Starring Richard E. Grant as an eccentric ad-man with a talking boil, How to Get Ahead in Advertising is an overlooked, and enduringly relevant gem

What if, after sloping off in the rain at the end of Withnail & I, Richard E Grant’s raging thespian had shelved his dreams of stardom for a six-figure job in advertising? That’s almost – but not quite – the premise of How to Get Ahead in Advertising, Bruce Robinson’s ill-fated follow-up to a beloved comedy classic.

In Robinson’s tale of two down-and-out actors propping up the bar as last orders is called on the 60s, Grant gave a star-making performance as the wretchedly funny Withnail. He’d been handed the script for Robinson’s next film, a nihilistic howl of rage at Thatcherite free-market philosophy, a week into the shoot, but a scheduling conflict saw the part offered to Daniel Day-Lewis, who had passed on Withnail just two years earlier.

“I was absolutely devastated,” recalls Grant, ahead of a double-bill screening of both films at Edinburgh International Film Festival. “I can’t remember precisely what happened, but I felt that the film’s producer, David Wimbury, had tried to shaft me. Then Daniel Day-Lewis turned it down, so I got to do it. When I finally did meet him three years later, on the set of The Age of Innocence, I literally prostrated myself in front of him in his Winnebago and said, ‘Oh Daniel, I am grateful to you for my two big breaks!’ and he said, ‘Arise, you’re forgiven.’”

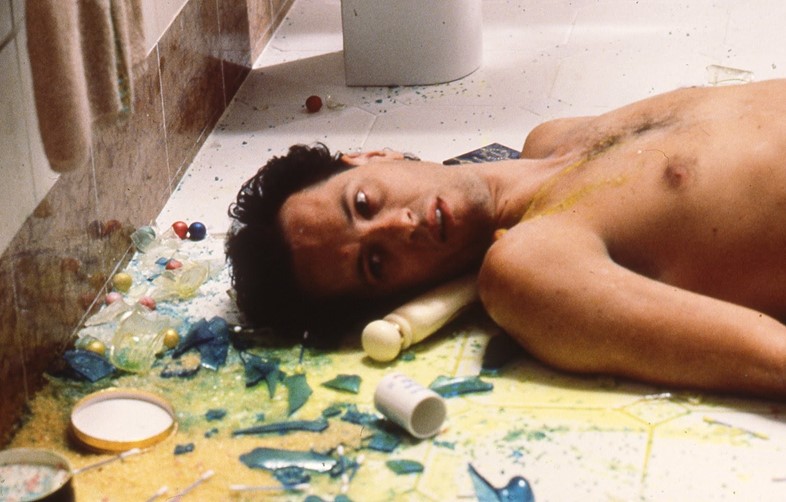

With all due respect to the three-time Oscar-winner, Day-Lewis’s loss was our gain – Grant’s performance as Denis Dimbleby-Bagley, a stressed-out ad-man who develops a talking boil, is every bit as tour de force as his Withnail. Bagley is a brilliant but vile character, a man for whom the world is “one magnificent fucking shop”. He suffers a sudden attack of conscience when he’s asked to come up with a campaign for a spot cream, and quits his job in the throes of a nervous breakdown (“I’m taking forever off!”). At this point, the film veers off into demented body-horror as he discovers a talking boil – voiced by Robinson himself – has appeared on his neck.

On paper, at least, Bagley is a million miles removed from Withnail. But certain traits – the monstrous ego, acid tongue and bottomless reserves of self-pity – make it tempting to see him as an older, even-less likable version of British cinema’s most iconic misanthrope. If Withnail & I portrayed the death of the 60s dream in a squalid little corner of London, How to Get Ahead is a film about what came next, culturally speaking – by extension, Bagley could be a disillusioned romantic à la Withnail, albeit one whose worldview has curdled further into cynicism. Did Grant see the characters as linked?

“I hadn’t really thought about it much, but I can definitely see the parallels,” he says. “They’ve both got their foot pressed firmly on the self-destruct pedal. They both have a mania about them, and also huge entitlement. [Like when] Bagley looks at that poor woman with a terrible boil on her face in the lift – he looks at her with the same disdain and disbelief and [feeling of] ‘How dare you!’ that is innate to Withnail.”

Grant remembers Robinson being drunk every day on the set of the film. “He had a bottle of Berola at lunchtime in Shepperton Studios so he basically had to sit down for the rest of the afternoon,” he says of his friend, an alcoholic who has repeatedly fallen off the wagon in recent years. “It was infuriating, but I’m smiling as I’m telling you this because he also demanded that I was in such a state of barely controlled hysteria and mania that, by the end of it, I was completely physically exhausted.”

How to Get Ahead in Advertising is a gibbering trainwreck of a movie, an overheated mess it’s impossible to tear your eyes from, thanks chiefly to Grant’s unhinged presence and a script laced with Robinson’s trademark venomous wit (“Perhaps if they’d hanged Jesus Christ we’d all be kneeling in front of a fucking gibbet!” exclaims Bagley to his wife, when she dares to question the ethics of his job). A flop on its release in 1989, the film all but buried Robinson’s career, and spelled the end for its studio, HandMade Films, whose closure in 1991 brought an era of subversive British filmmaking to a close. Grant, mortified by his performance at a rough-cut screening of the film, offered to return his salary to the director.

And yet, plenty of the film’s satire rings painfully true in 2017. Sometime around the 00s, after 9/11 bumped No Logo-style anticapitalism down the political agenda, we became resigned to the fact that ours was a world of advertising. But the industry’s power to shape the world has not diminished since the late 80s – it has increased exponentially, according to the insatiable logic that Bagley outlines to his therapist: “[Advertisers’ greed] won’t be satisfied, not till we’re squatting in one of its fucking hatchbacks on a motorway. But there isn’t going to be anywhere left to go, except in slow revolutions towards the crest of the next slag heap.” 30 years ago, marketing techniques were used to tell us what to spread on our toast of a morning. Now, they’re helping sway elections and peddle fake news.

It’s a sentiment that chimes with Grant, for whom “politics has become the new advertising”. “[How to Get Ahead] was an anti-Thatcher rant, and now we have Theresa May in charge of the Conservative party,” he says. “I can remember the feeling of political upheaval around Thatcher, but the chaos that seems to reign at the moment is even more than it was then, and my feeling is – it’s probably to do with my age – I think it’s created the exact environment for Donald Trump on the other side of the Atlantic to prevail, because we’re so used to soundbites and people promising things and then not making good on them that it’s very hard to believe anything they say. And that’s not confined to just one party, it’s all of them.”

Watching the film back now, the overwhelming sense is of a brilliant working partnership brought prematurely to an end. Grant’s natural fruity eloquence – a trait he credits to his upbringing in Swaziland, where the local English dialect harks back to the colonial era – feels tailor-made for Robinson’s dialogue, a kind of quintessentially English strain of gonzo. (“You look like a doomed bollock,” Bagley tells the boil at one point.) In an interview with Will Self a few years back, Robinson raised the tantalising possibility of directing two more films, an adaptation of his novel The Peculiar Memories of Thomas Penman, and The Block, a comedy about writer’s block. Could either of those pave the way for a reunion? Grant isn’t getting his hopes up.

“I remember Bruce telling me that I say his lines like they sound in his head when he’s writing them,” he says. “And I said, ‘Well why the fuck, then, have you not written and directed me in something subsequent to this?’ He said, ‘I will, I will!’ and I said, ‘Well, you’re 71 now, you’re gonna croak it in a couple of months the way you’re going.’ We have this battering-ram friendship, but I don’t think it’s going to happen now.”