New movie Loving Vincent offers a psychedelic trip into the startling and beautiful world of one of art’s most enigmatic figures

“We wanted to surprise people; to show them that there’s still something very new that you can see in the cinema, even now when there are so many films and TV series being produced all the time,” says Hugh Welchman, the co-director of Loving Vincent, an animated whydunnit centred on the death of Vincent van Gogh and told entirely in oil paint. The mesmerising film is comprised of 65,000 individual frames, which were hand-painted by a team of over 100 artists, using Van Gogh’s original artworks as reference points. They then worked from filmed scenes, acted out against a plain backdrop by a stellar cast including Douglas Booth, Saoirse Ronan and Jerome Flynn, the entire process taking six years to complete. Luckily the hard work paid off, and – just as Welchman and his wife and fellow director, the Polish artist Dorota Kobiela, had hoped – it makes for a viewing experience quite unlike any other.

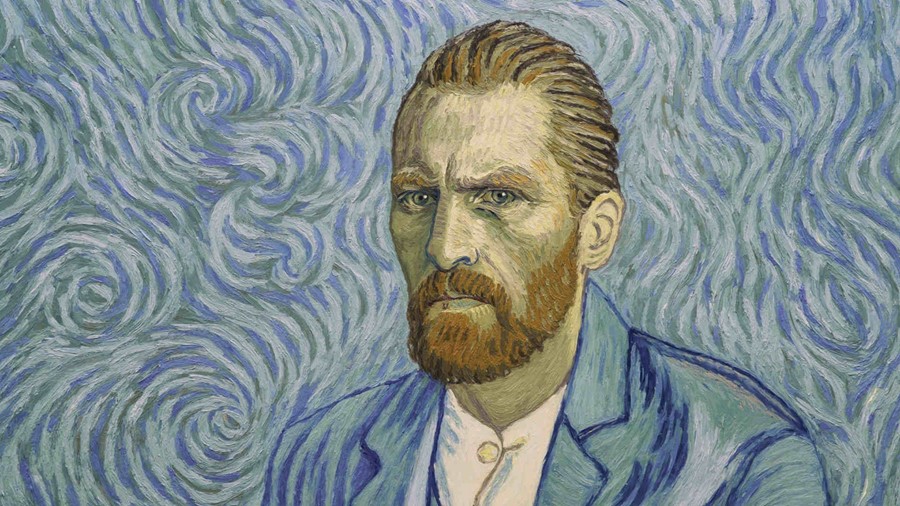

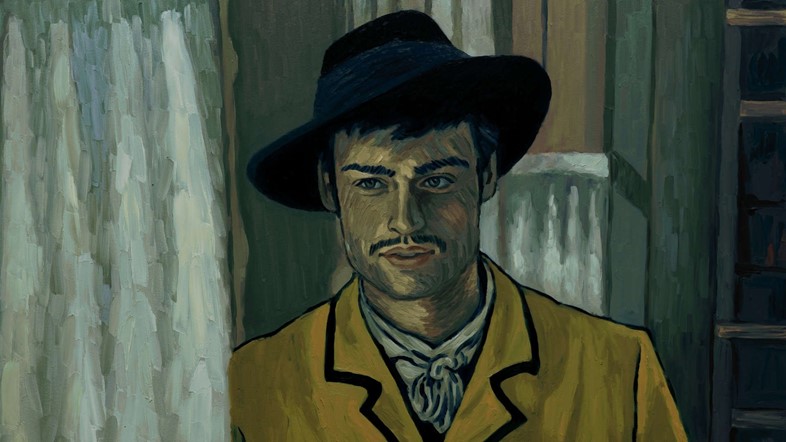

The film opens with Van Gogh’s masterpiece Starry Night, its spiralling strokes set in motion, dancing and swirling, sucking us into the scene and delivering us into the bustling streets of Arles. The effect is instantly, and enduringly, hypnotic. Soon we are introduced to our protagonist Armand Roulin (Booth). Armand was the son of Van Gogh’s close friend, the postman Joseph Roulin (here played by Chris O’Dowd) and was the subject of Van Gogh’s eponymous 1888 painting. Much like his portrait, Armand is presented as a sulky, somewhat cocky young man sent by his father, for the narrative purpose of the film, to deliver Van Gogh’s final letter to his brother Theo.

