What we see on film has long shaped our vision of the future, but now, fact and fiction are converging, writes Milly Burroughs

The spectrum of desire that drives the design and architecture worlds has shifted. Where homes were once considered a showcase of wealth and access to the world’s most elusive treasures, they are now a comfortable hub – a chamber within which we find space to cleanse ourselves of life, and clasp moments of calm to our chests, snatched from the chaos and demand of a connected world. For many, luxury has been redefined. It now revolves around adding convenience, function and intuition to the home, inevitably culminating in society entering a state of comatose artificial intelligence reliance, or at least that’s what the film industry would have you believe.

“The future is big business but we have had it in our lives forever and always take it in stride,” says Academy Award-nominated production designer KK Barrett. “Our home thermostat that maintains a temperature and automates heating and cooling. A toaster that pops up when it’s finished. Our phones are highly intelligent, but do they always make the right decisions?” he continues, touching on the uncertainty of a future increasingly built on automation. While the film world has been presenting us with visions of the future for decades, it is only in very recent times that reality and fiction have begun to converge. According to studies from NPR and Edison Research, 39 million Americans owned a smart speaker, such as Amazon Alexa or Google Home, as of January this year – an unfathomable 128 per cent increase from January 2017. So the machines are coming, but what does that mean for design? For centuries, domestic and public architecture have been defined by the physical interactions required to get through the day, but as tasks are indiscriminately transferred to a new breed of ethereal intelligence, the shape of home comforts is unrecognisably changed.

We all think we know what the future looks like – sinuous environments barely pierced by colour, void of decorative appeal but somehow aspirational in refinement – but isn’t that just what we’ve seen at the cinema? Barrett, go-to collaborator of Sofia Coppola and Spike Jonze, has his own thoughts, all heavily influenced by his experience of creating the unnervingly convincing world in which Jonez’s seminal film Her is set. When questioned on the sincerity and accuracy of creating a future world, the production designer highlights the narrow viewfinder through which we are shown it. “Because I am supporting a story and characters, rather than predicting how all of society will absorb new technologies, I address only what touches the character’s world. The bigger picture of advancement in our world may have nothing to do with the story and would be distracting, so I disregard it.” He goes on to say: “In the case of Her we were facing one solid advancement (a highly intelligent OS with fast learning skills) and tiny other changes – the look of a different hand held device, some home automation, et cetera. I felt free to invent from scratch, what I thought best suits the story and engages the audience’s curiosity to imagine a world that is slightly different than ours.”

So it seems that perhaps Hollywood’s creative licence isn’t a reliable prediction for what’s to come, but the themes of industrial and muted minimalism have come from somewhere. Does art not imitate life? Or this truly a case of life imitating art? According to Barrett, we simply can’t keep up with ourselves. “I did a small amount of research on Sony, IBM, Google and their ideas of the future but found them unimaginative and short of what was already being shown in other sci-fi films or futuristic commercials. Clear glass devices? Holograms in daylight? The future seemed cold, or lacking tactile personality. In designing for film I try to clean the slate, dream from scratch, and go 180 degrees from anything that has already been hinted at. This is very freeing,” he explains.

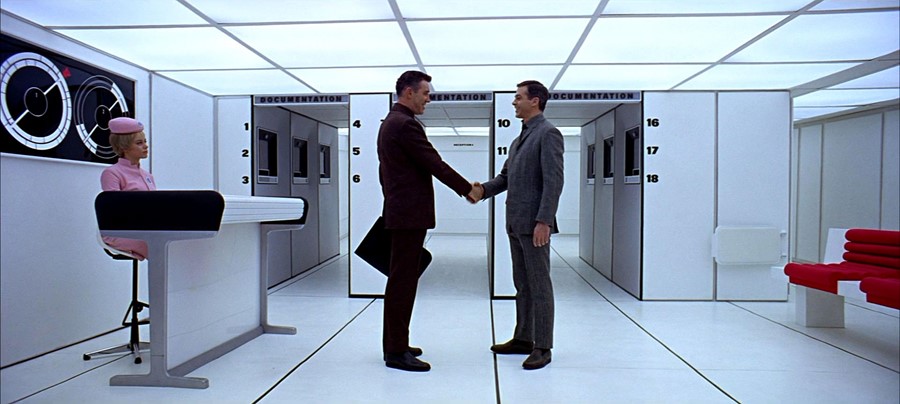

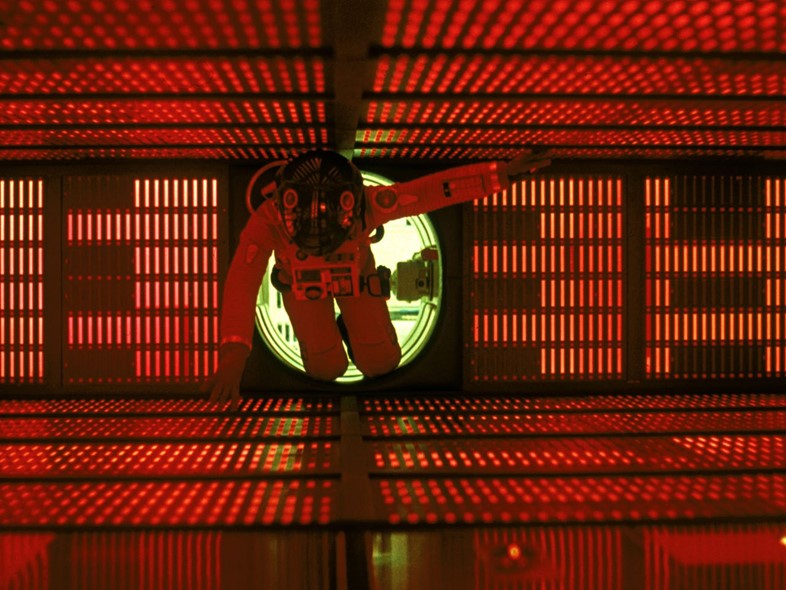

Perhaps the biggest lie we’ve been sold is that we will notice when AI takes over the world. Barrett argues that film has lulled us into a false sense of security, with us believing we are astute enough to notice when it all gets a bit too Skynet. “The usual way to bring attention to AI is to have it fail, run amok, threaten humans in its own AI interest. The best example is 2001: A Space Odyssey, from 1964. It did take care of reminders, operate a mission to keep the humans safe but didn’t trust them with the bigger picture. The real AI will be invisible and taken for granted, like most things are when they work well. We only complain when they don’t. So here is the problem of talking about AI. We won’t notice it if it truly helps us. Will we use the time regained wisely to be more human, or just watch more TV series?”