By subverting the classic summertime coming-of-age, Ava can see its realities so much clearer

In one scene from Léa Mysius’s film Ava, a young woman precariously feels her way across the roof of an apartment with a stick. She is blindfolded. “In a blindfold, it’s as if I vanish”, the voiceover says. It’s a line that speaks to a universal situation for girls coming of age, who feel the gaze of others so intensely. But when your sense of self totally relies on how other people see you, what happens when you can’t see them? Teenage girls, who are so constantly watched, are necessarily watchful. The twist, when it comes to Ava, is that our 13-year-old heroine is actually going blind.

Like a supernatural horror set in the suburbs, or a Bonnie and Clyde crime spree, the girl coming of age at a summertime resort is one of cinema’s most beloved – and hackneyed – tropes. There’s 17-year-old Baby shimmying her way into Patrick Swayze’s arms in Dirty Dancing, a film set in an unidentified holiday resort where all the staff are abnormally good dancers (“What they feel for eachother feels too good to be wrong!” the trailer proclaims gleefully). The premise of Grease is what happens after that summer, but still, everybody dances. In fact one glance at the kind of rom-coms aimed squarely at teenage girls will throw up any number of feel-good, female-centric, summertime-set bildungsromans.

By depicting coming of age, these are films that work on a very basic assumption: that the youth in question is a worthy subject because of their potential. It suggests a kind of coming-to-consciousness; being young once and, via some significant turn of events, becoming mentally older. When it comes to teenage girls, it problematically suggests there is a woman lying in wait within that girl (it’s not far from here to Lolita fantasy apologists). By summer’s end, the girl has “grown up”; her potential reached, or very clearly around the corner. Perhaps she has realised that her parents are real people, too; perhaps she has sought out popularity only to realise she was better off with her original, chubbier best friend; or perhaps, more often than not, she’s lost her virginity.

Mysius chooses to punish her central character with the curse of going blind. Hence, what Ava smartly presupposes is: what happens if that potential is cut short? And what, it follows, if those realisations never occur?

Ava, which premiered at Cannes last May and which launches on Mubi today, sees our teen protagonist (played by startlingly good newcomer Noée Abita, 17 at the time of filming) on a summer holiday with her hapless but neglectful mother (Laure Calamy) and newborn sister. Before we meet the fractious pair, the film opens with a classic landscape of garish holidaymakers at the beach; wonky striped umbrellas, bloated bodies, ice boxes, Martin Parr-sur-Mer. The sounds of children’s laughter and screeching rings in tune with the waves, before an aching, malevolent violin kicks in. You have to be eagle-eyed to notice at first; a huge black dog has disturbed the picture postcard scene, cutting through the shallow water like a wolf. Ava, lying asleep by the water, is woken up by the dog staring at her. That hulking dark shape foreshadows the black holes that will dominate the rest of Ava’s summer. As the doctor in the following scene informs her, soon Ava won’t be able to see in very low light, and next, she will go totally blind.

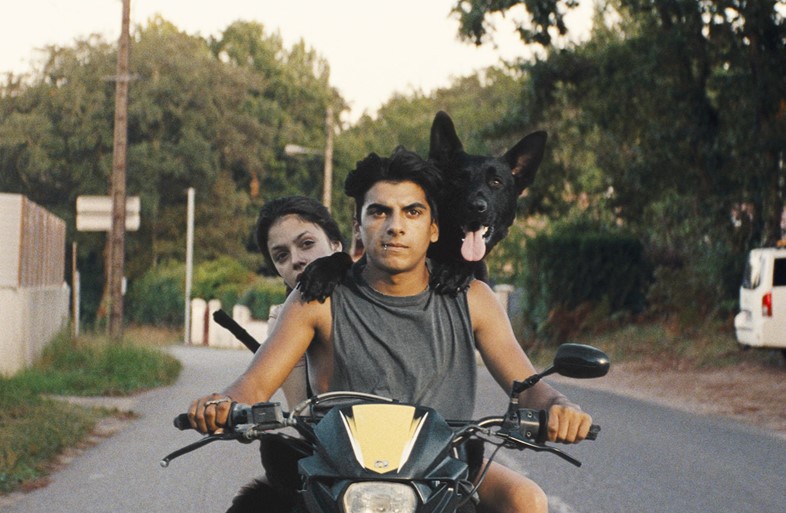

From the point of that diagnosis, Ava’s turn to the dark side quickens. She finds herself drawn to a punkish tearaway who appears to be sleeping rough, eventually losing her virginity to him and running away from home with him. While self-training to prepare herself for losing her sight, she sees a blonde child and throws rocks at her (“She was blonde and sunny, I am dark and invisible”). She’s plagued by graphic, terrible dreams. You might realise at one point that she hasn’t smiled for the entire movie.

When it comes to French films that take the summertime awakening of a young girl as their subject, Mysius has a playbook to follow. In The Lacemaker (1977), Isabelle Huppert’s debut role, she plays a young beautician who falls in love in a coastal resort only to have her heart broken by summer’s end. In most Eric Rohmer films going, bookish men resist the ‘temptresses’ who for the most part are oblivious, passive projections of their own fantasies. In a comic reversal of that trope, there’s also Mon pere, ce heros (1991), starring Gerard Depardieu. Perhaps it’s because French people tend to holiday on their own coasts, but a summer spent by the sea seems to send the sexual awakening of girl-heroines into self-reflexive hyperdrive.

True to its heritage, Ava wears its references on its sleeves, but prefers to skip the stereotypes. The best scene in the film might be the snap moment where Ava’s continually frustrated efforts to get closer to Juan suddenly cuts to a joyful montage of the pair of them playing at being bandits. The transition is in fact so fast that it feels like a dream-scene. Dressed as warriors, the duo run amok on the beach, chasing down nudist tourists with their BB guns and stealing the contents of their ice-boxes. It’s a clear throwback to Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek in Badlands (1973) or Jean Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina in Pierrot Le Fou (1965); on-screen odd couples with questionable morals who defy society together.

It’s telling that it’s only by putting characters in a difficult and harrowing situation – in Ava’s case, that of going blind – that a film can move beyond the stereotypical view of the purity and simplicity of the experience of coming-of-age for young women. While the realism falls off at points, and the ending seems a little evasive, this complicated film is so refreshing precisely because it refuses to expound the “clarity” of youth, and the supposed “clear-eyed innocence” of young women. Ava's vision is muddy, and so are her morals.

By telling Ava’s story, Mysius tells us that girls are not pure. They don’t live good-looking lives in good-looking places, like Luca Gudagnino’s privileged academics or, in a different but related way, Dirty Dancing’s Baby and all the tales that ‘babied’ its heroines after that. Instead, they come into contact with a world that would do them harm, and take their small revenge. It’s the image of Ava, naked and warrior-like, holding a gun to the camera, that speaks the most to the situation today’s young woman finds herself in: she’s exposed, she’s being watched, but she fights back.

For the imperfect girls among us, that’s practically life-affirming.

Ava is available to watch on Mubi from today.