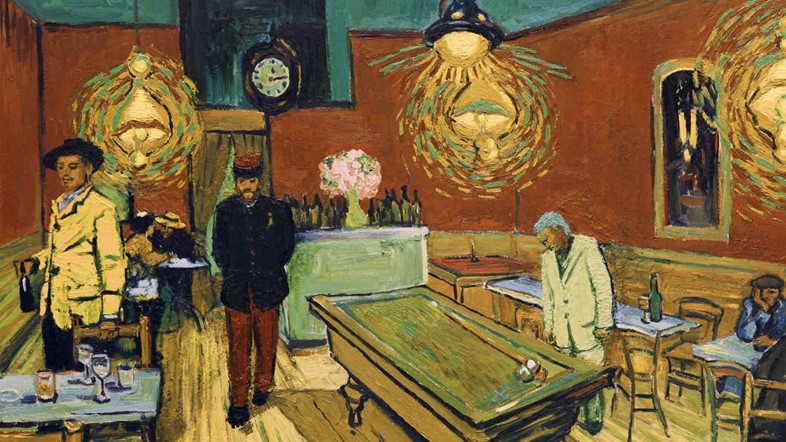

Armand’s mission leads him from Paris to the village of Auvers-sur-Oise in northern France, where van Gogh allegedly shot and killed himself some months earlier. There, his interest is unexpectedly piqued by the many mysteries enshrouding the artist’s death, and he makes it his mission to interview as many of Van Gogh’s acquaintances a possible – from Doctor Gachet (Jerome Flynn), the homeopathic practitioner who had been treating the painter’s depression, to Gachet’s daughter (Saoirse Ronan), his love interest, to Adeline Ravoux, the local innkeeper’s daughter – in an attempt to piece together what exactly happened in the days leading up to his death. We follow our amateur sleuth through scorched wheat fields and along picturesque riverbanks, from sumptuous interiors into sinister streets blackened by night, all rendered according to Van Gogh’s vivid brand of post-impressionism and interspersed every now and then by monochrome flashbacks to the painter’s past, with Polish actor Robert Gulaczyka in the role of the troubled genius.

“Dorota came up with the idea,” Welchman, who also runs his own production company BreakThru Films, best known for the Oscar-winning short Peter and the Wolf (2008), explains of the film’s conception. “She had been thinking about merging her love of painting with her love of animation and film for some time, and while re-reading Van Gogh’s letters, one of her favourite books, she realised that using his paintings to tell his story would be an amazing way of doing this. In the letter that was found on his body after his death, he said, ‘We can only speak by our paintings,’ which seemed to fit so perfectly.” The pair spent three years working out the film’s storyline. “It took us a long time to settle on Armand Roulin as the lead character,” says Welchman. “We included him as a cameo at first because it’s one of Vincent’s best portraits – you really get a sense of this good looking, edgy, slightly suspicious, proud boy – but he grew with each draft until we realised he was the perfect vehicle for the mystery direction the script was taking. Plus all we know about him is that he was a blacksmith’s apprentice and then at some point later in his life he became a gendarme, or rather an elite policeman, which just works so well with our storyline!”

Interestingly, because of true crime-esque formula of the script, Welchman and Kobiela found themselves looking more to investigative documentaries, like Carol Morley’s Dreams of a Life and Errol Morris’ The Thin Blue Line for inspiration, over animated features for inspiration, as well as “a lot of film noir,” Welchman adds. “We did think about Disney’s Snow White though,” he concedes, “which was all painstakingly hand-drawn and painted onto cels.” Loving Vincent’s realisation, on the other hand, involved the use of one canvas on which, Welchman explains, “a painter would create an artwork, based upon the reference material. Then, on that same canvas, they would repaint it to create movement – so all you’re seeing, for the first time, is photographs of oil paintings on canvas, which many find hard to believe!” So, what is Welchman and Kobiela’s overriding hope for their spellbinding movie, aside from breaking new ground? “I’d like to provoke or consolidate people’s interest in Vincent,” Welchman says with evident passion. “He was a very intriguing, inspiring and heroic human being and it’s great to play a small part in the incredible, ongoing story of his rise from obscurity at the time of his death to ruling the world as he does today.”

Loving Vincent is in UK cinemas from today.