts, depending on what you’re reading, on whether women were actively discouraged from joining other workshops or whether they just chose weaving and gravitated towards it through their own choice. Certainly, there were people like Marianne Brandt who broke the mould and went off and did metal work, but the Bauhaus was an art school. It was a complicated place. Different voices and different influences existed within it and quite often there was conflict of ideas within each workshop – it’s never black and white.”

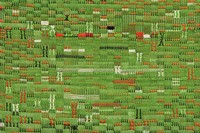

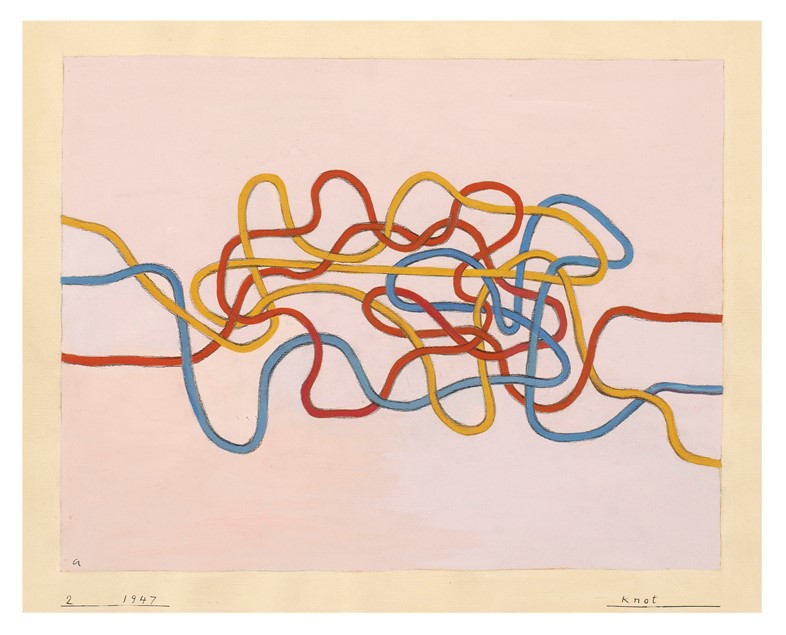

Regardless of any initial gender bias, Albers was deeply passionate about the power of textile and pattern design. Being a student, and later a master, at the Bauhaus, she rubbed shoulders with the likes of painter Paul Klee and her eventual husband, Josef Albers. Klee’s influence is overtly present among Albers’ work, and some of his pieces are even exhibited alongside hers in the exhibition. Albers’ study of weaving transcended cultures and saw she and her husband making regular and lengthy trips to Mexico – 14 in total according to Fox Weber. As her career as an educator developed alongside her work, she would collect samples of local weaves from Mexico, Chile and Peru, amassing an extensive collection of ancient Pre-Columbian textiles. She would, with her students, literally and metaphorically unpick these samples and insist on an exploration of the physical and aesthetic composition of each piece, identifying the stories hidden among each strand.

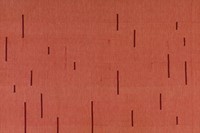

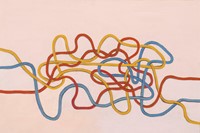

As Albers aged so did her body, and soon the toll of sitting at a loom became prohibitive. With a lifetime of textile work behind her, the designer spent the latter years of her life exploring the art of printmaking. It was an introduction to Fox Weber, who was studying Art History at Yale at the time of their meeting, that proved a catalyst for Albers’ dalliance with print. His father was a printer, and although he explained that the work was commercial, not fine art, she was in awe of the process.

Whether woven or in print, there is a tactility to Albers’ work. According to Coxon, that is what sets this exhibition in a realm of its own. “We’ve deliberately included, at the end, something where people can actually get their hands on materials and satisfy that urge to touch. We’re so much about the visual, our whole existence is through screens. I think it’s really nice just to immerse yourself in something that is much more about the tactile and the handcraft. I think that’s partly why there’s a revival of craft – the urge to go back to thinking about what it means to make something with your hands.”

Anni Albers is at Tate Modern, London, from October 11, 2018 – January 27, 2019.